By Sime Curkovic & Thomas Scannell

The decision to manage supply chain risks constitutes a major undertaking for most firms. In this study, Sime Curkovic and Thomas Scannell use data from 46 firms and SCM managers to identify which factors affect the decision to develop a system for managing supply chain risks, and explain how these factors can influence the level of success.

Factor 1. Corporate Strategy

Firms overwhelmingly agreed there is no obvious single application for managing supply chain risks on the market. Most firms (61%) are only using existing SCM applications for managing risk. In the absence of risk management applications, these firms are building risk considerations into traditional SCM applications (e.g., spend, contract, & inventory management, demand planning, benchmarking, building long-term partnerships, etc). An additional 6% said they would like to implement a SCM risk application in 1-2 years, and another 13% said they are considering it. This indicates that while specific supply chain risk applications do not exist, interest levels are very high (80%). The following questions were also asked on 1 to 7 scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree): 1) Managing supply chain risk is an increasingly important initiative for our operations; and 2) Without a systematic analysis technique to assess risk, much can go wrong in a supply chain. The means for both questions were well above 5.00 and had very small amounts of variance. Again, interest and need levels for supply chain risk applications remains high.

18% of the firms said they will spend over $1M in services, technology, and personnel to support managing supply chain risks, while 7% actually plan on spending over $5M. Another 52% said they plan on spending more modest amounts of less than $500,000. 30% would not answer the question because of its proprietary nature, but indicated a moderately large amount of spend was planned. The manufacturing firms look very similar in their higher spending efforts with a focus on supplier failure, whereas the non-manufacturing firms indicate lower spending levels with a focus on logistics failures.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]These questions were also asked on 1 to 7 scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree): 1) Our spending intentions for managing supply chain risks are very high (mean=3.37, var.=2.47); and 2) We do plan on investing nontrivial amounts in managing supply chain risks (mean=4.30, var.=3.77). In this study, there was dedicated funding for managing supply chain risks and 86% indicated that such budgets will increase or stay the same. However, only 42% will come from specific SCM departmental budgets and 60% indicated that SCM takes ownership of such investments. Managing risks is just now reaching the core of traditional and mature SCM applications.

Factor 2. Supply Chain Organisation

Risk management in this study was mostly handled by a corporate function, usually dealing with insurance companies and some security issues. However, risk management in the supply chain has emerged rather recently and it appears many managers and functional areas are not involved. The following questions were asked on 1 to 7 scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree): 1) My workplace uses supply chain risk managers who work closely with corporate risk mgmt (mean=2.53, var.=3.03); and 2) I fully understand the activities being performed by our risk management group (mean=4.00, var.=2.66). On a higher level, the corporate function is involved with risk management and has contact with insurance companies, but does not necessarily coordinate risk management activities in the whole group, not does it appear to develop directives.

Most of the firms in this study have outsourced one or more of its non-core business functions. For financial reasons, resource constraints, and/or the need to tap into expertise they do not have, outsourcing has become a key aspect of many strategic initiatives. The following question was asked on 1 to 7 scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree): 1) We are planning to outsource all or some of our risk management functions. The mean was only 2.25 with little variance. The organisations in this study have no intentions to outsource risk management and are strongly inclined to develop these skills internally by purchasing a risk management application for internal use, and specifically in the SCM area. However, the following questions were asked on 1 to 7 scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree): 1) There is no single set of tools or technologies on the market for managing supply chain risks; and 2) Managing supply chain risk is an increasingly important initiative for our operations. The means were well above 5.00 and had small amounts of variance. Again, interest and need levels for supply chain risk applications remains high.

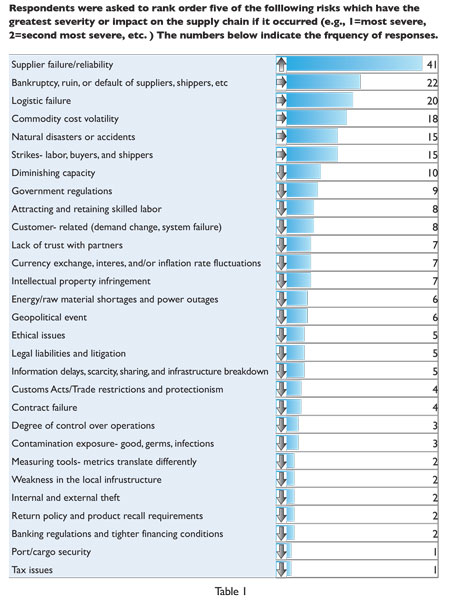

Respondents in our study see a broad set of risk factors that pose a disruption to their supply chains. These risks did not vary much by industry, and most were shared (see Table 1). Supplier failure/reliability was the top risk factor and common across all respondents. Bankruptcies of suppliers, logistics failure, commodity cost volatility, natural disasters, and strikes/labor disputes were distant seconds. The non-manufacturing respondents were more inclined to place a higher priority on logistics failure, which is not surprising since they were mostly made up of distributors and a retailer.

While the majority of the manufacturing respondents identified supplier failure as their top risk factor, they also attributed the majority of their downtime in operations to supplier failure. Commodity cost volatility was also a growing concern, but with limited amounts of systems to manage its risk. For example, the majority of the firms strongly disagreed that they were using hedging strategies and speculation for managing supply chain risks (and yet it was identified as one the top risk factors).

The firms in this study are recognised as leaders in SCM and several have received formal recognition by industry associations for their ability to use SCM applications in a customer-driven manner. For example, these firms were very satisfied with their supply chain group’s performance on the following issues: after sales service performance, supplier reliability, inventory management, delivery reliability, order completeness, damage free delivery, and meeting customer service levels. However, they did not show a proactive commitment to risk management. These questions were asked on 1 to 7 scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree): 1) We are prepared to minimise the effects of disruptions (terrorism, weather, theft, etc.); 2) Proactive risk mitigation efforts applied to the supply chain is common practice for us; and 3) We can actually exploit risk to an advantage by taking calculated risks in the supply chain. The means were very low and had small amounts of variance.

Factor 3. Process Management

This study showed that documenting the likelihood & impact of risks was not a key part of SCM and that supply chain risk information was not readily available to key-decision makers. Furthermore, very few of the firms are actually able to exploit risk to an advantage by taking calculated risks in the supply chain and even fewer were prepared to minimise the effects of disruptions. These questions were asked on 1 to 7 scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree): 1) A key part of our supply chain management is documenting the likelihood & impact of risks (mean=4.20, var.=2.86); and 2) Supply chain risk information is accurate and readily available to key-decision makers (mean=3.87, var.=2.78). There was some debate as to the validity and usefulness of tools to operationalise the process. The managers did tend to prefer approaches that combine subjective and objective measures because this allows them some freedom rather than being pushed into taking decisions solely on complicated numerical analysis. Failure Mode Effects and Analysis (FMEA) is a mainstream tool used to collect information related to risk management decisions for most companies in an engineering capacity, but not in a supply chain capacity. There were several documented procedures to complete an FMEA across industries in this study, especially in automotive. Most managers supported a modified version of the tool that could be used to help evaluate the risk of SCM decisions.

Factor 4. Performance Metrics

This study demonstrates that the measurement of risk factors does not necessarily require a new or unique set of performance measures. For example, one firm used average on-time delivery as a measure of supplier performance and chose to look more closely at the peaks and valleys of this indicator to determine the supplier’s risk impact on its own delivery performance. In another example, key metrics were established to measure the risk associated with key suppliers and their performance against service level agreements. Supplier agreements were then aligned with the established levels negotiated with the company’s key customer agreements. Supplier risk rankings, similar to credit scores used in the financial industry, were often established to measure suppliers on stability, contingency planning, and on-target delivery performance. In general, the development of specific risk management performance metrics in the supply chain was lacking in this study.

Factor 5. Information & Technology

In this study, firms had information of what goes on in other parts of the supply chain. An issue on information was not suggested as it was asked on a 1 to 7 scale (not satisfied to very satisfied); How satisfied are you with your supply chain group’s performance on ‘Visibility’ (detailed knowledge of what goes on in other parts of the supply chain – e.g., finished goods inventory, material inventory, WIP, pipeline inventory, actual demands and forecasts, production plans, capacity, yields, and order status). The mean was modestly high (4.26) with a very small amount of variance, as was their agreement that their company uses real-time inventory information and analytics in managing the supply chain. Furthermore, the questions were also asked on 1 to 7 scale (not used to extensively used): To what extent are the following used in managing your supply chain and risks within it: 1) Information gathering; and 2) Establishing good communications with suppliers. The means for both questions were very high (well above 5.00) and had small amounts of variance. In this study also, information delays, scarcity, sharing, & infrastructure breakdown was seen overwhelmingly as one of the lowest rated risk factors both currently and for the future.

These findings are not surprising given that firms in this study showed that a wide variety of information-based technology and applications are being spent for their SCM efforts (e.g., ERP configuration systems, electronics reverse auctioning, radio frequency identification, Collaborative Planning Forecasting and Replenishment – CPFR, etc.), but very few firms showed that their technologies are being used to support risk considerations. Respondents agreed that the key to improved supply chain visibility was sharing information among supply chain members.

Most of the technology supported the following SCM applications for the purposes of managing risk: information gathering, partnership formation and long-term agreements, supplier development initiatives, inventory management, spend management and analysis, credit and financial data analysis, and contingency planning. Overall, the firms in this study did not engage in proactive modeling exercises as part of a concerted sales and operations planning process.

Concluding Comments

Managers agreed that without a systematic analysis technique to assess risk, much can go wrong in a supply chain. Analysing the risk associated with SCM is a relatively new subject, and little has been done to assist managers with this process. But one thing is certain, documenting and analysing risk must be an essential part of continuous improvement. It becomes critical to have an easily understood method to identify and manage risk.

While many factors have been cited as influencing the predisposition towards having a system for managing risks in the supply chain, certain factors were identified as having a critical impact on predisposition and progress towards this. These factors included: Corporate Strategy, Supply Chain Organisation, Process Management, Performance Metrics, and Information & Technology. These factors describe a situation where the respondents saw managing supply chain risks as an extension of SCM. They also describe a situation in which respondents recognised that success with managing risks requires cross-functional teams and cooperation. There seems to be recognition that succeeding requires more than simply introducing a new program or department. Rather, it is an undertaking that requires the participation of multiple parties working together. It is argued that these various factors act to pre-condition the firm and its systems to the introduction, acceptance, and progress on managing risks in the supply chain.

About the Authors

Dr. Sime Curkovic is a Professor and Director of the Integrated Supply Management Center at Western Michigan University. His research interests include environmentally responsible manufacturing, green purchasing, total quality management, supply chain management, and integrated global strategic sourcing. Dr. Curkovic’s publications have appeared in the Journal of Supply Chain Management, the IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, the Decision Sciences Journal, the International Journal of Operations and Production Management, the International Journal of Production Research, Supply Chain Management Review, and the Journal of Quality Management.

Dr. Thomas Scannell is Professor of Management at Western Michigan University. His research interests include innovation management, supply chain integration and process improvement. His articles have appeared in Decision Sciences Journal, Journal of Operations Management, Journal of Business Logistics, Sloan Management Review, and Journal of Product Innovation Management.

[/ms-protect-content]

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-100x70.jpg)