Implementing Enterprise-Wide Transformation has proven to be troubling – well-regarded consultancies’ research can back this up. In this article, Doug Ready discusses the five embedded tensions that cause transformation difficulties and what can great change leaders do to improve these odds.

The Transformation Leader’s Job

Research from well-regarded consultancies such as McKinsey, in addition to my own research and work with companies from around the world indicates that two thirds of large-scale transformation efforts fail to achieve their intended objectives. So, what can we do as change leaders to improve these odds? The challenge can be broken down into what transformation leaders do, but we also need to examine the skills and insights they will need to bring to the table to address the depth of complexity of leading deep change across global companies. One way to look at the challenge is to break it down into two parts: the “doing” and “being” aspects of the transformation leader’s job. But first let’s examine why this is such a persistent challenge for so many leaders who are trying to drive enterprise

transformations successfully.

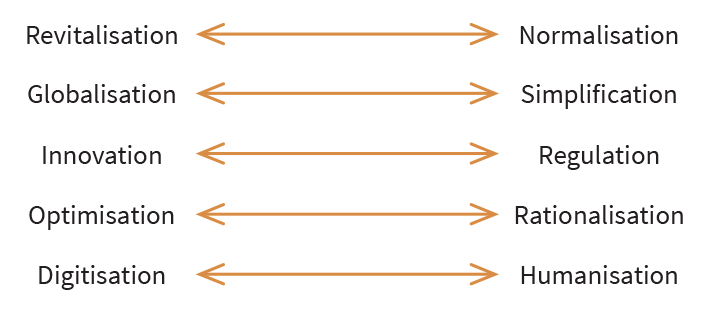

Why has Implementing Enterprise-Wide Transformation proven to be troubling? When challenges persist it is often because there are embedded tensions or paradoxes that surface that seem unresolvable. There are at least five embedded tensions that make the successful implementation of enterprise transformations persistently difficult. They are:

Let’s examine each of these tensions…

1. At the core of many transformation efforts is the desire to breathe new life into the organisation – to revitalise ways of thinking, behaving and working. A leader’s typical and, in fact, reasonable response is to introduce a change initiative into the organisation. One of the problems that employees face is that a change initiative often morphs into multiple change initiatives, and seldom are these initiatives coordinated or provided the context required to make sense out of them. With so many “change programs” coming at people from so many directions, employees can easily become “change weary”, and yearn for some level of normalcy. Thus, we find ourselves in the conflicted situation of needing revitalisation but

desiring normalisation.

2. It is increasingly commonplace that doing business today means doing business globally, but the complexities brought on by globalisation often are in conflict with the need for organisations to make it simple for customers to do business with them. As we search for growth in areas where the contextual distance is widening, and the rules of engagement are less familiar, leaders struggle with creating organisational responses that address the need to master globalisation while offering customers and employees optimal simplification.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

3. Innovation is the heartwood of any organisation’s growth plan. It is what stimulates the creation of new business models, products, services, and ways of working. Yet, so many organisations, particularly in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, are saddled with trying to do business, let along innovate, under increasingly crushing regulatory environments. To be fair, for some organisations this burden has been brought about by their own doing. But for many, it is a stifling tax on a company’s capacity to find creative approaches in solving unmet customers’ needs. As such we struggle with the tension between the desire to boost innovation and the need to operate under

increasing regulation.

4. Customers have not only more power – they have all of the power in today’s business quotient. Organisations are struggling to provide solutions that are better, faster, cheaper and increasingly customised. Optimisation is the name of the game. Yet, in order to remain competitive with players that are more nimble or have dramatically lower overhead burdens, repeated cost rationalisation has become a way of life. Leaders today are in a seemingly endless struggle to reconcile the tension between optimising benefits to customers while rationalising their costs of doing business.

5. Advanced technology is at the core of virtually every company’s business model today, and the strategic use of technology has transformed how value is created in industries ranging from car services, to banking, to hotel bookings, to manufacturing. Entire value chains are being digitised. Yet, the onset of ubiquitous digitisation is occurring at the same time that individuals are yearning for a sense of belonging or meaning in their communities and in their organisations. Leaders of many of today’s largest companies are struggling with how to reconcile the increasing need for the digitisation of their business models with the increasing desire to create organisational climates that have an authentic sense of humanisation – creating companies that are driven by an overarching

sense of purpose.

What Great Transformation Leaders Do

Among many other tasks, great change leaders share five things that they do exceptionally well.

First, they recognise that there exists a series of embedded tensions that make the challenge all the more complex. There are no easy answers; however, the leader’s bedrock commitment to help reconcile these tensions is paramount – and a good start. That means above all committing to an on-going communications and listening campaign so people know what’s going on and know how they might contribute to the transformation effort – and know that they are invited to do so. This process starts by the CEO and top team telling powerful and compelling stories of where the company has been, where it is now and where it needs to go – and why. In a sense, great transformation leaders are storytellers-in-chief. They link their companies’ heritage of the past with its current challenges and indicate that in order to transform successfully, that their organisations should strive to be purpose-driven; performance-oriented; and principles-led. This is easier to say than to do, which is why the next step is critically important.

Next, the leadership of the change effort can’t begin and end with the top team, the top 100, or the top 1,000. It has to be an all-hands-on-deck engagement. The change leader must signal that enterprise-wide transformation will be a collective accountability, with leadership for the effort distributed throughout the organisation. The change leader will need to be skilled at network orchestration in order to have the transformation initiatives integrated so as to minimise change weariness brought on by uncoordinated efforts. This is a critically important step, because without calling for a collective leadership capability it is easy to see how business, regional or functional “silos” will form, which tends to create zero-sum behaviours, making smooth transformations nearly impossible to execute. But this is where the truly hard work begins.

Third, change leaders must go beyond storytelling, motivation and mobilisation efforts – they need to provide the resources to skill-up the company and build next generation mission-critical capabilities to propel them to their desired future state. This includes capital improvements, process improvements and building new talent and cultural capabilities. The challenge here is to avoid “blame-game discussions” that will threaten existing leaders who have spent, in many cases, decades doing exactly what we have asked them to do – they have built successful businesses or highly efficient functions, but are now being asked to change what has led to their success to date. This success has often led to behavioural and cultural patterns, which are very difficult to change, because today’s heroes in many companies are the stewards of yesterday’s business models, which ironically, have led these companies to their current state. This is the point during which the honest conversations that have hopefully taken place during the first two stages will pay off so that next-generation capability building can commence without too much energy wasted on defensiveness and blame-gaming.

Fourth, leaders and employees will need to build a powerful sense of mutual trust. This is where the will to persevere and the courage to address long-accepted doctrine takes centre stage. The messaging provided about the characteristics of the new organisation will need to be backed up with the systems, processes and rewards to make the journey authentic. In other words, if leaders state that their organisations will become the world’s benchmark in customer service then employees will need to see that resources have been committed to build that capability and that rewards are distributed to those who exemplify world class customer service behaviours. In short what great transformations leaders are doing during this stage is aligning “promises made with promises kept”.

Finally, it has become increasingly clear that the transformation journey is a never-ending one. This almost appears to be cliché at this stage, but needs repeating nonetheless, because these leaders are taking their people on a journey of continuous revitalisation and renewal – not a one-time change effort. Change leaders must combine words, motivation, capability-building efforts and trust with a relentless commitment to implementation and discovery. While implementing large-scale change leaders should be asking: what are we learning as we’re progressing? This will help to create a culture of agility and resiliency that will pay dividends out into the future, making large-scale change a collective challenge to be embraced together.

The “Being Aspects” of the Transformation Leader’s Job

In 2015 I conducted a detailed study of approximately 40 senior leaders who were all engaged in bringing about deep change in their companies. The companies I selected were based in Europe, North America, and Asia because I wanted to see if any cultural considerations influenced how transformation leaders went about their work. I asked the chief executives of those companies to let me speak with those in their organisations whom they felt were exemplars of successful enterprise transformation change agents. They all had enterprise-wide accountabilities, even if they were embedded in a business, a function or even a large-scale project. I conducted deep dive interviews with them, seeking to better understand what it was within them that helped them to emerge as successful change leaders. These interviews certainly reinforced the notion of the “doing aspects” of leading transformation, but what was even more telling was that these leaders all spoke to another element – what I refer to as the “being aspects” of leading. This second attribute turned out to be just as much a matter of “mindset” as “skillset”, and I found six elements of the transformation leader’s mindset that all of these leaders seemed to share.

1. Purpose – these leaders placed a strong premium on helping their employees to connect the dots between their companies’ organisational purpose and their quest to extract individual meaning from those statements. This fueled the motivation to dig more deeply to drive change and to feel a powerful connection to their companies, making the change

journey a worthy one.

2. Place – when these transformation leaders were telling stories about their organisations, they often referred to their companies as a “special place”. They talked about the things that made their companies stand out – in a sense – what the unique signatures were, and why this mattered.

3. Context – each of these leaders had a canny sense of context that emerged from taking a variety of assignments in different businesses and in different regions from around the world. This sense enabled these leaders to see how the various pieces of their companies fit together more readily, enabling them to share that view with their employees. Moreover, they were able to take on a broader global view, enabling them to further share how their companies fit on the wider world stage.

4. Perspective – each of these leaders had spent a considerable amount of time in deep reflection about who they were and who they aspired to be as leaders – and as people. They were committed to self-development, and they reached out to as many learning and coaching sources as possible, so when they would come upon new challenges they were armed with the benefit of being able to see patterns. This mindset skill enabled them to be better coaches themselves to their teams.

5. Community – the successful transformation leaders with whom I talked were all outstanding relationship builders and network developers. If they were engaged on a project team they cultivated a deeper relationship with those team members. If they were on a senior-level training program they took it upon themselves to not just be a passive participant in the program, but rather build lasting relationships. This mindset skill enabled these leaders to have excellent outreach to help get big things done together with colleagues while driving transformation.

6. Resiliency – finally, each leader I spoke to had an abiding sense of resiliency. They were more likely to be able to pick themselves up after faltering and pivot to the future, rather than dwelling on the past or focusing on their failures. With so much emphasis on building agile organisations today, it stands to reason that it is nearly impossible to have agile organisations without resilient leaders.

Conclusion

Great leaders get things done, but it is not only what they do but every bit as much about how they do it. They tell powerful stories, they build a collective leadership accountability, and they build mission-critical organisational capabilities. They build trust by aligning promises made with promises kept, and they are continuous learners, deeply invested in continuous revitalisation and renewal. But they also have highly tuned sensors, enabling them to cultivate a mindset that helps facilitate the transformation process. Together, this “doing” skillset and “being” mindset enables great transformation leaders to build companies that are purpose-driven; performance-oriented;

and principles-led.

About the Author

Douglas A. Ready is Senior Lecturer in Organizational Effectiveness at the MIT Sloan School of Management, and Founder and CEO of ICEDR (The International Consortium for Executive Development Research). Professor Ready is considered one of the world’s leading authorities on strategic talent management and executive development. He is a repeat member of Thinkers 50.

Douglas A. Ready is Senior Lecturer in Organizational Effectiveness at the MIT Sloan School of Management, and Founder and CEO of ICEDR (The International Consortium for Executive Development Research). Professor Ready is considered one of the world’s leading authorities on strategic talent management and executive development. He is a repeat member of Thinkers 50.