Business executives do not seem to heed the lessons of decision research, and continue to make strategic decisions without considering common errors. Below, Phil Rosenzweig argues that the problem is not that executives do not wish to make better decisions, but rather that decision research has done an inadequate job of describing the realities of the decisions they face.

From the days of Adam Smith, economic theory has rested on the shoulders of homo economicus – the rational actor who makes choices consistent with utility maximisation. Whether these decisions involve what we buy, how we strike a balance between labor and leisure, or determine how much to spend and save, they were assumed to reflect clear-minded judgments based on enlightened self-interest. The free market economy, as the aggregation of many such rational choices, should be left to operate with minimal interference according to principles of laissez faire. Why, after all, should the government intervene when the invisible hand worked so well efficiently for the benefit of all?

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]Over the last decades, a mountain of evidence has shown that people do not always make judgments and choices as predicted by economic theory. Research in behavioral decision theory, much of it conducted by cognitive psychologists, revealed that people employ rules of thumb, called heuristics, which are often useful but also lead to systematic errors, or biases. By now the list of biases is very long. We know that consumer choice can be influenced by the way options are framed. Investors misunderstand the nature of random events, imagining that several gains in a row means a correction must be due, or that a string of losses means that gains will follow, an error known as the gambler’s fallacy. People fall victim to the sunk cost error, throwing good money after bad in an effort to recoup what they have lost. They are prone to overconfidence and believe they can do more than they really can. They search for evidence that will confirm their wishes, rather than ask questions that may reject a desired outcome. Add these together and a new picture emerges. Rather than thinking of people as rational actors, they may be better described as prone to irrationality.

The findings of behavioral decision theory have made important contributions to fields ranging from consumer behavior, financial investments and public policy. At the same time, however, it has been noted that many business executives do not seem to heed the lessons of decision research. They continue to make strategic decisions without considering common errors. They continue to demonstrate overconfidence and make what seem to be ill-advised decisions. By way of explanation, some researchers have alleged that executives might imagine themselves to be immune from decision biases, perhaps due to hubris. Why else would they disregard lessons that have been so powerful in other domains?

My view is different. If executives have not always acted on the lessons of decision research, it is not because they are unaware of common biases, or even in denial about the perils of decision errors. Rather, it is because strategic decisions are different from routine decisions in many important ways. The problem is not that executives do not wish to make better decisions, but rather that decision research has done an inadequate job of describing the realities of the decisions they face.

Lessons from the Lab

To understand why behavioral decision theory doesn’t always capture the essence of management, let’s recall that research in cognitive psychology has commonly taken place in laboratory settings. The lab allows us to isolate the mechanics of cognition with precision, by showing how specific cues lead to given actions. The results are valid, reliable, and replicable. Decision research has made such profound contributions because of the precision of its use of rigorous experimental methods.

In order to neatly capture human cognition, the sorts of judgments and choices captured in laboratory settings tend to have a few features in common. First, they involve choices among options that we cannot change, or judgments about things we cannot influence. Second, they ask the respondent to make the decision that suits them best, without regard to anyone else.

These laboratory experiments are a reasonable approximation of many kinds of routine decisions. Think of a shopper in a supermarket. You can pick from among the products on the shelf, but you have no ability to change the selection, or improve the quality of the products, or even alter the price. Moreover, you make the choice that suits you best. You’re really not concerned with what anyone else is buying. Performance is absolute. The same goes for most personal investment decisions. You may buy a share of Google or a share of Vodafone, but you can’t influence the share after you buy it. Again, you want high returns but aren’t trying to do better than others. The goal is to do well, not to finish first in a competition.

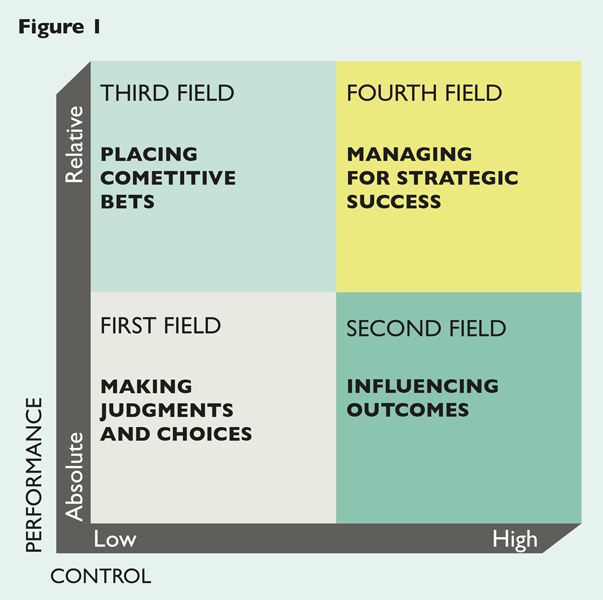

These decisions can be described by the quadrant in the lower left of Figure 1, called the first field, where control is low and performance is absolute. For these sorts of judgment and choices, it is good advice to be aware of our propensity for errors, and take steps to guard against them. As Daniel Kahneman writes in Thinking, Fast and Slow, we should learn to recognise when we’re prone to errors, and take steps to ward off such mistakes.

How Decisions Differ

Yet the reliance on experiments has come at a cost because not all decisions belong in the first field.

Many of the most important and consequential business decisions are not in the lower left quadrant at all. When we can influence outcomes, we’re in the second field. Here, executives don’t just make choices from options presented to them, but have to mobilise resources to bring about a desired result. They can exercise influence or control over outcomes. The mark of a successful manager is precisely his or her ability to shape outcomes, bringing about results that would otherwise not happen.

When we need to outperform rivals, we move up to the third field, where we place competitive bets.It’s in the fourth field, however, that both two dimensions come together. Here, business executives do not simply make decisions that suit them in absolute terms, but do so with an eye to competition. They are often engaged in tough competitive battles, such that the decisions they make are aimed to outperform rivals, who in turn are trying to outperform them.

These decisions, which involve not only strategic analysis but also the need to mobilise people to achieve a desired end, include the most complex and consequential of all. Yet for all their importance, fourth field decisions have not been the subject of systematic research; attention in decision theory, on the other hand, has tended to focus on the first field. Thus the paradox: the simplest decisions have received the most study, while the most important have received the least investigation. Small wonder, then, that executives may not seem to heed the lessons of behavioral decision theory. The realities of the decisions they face are not adequately captured by carefully controlled laboratory studies.

A Blend of Skills: Left Brain, Right Stuff

What is needed for effective business decisions? As Figure 1 suggests, a single approach cannot be followed everywhere. Rather, a different mindset is called for depending on the decision at hand. We need a blend of seemingly contradictory skills, which I call Left Brain, Right Stuff.

When it comes to judgments about things we cannot influence where performance is absolute, in the first field, it is sufficient to recognise the danger of common errors and to try to guard against them. There is no point in being optimistic or showing any wishful thinking when we cannot influence the outcomes. We need to train our reflective mind to alert to bias. That’s what is meant by Left Brain – a misnomer in the sense that not just the left hemisphere is used, but a well-accepted term for our rational and reflective mind.

However, when we can influence outcomes – when we have to perform a task, whether in sports or music or performing in a play – positive thinking matter. To achieve our best, a high degree of self-belief is useful. Furthermore, when we overlay the need to outperform rivals, a high degree of self-belief is not just useful but indeed essential. In a competitive setting, where many rivals vie for a very limited prize – in the extreme, winner-take-all and only those who hold a level of self-belief that is by some definition excessiveness will be in a position to win.

For these sorts of decisions, firmly in the fourth field, we need to do more than watch out for biases. We also need to inspire, to reach for stretch goals, and to extend ourselves to surpass what we have done before. That calls for the Right Stuff, a term popularised by Tom Wolfe in his 1979 book about the US manned space program in the 1960s and 1970s. The Right Stuff isn’t a matter of bravado, or recklessness, or courting danger. It’s often careful and disciplined. Yet it means pushing the envelope and seeking to do more than what we’ve done in the past. The key to successful strategic decisions? Not merely warding off the semblance of bias, but the ability to channel positive thinking to achieve higher performance.

Rethinking Confidence and Overconfidence

Once we move from routine judgments and choices, found in the first field, to the complex strategic decisions of the fourth field, we’re forced to take a fresh look at a number of commonly held views. Most prominent among them is the notion of overconfidence. Of all the biases that are said to afflict us, perhaps the most widely mentioned is overconfidence. Research has found that people are often too sure of themselves, often likely to overestimate their abilities, and frequently willing to think they are better than others. That is why we are routinely admonished to beware of the dangers of overconfidence, and to take pains to avoid it.

At first glance this seems reasonable. After all, overconfidence means excessive confidence, and is often attributed after the fact when something has gone wrong. Surely it makes good sense to guard against excessive confidence. Who wouldn’t agree?

But when we look closer, the story becomes more complex. Of course there’s no value in optimism when it comes to a decision we cannot influence. There is nothing to be gained from wishful thinking or an elevated level of confidence when it comes to things that are out of our control, like the roll of dice, or the movement of the stock market, or tomorrow’s weather.

But for things we can influence, a level of self-belief that goes beyond what we may have done before can help us achieve new heights. Here, positive thinking and the deliberate application of self-efficacy can improve performance. In that case, we should ask whether an elevated level of confidence is excessive or not? By one definition it is, but by another such a level of confidence is really not excessive at all, but actually useful. Furthermore, in a competitive setting where we must outperform rivals, an elevated level of confidence is not just useful but even necessary. In which case, the very meaning of “overconfidence” demands a fresh examination, as what seems excessive by one definition is essential by another. Rather than simplistic assertions to avoid overconfidence, we are forced to think more deeply about the relationship between confidence and performance, and to confront the realities that face manager who need to inspire others to achieve demanding goals.

A New Frontier in Decision Making

In recent years, it has been alleged that strategists should do a better job of heeding the lessons of decision research. I’ve made a very different argument. Rather than implore executives, once again, it’s up to us, those of us who research and write about business need to change how we think about decision-making. Unlike many routine decisions, where control is low and performance is absolute, leadership decisions are distinctive in a few ways. The aim is to shape outcomes, not merely choose from among options set before us. They are, in addition, often related to competition and therefore add a relative dimension. A winning decision is one that lets us do better than a rival, which necessarily means taking risks.

Think of the core idea in terms of dialectics. For years, the dominant view about decision making – that people are rational decision makers was a thesis. More recently, the contrary view , that people suffer from common biases and errors , was an antithesis. What is needed today is a new synthesis that takes us the next step, and that does a better job of illuminating the nature of decisions faced by business leaders. The most complex and consequential decisions they encounter are fundamentally different from the routine choices and judgments that have been so elegantly captured in laboratory research. To make winning decisions, leaders need to draw on their dispassionate and reflective minds, and also to summon optimism and inspire others. They need, in a word, the virtues of the left brain as well as the audacity of the right stuff.

About the Author

Phil Rosenzweig is professor at IMD in Lausanne, Switzerland, where he works with leading companies on questions of strategy and organization. He is author of The Halo Effect (Free Press, 2007), and Left Brain, Right Stuff (Profile, 2014).

[/ms-protect-content]

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-100x70.jpg)