By Moritz Hahn and Niccolò Pisani

Online retailing is clearly on the rise. In this article the authors offer a snapshot of the current status of online retailing and provide insights on how differences between countries play a fundamental role in shaping firms’ internationalisation in the online space.

Pure-play online retailers have, at least in principle, an unlimited trading space that spans beyond the borders of the country where they are headquartered. Webpages and mobile applications can be accessed from anywhere in the world, orders processed online, and products efficiently shipped across national boundaries. To internationalise the operations of pure-play online retailers may appear relatively easier when compared with traditional companies, as there is no need to rely on investments in brick-and-mortar retail spaces in foreign countries to attract local customers. Yet, to expand abroad in the online space is as difficult as in more traditional marketplaces. In this article we aim to offer a snapshot of the current status of online retailing and provide some insights on how differences between countries play a fundamental role in shaping firms’ internationalisation in the online space. In particular, we focus on the apparel and footwear online market and the case of Zalando, the largest pure-play online fashion retailer based in Europe.

Online retailing is clearly on the rise. This pattern is recognisable across all world regions. Despite a recent impressive growth observed in Asia, the North American and European markets still report the largest online retail sales figures.1 In 2013 online retailing reached $262 billion in the US – a growth of 13% over 2012’s $231 billion.2 In Europe it peaked at €142 billion – a rise of 16% over €122 billion reported in 2012.3 Albeit this remarkable annual growth rate (steadily maintained over the 2009-2013 period), the web penetration is still relatively limited in the retail market. The above-mentioned 2013 figures correspond in fact to respectively 7% of the total retail value in the US and 5% in Europe. Other regions report an even lower level of online penetration in the retail industry (4% in Asia-Pacific and 2% in Latin America), suggesting that we are still in the early days in terms of adoption of this new channel.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]While many products are sold online, three categories are most relevant: the so-called fashion market (whose three main product classes are apparel, footwear, and accessories), consumer electronics, and computer hardware.4 In 2013 the total sales value of the apparel and footwear online retailing market (which accounts for about 85% of the total fashion market) was $37.3 billion in the US ($20.6 billion in 2008) and €29 billion in Europe (€15 billion in 2008). In Europe this corresponded to approximately 20% of all online retailing and 7% of the total fashion market.5 Not surprisingly, companies like Amazon have taken fashion very seriously in the last few years, recognising the untapped potential of this market in the online environment.6

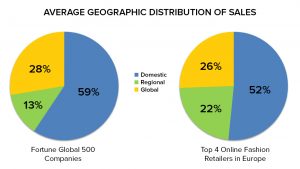

Given this strong and steady growth, the question arises whether online fashion retailers are expanding abroad more aggressively than traditional companies in order to benefit from this trend across countries. To grasp the extent to which online fashion players are international today we collected publicly available information relative to the geographic distribution of sales of the 4 largest online fashion retailers in Europe (i.e., Otto Group, Amazon, Zalando, and eBay) and compared it with the average internationalisation degree of the world’s largest corporations included in the 2014 Fortune Global 500 (FG500) list.7 The results of our analysis suggest that online retailers don’t behave very differently from traditional companies when expanding abroad (see figure below).

The study that one of us (Pisani) recently undertook with Prof. Pankaj Ghemawat, a leading expert on globalisation, showed that companies listed in the 2014 FG500 have a clear propensity to locate the bulk of their activities at home.8 The results of our comparison reveal that such bias is maintained among the largest online fashion retailers. While they show a relatively greater internationalisation degree than FG500 companies, they have an almost equivalent predisposition when it comes to expand beyond the home region. Thus, the online space hasn’t really revolutionised companies’ international paths. Why is it so? One may think that the reliance on the online channel would facilitate foreign expansion. However, our findings indicate that even the largest online players tend to be as dependent on home revenues as more traditional companies.

The reality is that distance between countries still matters, not only in traditional brick-and-mortar markets but also in the online environment. Countries differ among themselves and this creates additional challenges for internationalising companies. Failure to evaluate the impact of cross-country distance can jeopardise firms’ foreign expansion. This equally applies to pure-play online retailers. To illustrate this notion, we focus on the case of Zalando, the largest pure-play online fashion retailer based in Europe. In the last 5 years Zalando has expanded its operations to 15 European countries and its webpage is currently the most visited fashion website in the western world, with a monthly average of 21 million unique visitors.9 The foreign expansion undertaken by Zalando provides insightful examples on the importance of a careful appraisal of cross-country distance for the international success of pure-play online retailers. Building on the CAGE framework introduced by Prof. Ghemawat to evaluate differences between countries, distance can manifest itself along four basic dimensions: cultural, administrative, geographic, and economic.10 In the following paragraphs we will briefly describe each of the dimensions and provide examples of their relevance based on Zalando’s experience.

The reality is that distance between countries still matters, not only in traditional brick-and-mortar markets but also in the online environment. Countries differ among themselves and this creates additional challenges for internationalising companies. Failure to evaluate the impact of cross-country distance can jeopardise firms’ foreign expansion. This equally applies to pure-play online retailers. To illustrate this notion, we focus on the case of Zalando, the largest pure-play online fashion retailer based in Europe. In the last 5 years Zalando has expanded its operations to 15 European countries and its webpage is currently the most visited fashion website in the western world, with a monthly average of 21 million unique visitors.9 The foreign expansion undertaken by Zalando provides insightful examples on the importance of a careful appraisal of cross-country distance for the international success of pure-play online retailers. Building on the CAGE framework introduced by Prof. Ghemawat to evaluate differences between countries, distance can manifest itself along four basic dimensions: cultural, administrative, geographic, and economic.10 In the following paragraphs we will briefly describe each of the dimensions and provide examples of their relevance based on Zalando’s experience.

Cultural Distance. Differences in languages, religious beliefs, ethnicities, and social norms create cultural distance between two countries. While language differences are easily identifiable, dissimilarities in social norms – the customary rules that govern behaviour in a country – can be extremely difficult to grasp. One could argue that social norms are relatively similar within Europe, especially vis-à-vis the US. Yet, patterns of behaviour are significantly different across European countries. Failure to recognise and appropriately respond to such local nuances can compromise online players’ international success.

At a first glance paying methods in online retailing appear relatively standardised, with major credit cards (e.g., Visa) and online payment systems (e.g., PayPal) being the most commonly adopted methods. This said, widely accepted norms associated with monetary transactions can radically differ across countries, even within Europe. In Italy for example there is a strong propensity to use cash to settle payments. When Zalando first entered the Italian online retailing space, it offered the possibility to choose among the most popular online payment methods, but not cash-on-delivery. Still, the conversion rate – customer orders divided by unique customer checkout visits – was substantially lower compared with other major European markets. In August 2011, Zalando introduced the possibility to pay cash-on-delivery for Italian customers. In the two weeks following the introduction of this new payment method the conversion rate increased by nearly 25% and the higher rate achieved has been maintained ever since.

Administrative Distance. The administrative or political distance can result from the usage of different currencies, the adoption of distinct policies to regulate commercial activities, or the reliance upon dissimilar political frameworks. In general, absence of trade arrangements between two countries amplifies their administrative distance. While the establishment of the European Union can be regarded as a major effort to minimise this type of distance between member countries, online retailers still need to account for a variety of administrative issues when crossing borders within Europe.

For instance, conventional wisdom would suggest that Germany and Austria are rather similar markets from an administrative point of view, especially for an online retailer. However, Zalando’s experience proves that there exist several differences when operating in the online space of these two countries. In Germany for example it is necessary to adopt a double opt-in procedure when asking customers for their consent to receive a newsletter, while in Austria a single opt-in procedure is sufficient. This means that German customers need to tick a previously un-ticked checkbox and then also click on a confirmation link received via email before they can receive any promotional material whereas Austrian clients need to formalise their permission only once. This difference has obvious implications for marketing strategies, as the use of tailored newsletters cannot be equally adopted across markets.

Geographic Distance. The physical distance between home and host country, the lack of a common border and differences in climate, size, and topography contribute to the emergence of geographic distance. Climate for example has a major role in determining what people shop, especially in relation to the apparel and footwear market. This creates the need for a locally adapted product portfolio and equally applies to brick-and-mortar and pure-play online players. Differences in the topography also matter, for instance in relation to the selection of logistic partners for product deliveries. While global providers can guarantee presence in all countries and count on superior scale economies, local providers rely on deeper roots in the territory and this at times turns into a more capillary coverage of isolated provinces. To this end, Zalando has 11 local logistic partners in order to secure a timely delivery of products across all 15 European countries served.

Economic Distance. Variation in consumer incomes is the most relevant factor contributing to the creation of economic distance. Countries differ in their wealth per capita and this has obvious consequences on consumers’ choices and purchasing habits. Pure-play online retailers need to consider such local idiosyncrasies as they heavily influence how to succeed in a country.

In the context of the online fashion market, the cross-country analysis of Zalando consumers’ buying patterns suggests a positive relationship between the average net basket size (calculation is made at the net of returned articles) and the GDP per capita of the country where the consumer is located. Net basket sizes therefore tend to be smaller in Spain and Italy than in Germany and even smaller than in Sweden and Norway. This has major implications for Zalando and the way it competes across Europe. Marketing expenditures have to be adjusted as the average customer shops significantly less in certain countries. Discounts and promotions need to be tailored to local consumers’ purchasing habits and thus reflect cross-country economic distance between countries.

Distance between countries still exists and continues to matter. Pure-play online retailers need to carefully consider cross-country distance when internationalising their activities. The online space hasn’t converted the world into a homogenous space. Failure to recognise differences between countries can lead online retailers to major mistakes, even when conventional wisdom suggests that home and host country are similar. Recent research shows that online shopping hasn’t also homogenised consumers’ needs.11 Customers continue to make online purchases based on where they interact offline rather than on what they see online. This further enhances the influence of the local environment in online competition. Thus, the accurate evaluation of all dimensions associated with cross-country distance is not a superfluous exercise for pure-play online retailers; it is rather their only route to international success.

About the Authors

Moritz Hahn is Senior Vice President at Zalando SE, where he leads all markets across all categories. Prior to joining Zalando SE he worked for over 6 years at McKinsey & Company. He holds a Ph.D. in Economics from Ludwig-Maximilians Universität München. During his Ph.D., he was visiting scholar at the European Central Bank as well as New York University. His research has appeared in peer-reviewed journals as Review of Financial Studies.

Moritz Hahn is Senior Vice President at Zalando SE, where he leads all markets across all categories. Prior to joining Zalando SE he worked for over 6 years at McKinsey & Company. He holds a Ph.D. in Economics from Ludwig-Maximilians Universität München. During his Ph.D., he was visiting scholar at the European Central Bank as well as New York University. His research has appeared in peer-reviewed journals as Review of Financial Studies.

Niccolò Pisani is Assistant Professor of International Management at the University of Amsterdam. He holds a Ph.D. in Management from IESE Business School. His research is mainly focused on the international strategies of multinational enterprises. He regularly presents his studies in leading international conferences and his research has appeared in peer-reviewed journals as Journal of Management and practitioner-oriented outlets as Harvard Deusto Business Review and the digital edition of Harvard Business Review.

Niccolò Pisani is Assistant Professor of International Management at the University of Amsterdam. He holds a Ph.D. in Management from IESE Business School. His research is mainly focused on the international strategies of multinational enterprises. He regularly presents his studies in leading international conferences and his research has appeared in peer-reviewed journals as Journal of Management and practitioner-oriented outlets as Harvard Deusto Business Review and the digital edition of Harvard Business Review.

References

1. In China value sales in the online apparel and footwear retailing market reached $32.5 billion in 2013 while they were only $0.2 billion in 2008. Source: Euromonitor International, 2014.

2. S. Mulpuru and M. Gill, “US Online Retail Sales To Reach $370B By 2017; €191B in Europe,” April 14, 2013, available at <www.forbes.com>.

3. Euromonitor International, “Apparel and Footwear Retailing in the Digital Era (Part 2): Regional Trends,” 2014.

4. S. Mulpuru and M. Gill, “US Online Retail Sales To Reach $370B By 2017; €191B in Europe,” April 14, 2013, available at <www.forbes.com>.

5. Fashion market includes apparel, footwear, and accessories (i.e., bags, luggage, watches, and jewelry). Source: Euromonitor International, 2014.

6. P.-E. Gobry, “Amazon’s Endlessly Fascinating Push Into High-End Fashion,” February 19, 2015, available at <www.forbes.com>; W. Loeb, “Amazon.com New High Fashion Push Is Aggressive and Will Encroach on Department Stores’ Turf,” May 9, 2012, available at <www.forbes.com>.

7. The largest player (Otto Group), although primarily focused on e-commerce, is technically a multichannel retailer. The other 3 companies are pure-play online retailers (Amazon, Zalando, and eBay). In 2013, these 4 players accounted together for approximately 25% of the €29 billion fashion retailing market in Europe. Source: Euromonitor International, 2014.

8. P. Ghemawat and N. Pisani, “The Fortune Global 500 Isn’t All That Global,” November 4, 2014, available at <www.hbr.org>.

9. Data for the 12 months ended in June 2014 and refer to average monthly unique visitors. Nike had 15 million and H&M 14 million when considering the same time period. Source: comScore.

10. P. Ghemawat, “Distance Still Matters: The Hard Reality of Global Expansion,” Harvard Business Review, 79/8 (2001): 137-147.

11. D. Bell, Location Is (Still) Everything, (New Harvest, 2014); D. Bell, J. Choi, and L. Lodish, “What Matters Most in Internet Retailing,” MIT Sloan Management Review, 54 (2012): 27-33.

[/ms-protect-content]