By Mihnea Moldoveanu and Das Narayandas

Based on a 5 year study of the executive development industry, comprising interviews with over 200 executives, CLO’s, CEO’s, program designers and program developers, we have ascertained that the executive development field is at a critical crossroads, seeded by the digitalization of content and interactions and driven by the forces of disaggregation, decoupling and disintermediation that have already transformed the media, travel and entertainment fields:

• Payers (organizations) and users (executives) differ in most what they value in executive development programs, yet agree on the critical importance of skill development;

• There are large gaps between the skills required by most organizations and the skills executive development programs offer;

• There is widespread agreement that even when skills are acquired, they are not applied on the job – an insight that is backed by decades of research that points to the scarcity and difficulty of skill transfer;

• The Post-COVID executive development industry is currently being disaggregated, disintermediated and de-coupled in ways that increase transparency and offer incumbent and entrant providers alike significant opportunities for differentiation.

We offer CEO’s and CLO’s of both client and provider organizations a compass to navigating the new reality of their lives.

The executive development industry is at a critical stage in its development – accelerated and catalyzed by the restrictions imposed by the COVID pandemic. As in other industries such as telecom and media, the digitalization of content and interactions has unleashed forces disrupting the field via three mechanisms:

Disaggregation: Unbundling Content and Experiences

Education has always been a bundled good: as an executive, you would have to participate in a number of courses in finance, accounting, auditing, financial management just to obtain a certificate in ‘Mergers and Acquisitions’ from Famous Business School X. Often, these courses were offered by faculty members of different levels of talent, accomplishment and experience and could often be taken elsewhere at a fraction of the cost. But executives had to participate in them because they were part of the price of the chosen bundle. No longer: Massively distributed online learning systems deliver context– and setting-specific “skills on demand” in synchronous or asynchronous forms. They are packaged in free and fee-based configurations. State of the art platforms like EdX, Coursera, Udacity, LinkedInLearning, Udemy, Emeritus and 2U have amassed large repositories of leading edge content contributed by traditional suppliers of learning experiences like colleges and universities and leading practitioners – and organizations like BCG, Goldman Sachs, and McKinsey. The new Personal Learning Cloud enables a revolutionary change in the way skill development happens – unencumbered by the ‘filler courses’ that used to be ‘necessary’ fixtures of dated bundles, and informed by sharp signals of the quality of each instructor, regardless of institution.

Dis-intermediation: Freeing Up Content Creators

In an era in which content is quasi-free and learning management engines a commodity item, it is instructors – coaches, faculty members and senior consultants and advisors and executives with a calling for teaching – that are the scarce resource. And they know it: instructors are acting as free agents in the market for learning, offering courses on behalf of their parent institutions through platforms like Thinkific and capturing more of the value for their work. It is now the talented teachers and learning facilitators that are holding the ‘monopoly chips’. And they are easily discoverable by organizations’ talent development groups, which can quickly find the person teaching the best course on a desired subject.

De-coupling of the sources of value

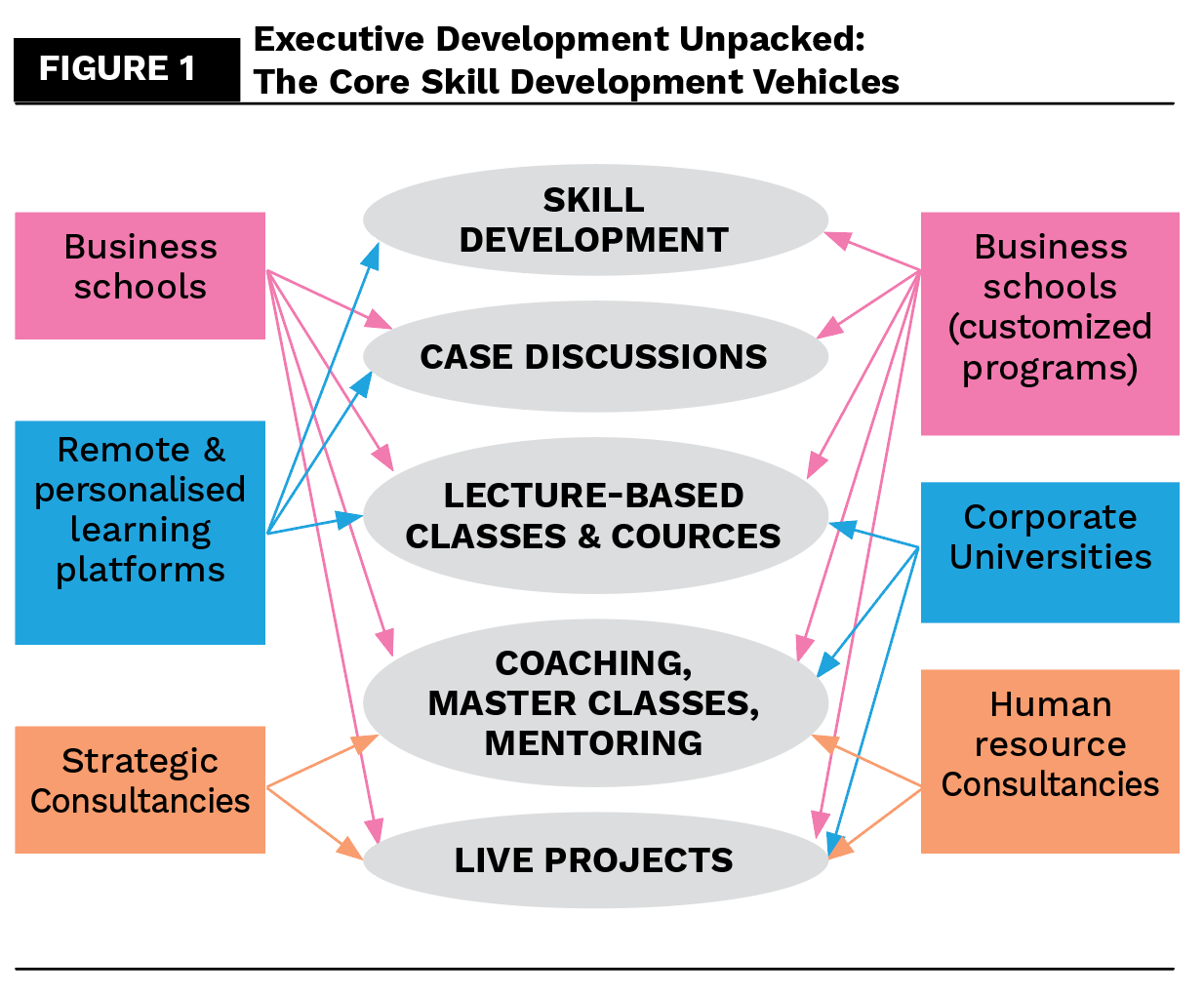

The value of executive programs goes way beyond content: ‘know-what’ is necessary but not sufficient to master the ‘know-how’ skills are made of. Know-how is built through experiences and interactions: different modes of discussion, interaction and assessment (Figure 1). Business schools, strategic and human resource consultancies, and corporate universities each uses one or more of the ‘standard blueprints’ for interactions that presumed to help executives skill up – be they simulations, case discussions, lectures, coaching sessions, or live projects featuring dense collaborative interactions.

Because data on the available options are more granular today than they were even 5 years ago, CLO’s and their CEO’s can now take a mix-and-match approach to designing the programs. They can de-couple a good lecture from a good discussion forum; a good facilitator from a good lecturer; and a great battery for testing a skill from a great set of practice sessions. The savvy CHRO can bring together the best of academic-created and practitioner-developed experiences and combine them to develop the skill sets her organization needs.

What do the Clients Want? The ‘new’ exec ed industry gives clients and their organizations broad option sets that can be empowering and productive. But choicefulness is only useful if one knows what one wants, which is why we focused our interviews and surveys on precisely what clients and payers want when they invest as much as they do in development. We found (Figure 2) organizations that pay for executive programs (to the level of almost 75% across industries) and participating executives have broadly different objectives and motivations:

• Executives often focus on expanding their social capital, developing their inner being and resourcefulness and signaling their quality and qualifications to the market via a set of credentials;

• Organizations that sponsor them typically value the enhancement of collaborative and communicative capital that accrues from people learning together, the concentration of learning-oriented activities in one specific program and location, and the cross pollinating effect of executives coming together in settings that allow them to explore commonalities.

But, executives and organizations come together in one objective: the development of skills (executives) and capabilities (organizations) that are new, applicable and valuable to the executive and the organization. The result is intuitive. Its evident appeal can be illustrated by a thought experiment: Suppose leading providers of executive learning programs discovered the skills and capabilities they teach, develop, nurture, or otherwise impart to participants lack the value they are widely perceived to possess, whether because the content is outdated, the means by which skills are developed is no longer suited to participants’ modes of learning, or the skills are not applied in the organizational contexts in which they provide value. Suppose that, upon discovering this, these leading providers modified their marketing message to convey only the networking and signaling value of their programs – a message that would go like this:

“Come spend time with us. You will build great new connections and get to signal the market that you have invested three weeks of your time and $40,000 to attend our program, in which you will get to know at least 30 other people who have made the same investment – or, at least, who work for organizations that have made it for them.”

Then the fine print might say:

“We know our content to be dated and methods of teaching and learning facilitation to be ineffective, but networking and certification are the most important deliverables of programs like ours. It is time to be realistic about what education is all about so do not ask for more and be grateful that we are truthful.”

Would you consider attending and paying to attend? Should you attend if admitted? The obvious answer is “no” to both – because of the absence of a credible promise of developing useful skills. Skill development is the basis of the selection and signaling value of such programs – along with the capability development sought by the organizations that invest in developing their executives’ skill sets.

To say something useful to the CEO’s of both client and provider organizations, then, we cannot but focus on skill development – which means we must first come to grips with the skills that are reliably associated with executive work. So, let us do that:

The Executive’s Skill Set: Unpacking the Black Box

A tectonic shift is afoot in the market for corporate control, as in many other labor markets. Call it the ‘skills revolution’. With know-what waning in importance and know-who increasingly volatile in a quickly changing social landscape, what increasingly matters is demonstrable know-how: the skillset an executive brings to her organization. Think of an executive as a bundle of skills: some technical, some cognitive, some relational, some emotional – not of degrees or credentials. And with the recent deployment of tools such as the LinkedIn Skills Graph, we can now figure out the skills bundle that is most valued for any position.

But, whereas degrees and certificates are easy to understand, skills are less so. At least right now. A skill is a demonstrated ability to complete particular tasks at a certain level of accuracy, reliability, and speed. It may be cognitive or non-cognitive in its nature and more or less relational and social in the way it is instantiated. We take skills to be learnable, and associate their development with structured programs of study, learning, training, and development. An executive role is best thought of as a bundle of skills – and, in order for an organization or a manager to figure out what skills she needs to develop, there must be a common reference, a set of skills that are useful enough to be desirable. But, unlike STEM skills, executive skills are elusive: we found that organizations, executives, academics and executive development program providers are challenged to articulate a core ‘executive skill set’ that contributes to organizations. Established research and databases on skills do not offer much help. Our interviews with executives and key decision makers in client organizations, however, revealed strong and nuanced intuitions about what executive skills are and are not, and about the key distinctions that need to be made:

Cognitive Skills

The skills associated with the standard models, methods, and languages of business that are operative in different functions of a company are both a set of representations (e.g. a model of an industry as a set of profit maximizing firms) and a set of methods (e.g., for inferring from a multivariate data set the effects of a new organizational effectiveness program relative to such programs in other companies and industries). Professional education courses, certificates, diplomas, and nano-, pico-, and femto-degrees proffered by distributed, online, and blended alternative business education that come with names like “Digital Marketing,”, “Financial Risk Management,” “Big Data Techniques for Database Design” – entail the sort of simple combination of know-what (models) and know-how (methods) characteristic of our “cognitive skills” category.

Meta-Cognitive Skills

Chester Barnard’s Functions of the Executive (1938) was among the first signs of growing awareness that leadership, high-level management, and the exercise of an executive’s functions rely on a set of skills that lie beyond functional expertise. There is a difference of kind and quality between solving a classifier algorithm design problem in an artificial intelligence lab and leading a group of AI researchers with different theoretical and cultural backgrounds charged with developing a beta-ready release of an app that translates spoken Mandarin to written English in real time to success in three quarters. Such distinctions help us tease out the “higher level” skills executives exercise to build new models that integrate across disciplines, and define and structure problems in ways that are agreeable to multiple stakeholders. The significance of these skills receives support from studies like IBM’s Global Chief Executive Officer survey, which concluded from the input of the 1,500 CEOs who participated that “rapid escalation of complexity is the biggest challenge confronting [the world’s public and private sector leaders]” (Palmisano, 2013), which found that more than half of those surveyed doubted their ability to manage the anticipated rise in the complexity of the chief executive’s predicament: Managing the complexity of business predicaments emerges as a core characteristic of more successful executives and organizations.

Affective and perceptual skills

We can characterize the emotionally intelligent executive as being better at making reliably valid inferences about others’ intentions from observations of their verbal and non-verbal behavior (empathic accuracy), changing affective states and moods in response to the context, content, and constraints of a situation (e.g., “being angry at the right person at the right time for the right reason in the right way”), and exhibiting openness to understanding and validating alternative and often opposing emotional commitments and attitudes. Heart and mind must work together to make progress in solving problems that involve the hearts and minds of others, whose perspectives can lead to a better solution even if they are in tension with one another.

X-skills: Self-command, self-control, self-regulation

The tightest formulation of the “executive functions of the brain” is provided by Donald Stuss’ (2011) work on the clinical management of neurodegenerative conditions (Alzheimer’s, dementia) distinguishes among functions of the frontal lobes of the brain that have to do with the energization of different tasks and subtasks (do-THIS-now), partitioning of large problems into manageable tasks and objectives and allocation of tasks and objectives to different, sub-problems (do-THIS-first), and suppression of temptation and unconstructive impulses when engaging in a wide array of tasks (do-THAT-not-THIS). Self-awareness is also a relevant executive skill rather than attribute or characteristic, particularly in view of recent discoveries of its relationship to an interoceptive function of the mind-brain that enables an individual to accurately answer questions like “How am I feeling now?” We term the self-awareness-self-command-self-control-self-regulation nexus X-skills. However self-evident to executives and their coaches, the X-skill nexus has not been included in the executive skill set that is explicitly developed or even selected for by executive program providers.

Individual versus relational skills

To get clear about relational skills we interviewed several high ranking executives and participants in executive programs, reflected on our experiences as executives, and conducted group discussions aiming to get clear about the skills involved in that most paradigmatic of executive activities – running ameeting, which is a pointer to a complicated process that includes setting it up, introducing and motivating it, having everyone around the table or the Zoom or Google Hangout screen feel empowered to speak his or her mind, in ways undiminished by ritual and free from coercion, have everyone at the same time feel and think that progress has been made, that words matter and commitments count, and that reasons as well as feelings will be heeded and addressed in a timely and forthright and authentic fashion. Given that a skill is an observed propensity to complete a task in a certain amount of time at a certain level of quality and a certain reliability, we asked ourselves and our interlocutors to articulate the tasks which, if successfully completed, often jointly lead to the kind of high-integrity, effective, open and responsive interpersonal experience that most teams wish for and very few if any achieve in their get-togethers. Here they are:

• Tuning in to someone in a way that makes it clear to them they are being listened to and heard;

• Sensing the emotionality, mood, expression of another person and giving clear signs to her that the fullness of her presence is heeded and felt;

• Paraphrasing accurately the statements of others around the table, in ways that get them to feel their points of view, claims, sentiments, reasons, arguments, questions, challenges and concerns have been understood;

• Reacting in ways that are clearly visible to others around the table (or the Microsoft Teams screen) to demagogical, needlessly aggressive, deceitful or subversive moves and manoeuvres made by others;

• Responding to questions, challenges, concerns – as well as to perceived sentiments and moods – of participants, in ways that make it clear to them their contributions and actions count, and that they are understood;

• Energizing (de-energizing) discussions – by changing tone, loudness, body language, choice of words – in order to accelerate (decelerate) or amplify (attenuate) particular moments in a meeting;

• Articulating claims, reasons and the arguments for them in ways that create agreement among participants regarding the facts, principles that are necessary for the discussion to proceed;

• Deconstructing claims, arguments and reasons put forth by others to make explicit those assumptions that would benefit from public questioning and deliberation.

‘How Will You Develop Them?’

Executive program designers need to understand not only the skills maps and gaps that characterize and beset an organization, but also how and when and how well skills acquired are applied. To yield a return on investment, new skills must not only be acquired but also applied in the context of the organization that invests in their development. Skill development thus needs to satisfy the following simple equation:

To be effective, executive programs must address both elements of the right-hand side of this equation: participants should acquire new and useful skills that should transfer – or, apply – to the work they do within their organizations.

Skill Acquisition

Just as we illuminated the nature of useful executive skills using a few distinctions, we make sense of how such skills are acquired by another pair of distinctions.

Algorithmic skills versus non-algorithmic skills

The first distinction is that between algorithmic and non-algorithmic skills (Moldoveanu and Martin, 2008):

• If a skill is the ability to perform a task whose execution can be written as an algorithm, that is, a step-by-step procedure like a recipe or computer program, the skill is algorithmic. Examples include basic calculations of ROI and NPV in finance and accounting; or equilibrium calculations in the microeconomics of consumer behavior; or the computation of Nash Equilibria in a non-cooperative game; or figuring out the optimal configuration for a COVID vaccine supply chain in countries that lack vaccine manufacturing capacity – like Canada.

• Other tasks do not admit of an algorithmic description – such as “creating a welcoming, open communication environment,” “conceptualizing a predicament that is acceptable to multiple parties initially at odds,” and “credibly and publicly taking responsibility for an error”, or “authentically and truthfully validating your strongest critic in a board meeting”. Most algorithmic skills are cognitive – but not all cognitive skills are algorithmic. And while many perceptual and affective skills (eg. empathic accuracy) seem difficult to characterize in algorithmic terms, some affective skills (e.g., altering breathing patterns in predictable ways to quiet the mind to the point where severe ambiguity can be contemplated without a rise of more than 10% in heart rate) are algorithmic in nature.

Algorithmic skills are more readily “digitalized” and made amenable to online, distributed instruction that follows the basic schema (See-Do-Repeat):

• see it done in detailed step by step sequence,

• try to do it (with step-by-step feedback), do it yourself (with feedback on outcome and output);

• repeat the attempt and measure improvement from one iteration to the next.

The development of non-algorithmic skills often requires intense, textured, and subtle feedback and constant dialogue between learner and learning facilitator that can change the nature of the learner’s objective function ‘on the fly’. “Presence” in interpersonal communications and “attunement” to the emotional states of others are usually viewed as leadership skills best developed in the context of a coaching relationship that features frequent, accurate feedback. Coaches routinely employ a “method”; but no coach can specify an algorithm for getting to presence or attunement, because their methods are not algorithms, but heuristics, prompts, nudges and principles whose application is sensitively dependent on the who, what and how of context.

Always-teachable skills versus only-learnable skills

Not all skills are teachable; and, while it may be that not all skills are learnable, there are skills that are learnable but not teachable. It is important to distinguish between skills than can be taught and learned and skills that can only be learned, sometimes with facilitation and feedback, but never via specific codified instruction. Riding a bicycle is a classic example of an important and valuable skill that cannot be taught by having the uninitiated owner read a manual or set of instructions or pursue a degree in classical mechanics. Competence at this skill is built through a delicate interplay of perception (gaze control, feedback/feed-forward balance signals), movement (arms, legs, torso, hips), and predictive processes (‘slope coming’) that produce synchrony and synergy among several sensory and motor control functions. The skill is best and most successfully taught to eager children by loving, attentive parents or friends who rely on frequent demonstration and feedback. Similarly, “giving effective face-to-face negative feedback” cannot be “taught” using a set of explicit step by step methods, but it can be learned under the patient guidance of a savvy master trainer able to guide the learner to a “better approach”. “Better” means not only “more informative or sensitive” but also possessing greater fit with the learner’s “way of being.”

The algorithmic/non-algorithmic and always teachable/only-learnable distinctions illuminate the process of skill acquisition explain to a considerable extent the dynamics of the executive program industry. Diverting acquisition of algorithmic skills, especially of the sort that are always teachable, to the digital cloud frees the face-to-face and in-person classroom medium to specialize in the more intensive and costly cultivation of non-algorithmic skills, especially the sort that are not teachable.

Skill Transfer

Executives and organizations alike are dismayed at the low frequency with which skills developed inside and outside of the classroom are applied to the tasks executives perform in their organizations: Skill acquisition is no guarantee of skill application. Far from it. The 100+ year-large literature on skill development is equally pessimistic about skill transfer, about skills acquired in the classroom being transferred or applied to the tasks for which the skills were learned to begin with. By some reckonings, only 10% of the $200Bn/year spent on corporate training in the US actually lead to a net improvement in the skills that were advertised as being developed by providers, a very large negative NPV on a massive investment made by organizations in up-skilling.

That this enormous skill transfer gap has not been sensed and signaled in our industry is not surprising, given the kind of feedback program providers solicit from participating executives. It relates largely to participants’ enjoyment and subjective estimates of use value – which happens to correlate very highly with enjoyment. Curiously, few organizations are polled, independently, by providers, about the value of a training program to its executives and the organization as a whole – which would likely uncover the gap between skills promised to participants by providers, and skills applied on the job and converted into organizational capabilities.

But, skill transfer in the executive development field is not nil. It happens. Infrequently, with difficulty, in some programs, some of the time. But we do not know when, where, and with whom. Fortunately, with CEO’s, CLO’s and CHRO’s making ‘buy’ decisions for executive development programs can now take full advantage of a digitalized executive learning environment that has lowered search cost and made feedback and measurement easier, cheaper and potentially more accurate than it has ever been. They can insist on a level of disclosure, feedback and verification that can quickly reveal the degree to which the skills promised by program providers are in fact used by participating executives, upon completion of a program.

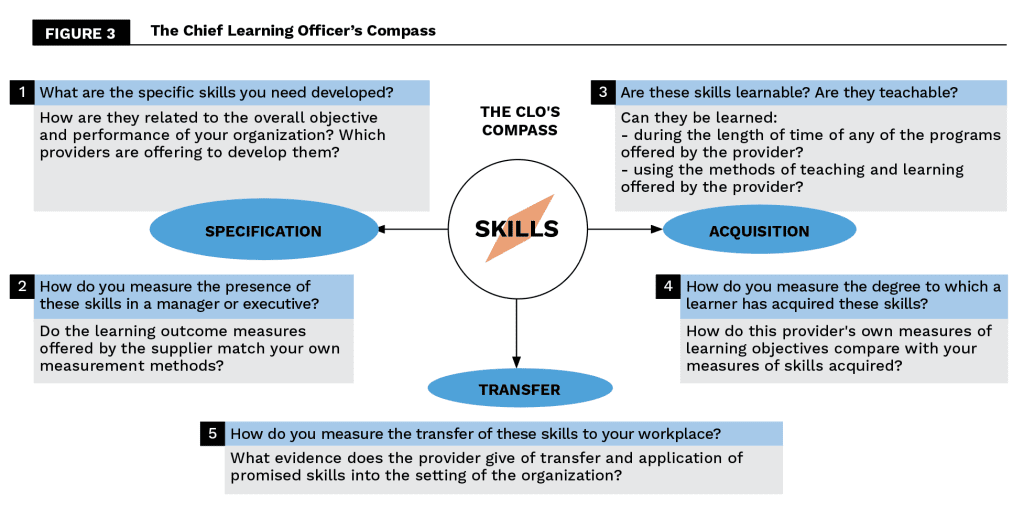

The Chief Learning Officer’s Compass

We have entered a new landscape in the field of executive development. The three ‘demons of digitalization’ – namely disaggregation, disintermediation and decoupling of the sources of value have been fanned by the post-COVID remote learning environment and are delivering more choice and opportunity to succeed – but also to fail – than ever before. A re-conceptualization of the field as a whole as a skill development enterprise, rather than one devoted to acquiring subject matter expertise, has turned the standard operating model of executive education providers upside down, and in many cases has fogged up the dashboards of Chief Learning Officers searching for development opportunities. The industry needs a new compass – a battery of critical questions an executive development experience buyer should answer before investing in an executive development program:

First, to contract with programs that shall help their executives develop useful skills, organizations have to specify these skills precisely. If you do not know where you wish to go, it does not matter what direction you take’. Just so, if a Chief Learning Officer cannot define the skills his or her executives need, it will not matter which provider or program he or she turns to. However, just as understanding machine learning is more than learning how to rattle off a few terms and names, learning and using a skill is much more than knowing a topic. To specify the skills their companies need, CLOs must look under the ‘subject hood’ of course offerings: beyond ‘topics’, to the skills instructors claim to help participants learn. But the task is not easy: Courses and learning experiences are described in terms of subjects and knowledge areas (‘financial accounting’, ‘Blockchain for financial services’, etc – forming what we call the ‘subject hood’) – which makes them opaque regarding the skills (eg.: ‘programming simple contracts in Ethereum and iOS; creating pro forma income statements and balance sheets in Excel’) that participants can hope to acquire and bring back with them. It is not enough for a CLO to ask: What new terms of art will our executives learn by participating in the program?, or, what new frameworks will they contribute to the conversational capital of the organization? The question CLOs should ask is rather: What do we need our executives to learn to do and will they learn that in this program? – and select programs on the basis of useful skill demonstrably developed – and not by ‘topic covered’. Thinking of an executive as a bundle of skills – rather than as a repository of domain-specific knowledge with certain traits, proclivities, and educational background – allows CLOs to figure out the skillset associated with role, and the relative value of different skills for that role.

The other end of the compass’ needle helps CLOs become more precise about the ways in which a program will help participants acquire the skills that the organization deems are important.

• Are those skills teachable?

• Are they teachable by standard methods such as lectures, discussions and quizzes?

• Are they learnable though guided practice and feedback even if they are not teachable by standard methods?

Importantly, skill acquisition measures must help CLOs distinguish between programs that have, and haven’t, enabled skill acquisition. Pre– and post-program skill-measurements must be conducted: CLOs should measure skill development in participants not only before every program, but also, after they return after completing them, to answer:

• What has changed?

• How has it changed?

• Is there evidence of the application of the skill after attending the program

• Is there data suggesting individual skills acquired have turned into organizational capabilities?

A Compass for Program Providers

Providers experience disaggregration, disintermediation and decoupling as significant and sometimes discouraging challenges. Education providers that want to cope with the current disruption of the executive education industry must re-think what it means to skill up executives – from first principles. That means understanding what an executive development program is about at its core. To help do so, we decomposed an executive education program into two different components, the context of learning – and its content.

Context –

the cultural, geographic, and organizational factors that shape learning outcomes – is critical to addressing the skills transfer gap: the very large chasm between skills that are acquired and skills that are applied on the job. Learning management engines, and personalized learning platforms have made mere information (data and facts) free to all users.

So, the content of learning must also be re-designed. Providers that hope to persuade organizations to sign on as payers and executives to leave their work and families for long periods to attend on-campus programs need to design programs that justify large investments of time and money because they are more valuable than any experience that can be remotely replicated – especially in the post-2020 age when no executive feels uncomfortable in remote discussion or collaboration settings. In grappling with the challenge of a new landscape, providers could also use a compass:

Content-related questions relate to the thematic and topical subject matter presented and discussed in a program including case studies, notes, visual materials, and online materials. Among the issues:

• What are the skills the content is designed to cultivate? Are they primarily cognitive and technical in nature, or, rather, emotional and relational?

• How does the content help cultivate those skills? What is the relationship between the content and the skills that the content is meant to inculcate?

• How is the content designed to maximize skill acquisition by participants? What are the specific prompts that get executives to exercise the skills that the program is designed to build?

• How does it maximize skill transfer to work related tasks? What are the specific instances in which the skills developed in the program are used on the job?

Context-related questions relate to the times and places of interactions among learners; their interactions with facilitators; the relationship between the program content and the participants’ skills and predispositions; and their work experience. To wit:

• How is the program’s context designed to maximize skill acquisition? What are the activities that require executives to exercise the skills that organizations value most?

• How is the context designed to maximize the transfer of skills to work contexts? How are the tasks of the executive development experience meant to get executives to see the connection and feel the connection between what they learn in executive development programs and their work related tasks?

• To what other contexts can these skills be transferred? How is the teaching material designed to maximize the probability that what is learned is actually applied, to contexts relevant to the organization?

Few education providers seem to understand the kinds of skills client organizations need – or the best ways of developing them – or that the language and associated practices of ‘subjects’ and ‘subject matter experts’ needs to be replaced by a language of ‘skills developed’ and ‘learning facilitators’ in even thinking about what they do. It is time they started.

The article is based on a large-scale study of executive development undertaken while the authors were both deans in charge of the executive development organizations of their institutions. They are are co-authors of The Future of Executive Development (Stanford University Press, 2022).

About the Authors

Mihnea Moldoveanu is Desautels Professor of Integrative Thinking, Professor of Economic Analysis and Director of the Desautels Centre for Integrative Thinking at the Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto, where he is also Founder and Director of RotmanDigital, the Self Development Laboratory, the Leadership Development Laboratory and the Mind Brain Behavior Institute.

Mihnea Moldoveanu is Desautels Professor of Integrative Thinking, Professor of Economic Analysis and Director of the Desautels Centre for Integrative Thinking at the Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto, where he is also Founder and Director of RotmanDigital, the Self Development Laboratory, the Leadership Development Laboratory and the Mind Brain Behavior Institute.

Das Narayandas is Edsel Bryant Ford Professor of Business Administration and Senior Associate Dean of HBS Publishing.

Das Narayandas is Edsel Bryant Ford Professor of Business Administration and Senior Associate Dean of HBS Publishing.