By Guido Stein, Ángel Cervantes and Marta Cuadrado

This article, which is in two parts, aims to acquaint readers with the main personnel management policies found in enterprises. It is intended not to be exhaustive but to serve as a reference for managers in charge of their own teams, regardless of their position or department. It was not written specifically for human resources experts, although they too may find this direct academic approach – reinforced by daily practice – rather useful. Part I of this article looked at Performance Management, Recruitment, Integration Processes and started the discussion on Development and Training which continues below.

4.3 Training Medium: Short and Intense Impact

The medium used is one of the most important aspects of career development training. Notably, change in the area of training is always the by-product of a process rather than of an isolated measure. Often times, and especially at the senior management level, there are high expectations on the ability of training activities to produce an immediate change in the way people work. While an isolated training program has a high motivational impact in the short term, it is difficult to achieve sustained improvement in managerial effectiveness without proper follow-up. If this is true for classroom training, where the methodology can have greater motivational impact, then it is even more so the case for Web-based courses.

It is useful to somehow measure the returns on training, despite the limitations involved. An alternative is to conduct follow-ups focused on applicability and transfer to the workplace. Experience tells us that we can only measure training processes in the medium term. An exception to this rule is for those training activities measurable with a high degree of objectivity, such as languages or computer skills, where the acquired level of competence can be compared with generally accepted standards. It is true that an isolated training measure may be very useful in assessing the content and training provider. On the other hand, training programs will have a greater impact where there is a system to measure team leaders’ overall performance and managerial competence levels.

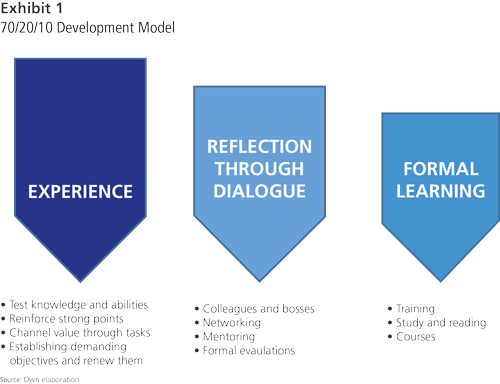

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]The most impactful training processes are those combining various mediums (blended learning). Classroom training is usually associated with high costs and online training with lower costs. This dichotomy is accentuated in periods of crisis, when classroom training tends to be seen as a last resort, given also the added costs (travel, accommodation, meals, etc.) it often involves. Furthermore, new technologies have enabled training solutions impactful in the short term. However, it is necessary to return to the basics: the company’s needs and the objectives of training, which should determine the medium used. We must forget about using online learning as a substitute for classroom training. Both are perfectly compatible if based on clear objectives and personnel needs, and further if training is viewed as an internal communication tool that generates commitment and on certain occasions even pay. Classroom training does not have any meaningful substitute. Exhibit 1 presents the 70/20/10 model, which is based on direct experience, peer review, and classroom training, whether in-person or Web-based. (See Exhibit 1)

The creation of online learning communities where knowledge and experiences can be shared is the beginning of the possibilities that new technologies can bring to training. Today, people are constantly interconnected to the point of creating a phenomenon of social necessity. As well, training program participants create their own groups to stay connected even after the program’s conclusion. These “informal” mediums have great potential for companies. While the creation of corporate social networks is not surprising, it is notable that the company itself can create a medium after a training program through which it can upload information of interest or enable people to stay connected. The creation of theoretically informal mediums should become a clear objective in the areas of HR development, since the impact is entirely different if done at the company’s initiative.

One final aspect to consider is the dependence of training and development on external providers. In this sense and given their importance (they are in direct contact with personnel), the management thereof must be a priority. Given the budgetary pressures of recent years, the buying departments have been having the final say on the choice of provider. This procedure has had several consequences: less weight is given to the final recommendations of training departments (which are those that know company needs in this respect) in regards to the market for consulting services; delays in decision making and program implementation; focus on cost when selecting a provider; often improper decisions, i.e., by viewing providers on equal footing and placing full responsibility over personnel development and training in one company, etc.

The company may get rather comfortable when managing the provider. There is value in frequently tracking progress by distributing quality questionnaires about online content or the training platform management.

The training department must give the provider all necessary information through regular meetings (even when there are no ongoing programs) about training policies and models, company culture, the desired objectives, etc., with various parties on different levels. In short, the training provider must truly know its customer. A foreign bank’s training department head notes:

“Our first contact with a provider would frequently involve a corporate presentation and then a list of the training measures in which they specialised… Our question was always the same: ‘Why are you telling us about solutions before we have told you our problems?’”

5. Evaluation and Promotion

The evaluation and promotion systems have been considered as some of the most sensitive areas of total HR management, given their consequences on the promotion, compensation, and development of personnel within the organisation. The absence of a tested or consistent system can plague human resources departments. The implementation of an evaluation system is usually understood as a sequential process: it begins with a top-bottom evaluation (the boss evaluates the subordinate); then there may be a bottom-top evaluation (the subordinate evaluates the boss), before ending with a 360° evaluation (which may even include assessments of external customers).

The evaluation must clearly account for and engage with the organisation’s culture and values. In this sense, there are companies whose cultures are well suited for top-bottom evaluations. For example, the introduction of bottom-top evaluations in highly paternalistic cultures would produce a rift between the company’s unwritten rules and HR systems, converting the evaluation into a purely formal process without the necessary background. It is essential to have contextualized evaluations within a broader HR development system.

5.1 Skills-Based Management Model

The skills-based management system is one of the most popular models among organisations. This model identifies previously set behaviors (what a person does while carrying out tasks) within each area of responsibility (customer service, focus on results, communication, etc.) for each job. It is based on direct observation and provides managers with information about each of their team members. The results are reflected in the performance evaluation that is shared with the evaluated person and lead to measures such as training courses, participation in multidisciplinary projects or work teams, or the establishment of monitoring processes between the evaluator and the evaluated, or by a third party. This model seeks to develop people. However, one of its priorities is to obtain solid arguments to propose or oppose a promotion.

Evaluation processes, especially skills-based, are highly dependent on the quality of management and the management of evaluators. An evaluation with poor communication can cause serious conflicts. If the system is used to justify previously made decisions, problems are usually greater. The implementation of evaluation systems should therefore be especially linked to human resources development. Transition periods are also required for the evaluated person to have time to make the necessary changes in accordance with the information gathered. In fact, unforeseen consequences such as increased compensation introduce distortions. If an organisation forgets to manage the implementation process and wants to link compensation to its evaluation system prior to its being tested and accepted by the organisation, all it will do is generate conflicts and permanently erase the evaluation system’s benefits.

This is why most evaluation and promotion processes established in organisations fail. Evaluation, promotion, and compensation systems have a very high degree of interdependence: an effective compensation system requires a tested evaluation system, which extends to promotion processes; the greater the consistency and coherence among them, the greater the acceptance by the parties affected.

The evaluation otherwise becomes a formal requirement but loses importance with regards to decision making in relation to personnel and its development.

5.2 Career Paths

This is a document where organisations bring together senior management’s future medium and long-term needs with those of high-potential employees. The following are indispensable conditions for this convergence to occur:

• Previously define the key positions, starting with level 1 (highest priority) and with time, expand to level 2 and, in rare occasions, level 3.

• Identify high-potential employees: internally, through the evaluation procedures described above; external assessment: given the importance of the process, it is common to retain a company specialised in the use of different tools such as simulation tests, interviews, etc.

• Communicate to the candidate his or her inclusion in the plan and obtain his or her acceptance, commitment and discretion, thereby allowing the organisation to choose the development actions suited to the desired direction. By contrast, not communicating this runs the risk of prompting candidates to determine their own development actions, which may not be aligned with the needs of the organisation, or even worse, to pursue professional development outside the organisation.

The first career plan tends to be in combination with a succession plan. Both are perfectly necessary, compatible, and sometimes even integratable. However, it should be noted that succession plans address:

• Contingencies or unforeseen events that may occur in the short term.

• The anticipation of replacement or substitution measures, which are usually temporary.

They are not usually linked to specific development actions for the potential successor, who may also ignore his or her status as such.

6. Compensation

Compensation schemes are among the most complex aspects of human resource management: the need for a coherent compensation scheme aligned with strategy has grown in importance. Technically, pay is a cornerstone on which the other HR systems must be based. As noted, compensation schemes are usually based on valuations of positions, which thus require solid and effective job descriptions.

6.1 Pay Bands

The valuation of positions allows for an objective comparison between them and the establishment of career levels. In large organisations, positions are usually grouped by family (e.g., marketing/communication), professional group, or category to manage the system with greater functionality. A salary band with a minimum and maximum salary is assigned. Importantly, it is better to refer to positions than to who occupies them at any given moment. When someone would like a salary raise that exceeds the given band, the scheme would aid in deciding whether to grant the request or make an exception, which would involve a decision by senior management.

Once the band and career level system with the corresponding positions are in place, the personnel are “incorporated” and mismatches are analyzed (there always are): professionals below or above their pay bands. These mismatches do not usually have a short-term solution but are processes that must be carefully followed to maturity.

The structure described above helps give consistency to fixed compensation and other complementary schemes. One example is geographical mobility, which is taken into account under certain circumstances, such as career level, the city or the country of destination, family status, etc. It must allow room for negotiation, but the less it is amended, the fewer and less adverse the effects will be to manage and resolve, as may be appropriate.

Career levels and pay bands also serve as a reference for establishing maximum and minimum figures for annual or multi-annual variable compensation. However, most important to variable remuneration are the objectives and criteria on which it is based.

Everything described above especially applies in organisations committed to internal promotion. A compensation scheme helps maintain internal consistency and becomes a management facilitator (along with evaluation and training systems) when structuring professional careers. Problems often arise when organisations bring in people with experience in other companies and sectors en masse, as did many Spanish banks prior to the crisis, amidst the expansion and mass branch openings. Some firms had to completely redesign their compensation schemes, and others were left to languish. Organisations should therefore define a career development model when implementing a compensation scheme.

Another aspect to consider is the organisation’s pay relative to the market. A pay scheme may be compared with sector-wide averages by participating in objective wage surveys. If an organisation decides to pay less than what is offered in the marketplace, it will be more vulnerable to losing talent, despite an internally consistent pay scheme. In short, internal equity is based on the maxim “similar positions, similar pay,” and external, on comparisons with bands offered outside of the organisation, which indicate a competitive system.

6.2 Variable Compensation

Compensation systems are dynamic, require constant updating, and involve a core strategic component, which acquires special relevance in the management of variable compensation. Performance-based variable annual compensation is the most common. In business development positions, achieving certain sales figures implies a full or partial bonus; in the case of senior management, pay is sometimes linked to share price, local or overall company performance, business growth, etc.; in other positions in which firms want to measure service quality, customer reviews or employee response times may be taken into account. In any case, it is vital to find objective and quantifiable points of reference, though not necessarily closed to interpretation.

However, major problems arise when individual targets are based on the exercise of position-specific functions. This increasingly widespread practice necessarily requires a proven, clear, and objective performance evaluation system. If evaluation systems were not consistent with pay schemes, incorporating an individual performance component in variable compensation schemes would clearly cause conflict.

Variable compensation merits the following additional considerations:

• There must be a sense of solidarity; that is, everyone involved must share in the company’s successes or failures to some extent. It must be standard practice that some of the objectives are beyond the scope of the position (N + A) level; others, on the employee’s own or collaborative level (N); and others, personal (P). Objectives are usually a weighted combination of the individual and team.

• The incorporation of corporate short and medium-term objectives. There is a prerequisite that gives effect to such objectives: they are those which have more influence over total variable compensation, determined in proportion to the effort needed to achieve the objectives.

• Removal and recovery. If performance is not solid, it will be difficult to maintain incentives. But they will need to be recovered as soon as possible given the difficulty in certain sectors to attract and retain talent.

• The crisis has favored the so-called “flexible compensation” model. Increased tax burdens together with wage freezes (or even reductions) have reduced disposable incomes. Flexible compensation allows employees to purchase products or services with their gross salary, thereby being subject to lower tax withholdings and increasing their disposable income. It is an increasingly popular trend, but with certain limitations: the list of products/services is fixed and the system is vulnerable to tax changes.

Regardless of whether the objectives and rules of variable compensation are promptly communicated, we should stop and reflect on whether a compensation system is transparent. This is a decision that goes beyond strategy and involves the organisation’s culture and values. Informal transparency (especially among people belonging to the same or similar level) is, has been, and always will be present; it is inevitable, even with institutional communication based on transparency. Rumors, conflicts, and jealousy are inherent to compensation systems in particular, and to other HR policies in general.

In summary, compensation schemes fail due to the following reasons, among others:

• Not being clear about the benefits of their implementation when deciding to implement.

• Failure to properly manage implementation expectations.

• Impatience in implementation.

• No proper updating (new positions, corporate mergers, etc.).

• Not having a compensation scheme consistent with other HR systems and the organisation’s culture.1

The key question is what to measure. We must keep in mind that individual goals flow from a stream deriving from the company’s strategy and overall objectives.2 There are systems that do not measure what is important for the company at a given time; these are indicators established in the past that do not measure the degree to which current objectives are being achieved. For example, some companies backed by a veteran sales force with a portfolio of large customers strive to measure the number of new customers, whereas what matters is retention. Another example is tracking sales when the real goal of the company is profitability.

The main difference between the various compensation systems implemented by prestigious consulting firms is based on position valuation methods and the scope of application. Thus, Hay Group’s skills-based model allows for a more natural fusion of performance evaluation and compensation; Mercer’s solutions have a more strategic component for its heightened focus on long-term compensation; Towers Watson’s system provides a comprehensive vision of compensation, both in terms of the term as well as the different organisational levels; and so on.

A solid compensation model should be able to distinguish a “good professional” with adequate performance from one who is not and whose performance is short of adequate; but above all, it should clearly differentiate between “very good” and “good.”3 Any classification is difficult to manage. Only objective criteria, such as salary bands and performance evaluations, help lead to more effective management.

7. Internal Communication

It should be stressed that communication is an ongoing process in which people participate whether knowingly or not. Mere physical presence suffices.

It is common for internal communication to be integrated into the human resources departments. This trend was accentuated with the popularity of employee portals. However, it is also increasingly common for internal communication to be integrated into dedicated communications departments (mediums of communication, institutional relations, corporate social responsibility, etc.) to bring greater consistency to messages.

The decision to integrate internal communication into one area or another must be based on several factors. Experience has generally told us that the communications department is closer to senior management than to HR, which grants it more information and converts it into a major player in managing the corporate intranet, a crucial medium. On the other hand, HR usually has a more comprehensive vision of and greater sensitivity to personnel. It further takes charge of another relevant digital medium: the employee portal. In any case, the least desirable outcome is an intermediate situation in which two departments force internal communication; because it is very difficult to act in sync (e.g., in developing overall company communication plans), such efforts can distort messages and trigger conflict and negativity.

The company’s personnel comprise the main players of internal communication; therefore, the more communication engages the personnel, the more effective it will be. Again, an effective internal communication policy is based on its consistency with the culture (common language based on a common culture), the organisation’s values, its integration into the HR strategy and, therefore, into the company’s business vision.

Naturally, communication is a process that requires planning and concrete objectives. This is what determines the message (the what) and the medium (the how). Just as effective external communication requires having a clear action plan for the company’s message to reach the various segments of the public with the degree of impact and penetration desired, smooth internal communication must find a way to reach the “internal customers” without having its message distorted along the way. Transparency has become a magic word, and though few companies can afford to be really transparent about decisions that affect their personnel, all boast about having this feature of candid communication.

Communication is not only meant to inform; it is bidirectional and helps prevent conflicts and problems at their source. Therefore, traditional communication channels are changing. The intranet and corporate newsletters help keep the staff informed, but if the objectives of internal communication go beyond pure information, companies may have to consider additional channels. For example, an increasingly popular trend is to use communication as a means of enhancing commitment to the organisation; to this end, companies undertake a variety of corporate social responsibility activities on behalf of employees, also open to family members and financed by the company itself. One example: the CEO of an international advertising company created an internal social network as a single channel of communication within the company. Over the months, the communication channel became a collaborative tool for certain projects with consequent cost savings. In addition, the emotional commitment (key to an advertising agency) was enhanced when, for example, staff would visit other countries and request contact information of locally based company peers. Of course, they ended up meeting.

There are also informal channels, which operate outside of and parallel to those established by the company, and which constitute the domain of the rumor mill. Two prime examples are the coffee machine and smoking areas at the entrance of the building: employees at various levels and departments gather spontaneously in these environments without any prior agenda; moreover, there are customers, shareholders, and providers: What better place is there to gather and compare information, expectations, wishes, or complaints? We should also add physical and virtual corridors, such as social networks of any kind.

Effective internal communication manages the rumor mill and does so notably by asking rather than telling, because the most important part of communication is listening to what would otherwise remain unheard. Communication is behavior; hence the quintessential corporate internal communication channel is the relationship between the manager and team members, top to bottom, out of a sense of responsibility, and bottom to top, out of loyalty; the rest are tools that must be managed.

8. Final Thoughts

Personnel management policies are more effective when they combine strategic with tactical visions; in other words, when they account for the short term without jeopardizing the medium and long terms.

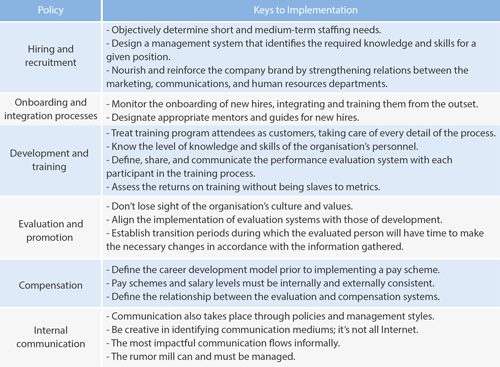

Some practical comments are attached in Exhibit 2.

About the Authors

Guido Stein is a Professor at IESE Business School.

Ángel Cervantes is an HR Consultant.

Marta Cuadrado is a Research Assitant at IESE Business School.

References

1. The CEO of a small financial institution (less than €20 billion in assets) recently proposed the implementation of a compensation model at the management committee. Until that point, they had been working with external hires; they did not have a performance evaluation system; they had a highly variable model based on business objectives for the short and medium term; they were clearly paying above the market average; they were not subject to much union pressure; there was little unwanted rotation; and the company was performing well. Do you think that the bank needs a new compensation system? What problems would it solve? What new problems could its implementation create?

2. The principle that the objectives that determine pay must be aligned with overall company objectives is not always complied with.

3. Which must be compatible with the untying of evaluations of potential from compensation.

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-100x70.jpg)