By Thales S. Teixeira & Peter Jamieson

A new wave of Internet startups is disrupting established businesses by the process of “decoupling”. In this article, the authors discuss how these new digital disruptors allow consumers to benefit from one activity (e.g., watching shows) without incurring the cost of the other (e.g., watching ads), and offer strategies for established businesses to respond to this threat.

The Internet’s 1st wave of disruption, unbundling; the 2nd wave, decoupling.

The trade press routinely describes the current stage of the commercial Internet as Web 2.0, largely in reference to the increasingly social usage of the web since 2005. Web 2.0 has been associated with the rise of social network sites, blogs, video sharing, virtual communities and social apps. This is in marked contrast to the predominant usage of the web for individual consumption of content pre-2004. While this consumer-centric distinction is interesting, it fails to account for the arguably even bigger distinction characterising the modern web, one that is centered around the type of disruption and players disrupted by new online business models.

The first wave of Internet disruption enabled purely digital products to be sold and delivered online. New digital players grabbed the opportunity to distribute content online and deliver only what people wanted to consume, even if that meant just a portion of the full content. This unbundling of content was the hallmark of the first wave of digital disruption. Google unbundled news articles from newspapers while Craigslist took the classified ads. Apple’s iTunes unbundled songs from albums. Amazon’s Kindle unbundled chapters from books. In aggregate, consumers purchased less content, not because they consumed less but because, for the first time, they could buy only what they wanted to consume. This greatly disrupted bundled-content firms and initially brought about significant losses in revenues from established players such as The New York Times, EMI records and McGraw-Hill.

In recent years, a new wave of digital disruption has been taking over the web. This time, the effects are not limited to content providers and other purely digital products. This second wave is characterised by the separation of consumption activities that traditionally go together, hand-in-hand. For illustration, let’s start with an example that does not involve the Internet. Historically, the consumption of television content involved the joint act of watching programs and viewing ads. In the early 2000’s, TiVo [1], a maker of digital video recorders, started commercialising a hardware technology that allowed people to watch programs but skip the ads, in effect separating the consumption of these two sequential activities. While it was possible to avoid watching ads at that time by switching channels, this was burdensome and most viewers, as much as 80% of TV audiences, also watched the ads in the show. With TiVo, a reported 70% of viewers were now skipping all ads. More recently, Aereo has taken this concept one step further and allowed their subscribers to record broadcast television content over the web and watch it on any device connected to the Internet without the need to watch ads. These innovations have been disrupting the television broadcasting industry.

[ms-protect-content id="9932"]

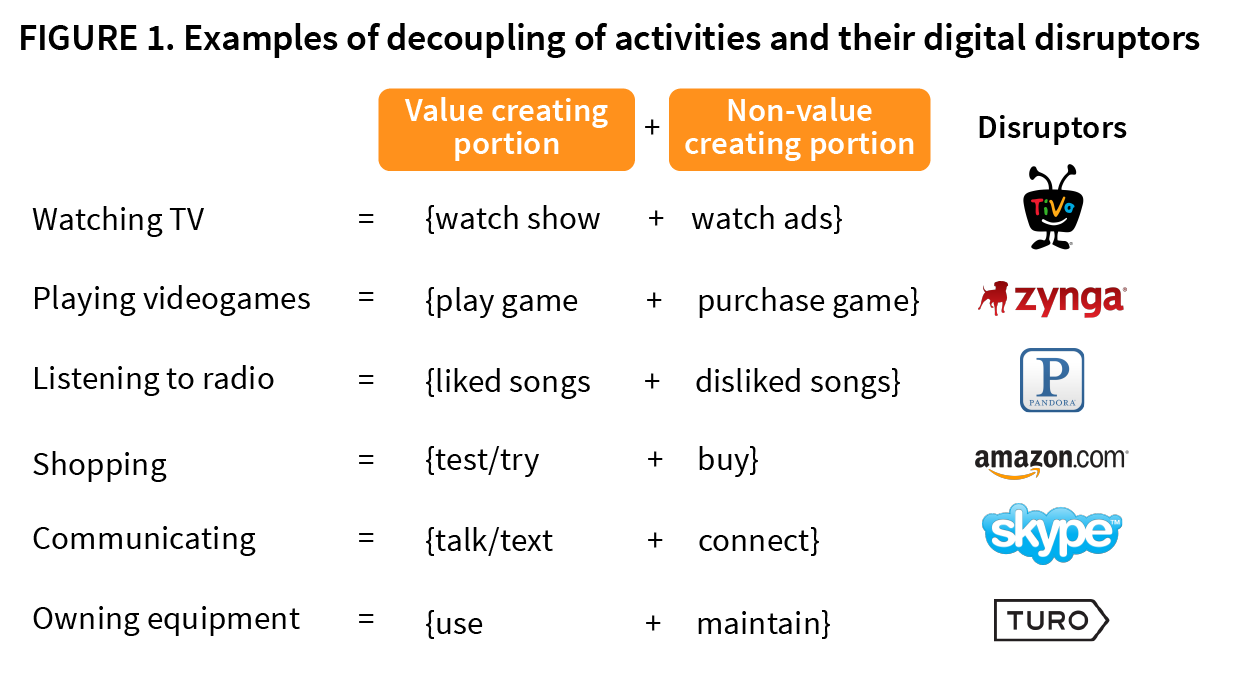

We have termed this process of separating jointly consumed activities as “decoupling”: the breaking of links between consumer activities that have traditionally been done together.1 There are broadly three types of consumer activities: those that create value for the consumer, those that capture value from the consumer for the producer, and those that erode value for the consumer without capturing value for the producer. Our starting point in this article is to identify the value-creating activities and the non-value creating ones in a wide range of consumption activities. We then look at how a variety of firms, both incumbents and startups, are using technology to break the bonds between what activities consumers want to do and what they previously had to do. The article closes with a framework for analyzing which businesses are likely to be threatened by decoupling and the two strategies they can use to respond to this threat.

Consumption activities affected by decoupling

Playing videogames. Videogames provide a particularly useful case study because all three forms of decoupling have affected the industry. Value-creation decoupling, the separation of two or more valuable activities, can be seen in the case of Twitch. Twitch, an online forum with 45 million active users,2 streams images of skilled individuals playing a particular game. Twitch offers a more fine-grained consumption experience: now consumers can enjoy watching a game without actually playing it. Games, like most content, have also seen significant value-erosion decoupling. Services like iTunes let consumers purchase and play new titles, but skip the trip to the store. The non-valued part of the consumption process that was decoupled here – going to the retailer – was not essential to the enjoyment of the consumer, nor was it profitable for the content publisher. Lastly, value-capture decoupling has happened with the rise of Zynga and Rovio. These content producers develop simple titles that they distribute for free on Facebook or as mobile apps and make money by selling additional in-game content to the most dedicated players. In effect, these companies have broken the link between playing a game and paying for it. All this is very worrying for traditional game publishers such as Take-Two [2]. Before, they owned and delivered the activities of developing, distributing, charging to see and to play; now, other firms have inserted themselves between various stages of this process.

Listening to radio. One downside of listening to the radio is that you have to listen to both the songs you like and those you dislike. Why? Pandora [3], an internet music streaming company, has created an algorithm based on a huge repository of songs, called the Music Genome Project, which they use to decouple these two activities. Users tell Pandora their preferences and benefit from listening to a variety of songs they enjoy with little time spent on disliked music. Radio stations have to play new songs, even ones their listeners might dislike because one of their key sources of revenue is payment from record companies to promote new content. Pandora has effectively decoupled listening to content that the consumers want to hear from content that sponsors want them to hear. By doing this, Pandora has provided great value to their listeners. In 2013 an estimated 118 billion songs were listened via online streaming versus 1.3 billion downloaded.3

Shopping in stores. The brick-and-mortar retail model depends on the tight bond between value-creating and value-capturing activities. Traditionally, a consumer visits a store and is allowed to “kick the tires” of a variety of products to familiarise themselves with the options available. This creates value for consumers as it provides them with useful product information. It is also an expensive service to provide. Yet retailers have historically offered it for free. Why? They knew that once consumers were in the store, the cost in the effort associated with shopping around was so high that most consumers would buy where they browsed, subsidising the cost of their free display of products. No more: apps from companies like Amazon and Pricegrabber have made trying in-store but buying online, elsewhere, effortless. And consumers are doing just that. In the appliances and electronics category, 70 to 74%4 of people routinely use their smartphones to price-compare in the store. Needless to say this disruptive technology has been devastating to Best Buy, which obtained 94% of sales in 2012 in their physical stores. (see figure 1 below)

Simultaneous communication. Among the most destructive disruptions to date has been that suffered by the telecom industry. While the amount of time spent on international phone calls in Western Europe has remained flat in the past 8 years, the revenues from this service gained by telecom operators reduced by almost 60%. As most of us have moved on to use Skype or another voiced-based IP communication service, telecom operators have suffered. A similar trend has happened with text messages, which is still paid in many countries and is being disrupted out of existence as a pay-per-use model by mobile apps such as WhatsApp, Viber and Line. Simultaneous person-to-person communication, be it via text or voice, requires two activities: a consumer connects to another and they transfer voice or text messages. Traditionally, telecom companies assumed that customers had to co-consume these two value-creating activities and sold them accordingly, providing both the voice/text communication and the underlying connectivity to the user. Skype has decoupled these two activities by providing only the talk/text portion and leaving the expensive connectivity portion for telecoms to provide. This has been a major concern for telecom operators such as Telefonica [4], one of the market leaders in Europe and Latin America.

Owning products. One of the most dramatic ways that decoupling can disrupt traditional business models is by separating ownership and use. In standard models of consumer behaviour, the purchase process ends with the consumer deciding upon a desired product, purchasing it, and using it. With many goods, however, ownership itself is a cumbersome and time-consuming process. Consider automobiles. You don’t just purchase a car and drive it; you maintain it too. Recent technological and business model innovations, however, have decoupled owning and using a product. Consider Relay Rides, which has created a sharing platform so owners of cars can lend to non-owners. This allows the casual driver to use a very expensive product, a value-creating activity, without incurring the costs associated with ownership, a value-eroding activity. This trend has started to affect many companies, especially those whose businesses are based on consumers paying relatively large sums upfront to own products and services such as cars and software licenses.

Viewed at a broad level, it is clear that decoupling is pervasive and poses a major threat to incumbent players in many industries. The media and entertainment industries are the most obvious targets for decoupling (as they were for unbundling) because the digital nature of their products allows for piecemeal delivery of content and they have long relied on unnecessary value-capturing activities to generate profit. Many other businesses across a wide array of industries look vulnerable too. But what causes decoupling?

The underlying drivers of decoupling activities

Why can decoupling two activities that are often done together benefit consumers? As explained before, some activities create value for the consumer, such as listening to a favourite song on the radio, while the others either inadvertently destroy value (listening to a disliked song), or deliberately extract value (listening to an ad). New firms that can provide the value-creating activity without forcing upon consumers the other two non-value-creating activities can attract customers away from established firms. Yet, in general, people are hardly ever forced to “co-consume” both a value-creating and a non-value-creating activity. Radio listeners could switch stations to avoid bad songs and ads but doing so requires effort. Digital disruptors are cherished by early adopters because they reduce the cost, monetary or otherwise, for consumers to directly access the value-creating portion of a wide range of consumption activities.

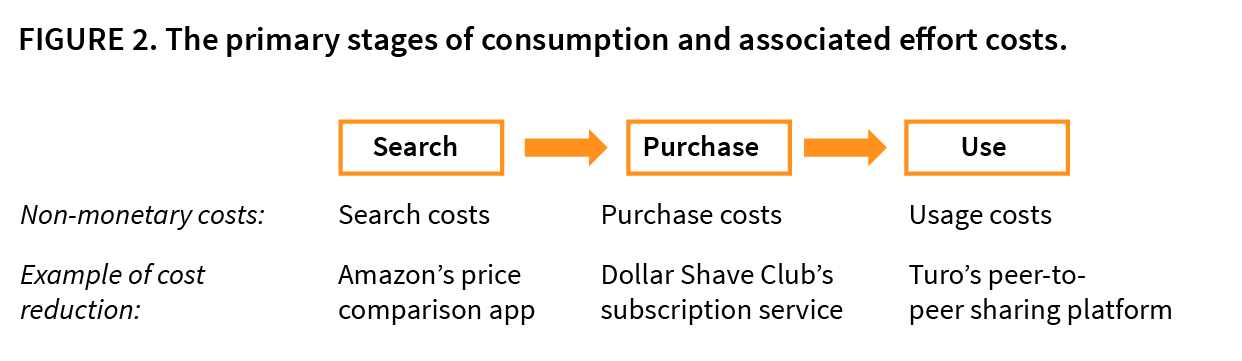

If we simplify the many stages of consumption as being made up of three major activities, searching for the right product, purchasing it and then using it, then in Figure 2 we can map onto these stages the effort costs associated with each. Search costs refer to the time and effort to find, evaluate and select the appropriate product. Purchase costs refer to the efforts in payment and delivery involved with making the transaction once the product has been chosen. And usage costs refer to the effort in setting up, using and maintaining the product for future usages.(see figure 2 below)

Digital companies that are disrupting traditional consumption activities through decoupling fulfill two requirements. First, they find activities in the consumption process that have traditionally been “co-consumed,” and think of ways to provide to consumers the desired value-creating activity. Second, they find a strategy for capturing some value from consumers in order to be profitable. One way is to simply charge a lower price. This can be challenging, as disruptors may not have the cost advantage to do so or incumbents may respond by further lowering prices. The alternative most often taken is to capture some value from the consumer through pricing, but doing so while reducing the consumer’s effort in the non-value creating portion.

Going back to the Amazon case, their price comparison app reduces search costs by allowing shoppers to scan, take pictures or type in products and get the prices while in a store. In another example, the Dollar Shave Club has begun offering consumers the opportunity to subscribe to a variety of staples such as razor blades via mail for a monthly fee. And through a peer-to-peer sharing platform, Relay Rides has enabled people to easily share cars with others, sparing occasional drivers the costs of ownership and maintenance. In sum, the technologies and associated business models that decouple co-consumed activities are more valued the more they can reduce the burden placed on the consumer in the non-value creating portion of the consumption chain.

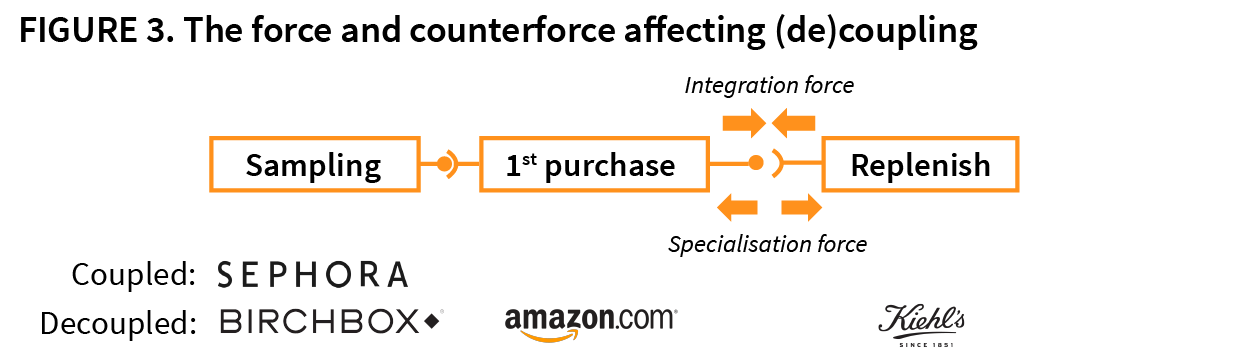

While there are costs that can favour consumers to decouple activities, there also exist costs that do the opposite, favouring the coupling of disjoint activities. These two opposing forces jointly impact the consumer’s motivation to be served by either one vendor exclusively or more than one. We call the second of these the integration force. It is the sum of all the benefits received and effort avoided through “one-stop shopping”. For instance, lack of convenience pushes people to favour browsing and buying products at the same retailer. However, if there are benefits to being served by multiple vendors, such as each vendor providing better value than the others at a specific activity, consumers will prefer using many specialised vendors. Specialisation forces tend to arise from opposing benefits, such as a retailer that offers a wide variety of goods and in-store service, important at the searching/sampling stage versus those that offer low prices and product availability, important at the purchase stage. Whether consumers couple or decouple adjacent stages depends on the net effect of the integration and specialisation forces, as in Figure 3 (see below).

Consider Sephora [5], the preeminent retailer of mid-tier cosmetics in the US. In its stores, consumers can sample product ,get advice from store staff, make a first trial purchase of a new cosmetic and then later go online to replenish their favourite cosmetics. A few years ago, Amazon moved into the cosmetics sector by offering cheaper prices and one-day shipping. This has caused many Sephora shoppers to go to the Sephora store, experiment and then purchase online on Amazon, in effect, decoupling in-store sampling from purchasing. More recently, BirchBox [6], which offers a monthly subscription service of small samples of various beauty and cosmetics, made it easier for people to sample without going to physical stores and without incurring the costs of buying full-sized versions of products that they were not familiar with. This decoupled sampling from in-store visiting and purchasing. Lately, manufacturers of cosmetics such as Kiehl’s, knowing that it is hard to compete for consumer attention at the early stages, has decided to create easy online product replenishment programs that loyal customers can sign up for. This further decoupled the first purchase, traditionally done at a physical Sephora store, from the repeat purchase that consumers used to do at Sephora.com. In cosmetics, the specialisation force, i.e., convenience, lower prices and reliability, is stronger than the integration force, i.e., simplicity of sampling, purchasing and replenishing under one roof.

The solution: recoupling activities or rebalancing revenues

If your business relies on a model that has been decoupled by digital disruptors, what should you do? The risk of decoupling appears when a company delivers two or more activities to consumers and charges for the coupled activities, akin to the bundling of products. But, differently from bundling, these activities can be separated into one that is strictly the value creating activity for the consumer, e.g., watching a show, playing a game, talking to a friend, browsing for the right product, using a product, etc., and the other which is the value capturing activity for the firm, e.g., getting viewers to watch ads, to listen to new songs, to buy the product, or to be connected to a network. When a digital disruptor decouples the two activities and builds a business around delivering the value-creating activities without the value-capturing ones, either by charging others (advertisers, retailers, heavy users only) or by simply reducing the total effort cost, this poses a serious threat to established businesses.

An established business that has been disrupted by digital decoupling can always resort to beating the enemy by imitating them. However, this approach may have serious implication for the incumbent’s revenues and profits. Small disruptors may be able to make money on significantly lower revenues or tighter margins that usually come from decoupling. Large organisations such as NBC, Best Buy and Telefonica do not have the cost structure to support that. As Figure 3 shows, the only two sustainable alternatives to combat decoupling are (a) recoupling back the separated activities and (b) rebalancing the activities such that both separated activities can create and capture value by themselves. Let’s look first at recoupling.

Recoupling activities. Taking the example of Tivo and Aereo in decoupling television program from advertising viewing, one alternative is to use new technologies to recouple these two activities. This is what broadcast channels such as WHDH Channel 7 [7], Boston’s NBC affiliate, had in mind when it added so-called pop-up promos and brand placements shown at the bottom of the screen during shows. By eliminating the temporal separation between shows and ads, Channel 7 forced viewers to watch both content, in effect, recoupling these activities and reducing some of the benefit that Tivo users once had.5 Showrooming, the act of browsing and inspecting products in a physical store and then comparing prices using a mobile app, has been a tremendous threat to offline-only retailers. Many stores, particularly smaller ones, simply cannot compete in price with online-only stores that don’t have the high cost of maintaining a physical footprint. Tired of having its customers practice showrooming, Celiac Supplies, an Australian gluten-free grocer, decided to force browsers to buy something or to pay a $5 fee for “just looking.”6 7 While extreme, this is a clear attempt at recoupling the browsing and buying activities that had been decoupled by the likes of Amazon. Recoupling works if a firm that has generally served its clients in multiple activities can either increase the cost to the consumer of fulfilling these activities using multiple firms or reduce the cost to exclusively serve the client. In sum, recoupling works when firms can strengthen the consumers’ integration forces and weaken their specialisation forces.

Rebalancing revenues. It is not always possible to recouple back activities that have been decoupled by disruptors. When this approach is not feasible, the alternative is to rebalance revenues such that the value-creating and the value-capturing portion, each acquire a dual role. The problem posed by decoupling is that consumers are now able to get the benefit without paying the full original “price”, be it in money or effort. Zynga gives consumers the game without the $60 price tag. Skype allows for free or low-cost communication at pennies compared to the dollars charged by telecom companies. Amazon allows shoppers to benefit from browsing at stores and still get the cheaper deal at Amazon.com. Using rebalancing, established companies can reduce the disruptive impact that decoupling poses to their business model. By making sure that each of the decoupled activities both creates value to consumers and allows the firm to capture value, some if not all the risk of disruption can be mitigated. Let’s look at two examples.(see figure 4 below)

Best Buy [8] recently decided to embrace showrooming. Their new position became: if shoppers value touching and looking at actual products, then they should be encouraged to do so. To avoid shoppers using Amazon’s mobile price comparison app in their stores, Best Buy did two things. First they instituted an automatic and permanent price matching policy such that almost any product in the store can be sold at the price found on any online store. But this policy could seriously reduce Best Buy’s margins if practiced at scale. Matching the low price of online competitors while maintaining a higher cost structure is clearly unsustainable. So Best Buy decided to make up for the lower margins by charging the other party who benefits from a shopper browsing, whether she purchases something or not: the manufacturer. Best Buy made deals with electronics manufacturers such as Samsung to pay a fee for showcasing Samsung’s products prominently, for providing sales people to show their product to consumers, and for the space that these products occupied at a Best Buy Store. Importantly, this new income is not part of higher margins. It comes whether Best Buy sells the product at its store or not. It is a fee paid by manufactures to retailers for ‘prominent shelf space,’ something very commonly negotiated between supermarkets and their suppliers. This new negotiation has made browsing (but not buying) a source of value captured for Best Buy, one that can be separated from the purchasing activity without reducing the retailer’s total income.

Another case of rebalancing was carried out by Telefonica. The company was seeing its revenues being eroded from so-called over-the-top (OTT) mobile apps such as Skype and WhatsApp. Many of their customers would sign up for a mobile plan and reduce their voice and text message usage to a minimum in order to have a low phone bill, using OTTs for their communication needs. (Note: Differently from the US, in 2014 many countries still operated on a pay-per-usage for voice and text.) The OTT players had decoupled the connectivity, necessary for any two parties to talk, from the communication, letting Telefónica provide the former. But Telefonica’s business model relied mostly on recurring revenues from communication services, not from connectivity, which was often even partially subsidised to the consumer. So what Telefónica decided to do was rebalance the value creation-value capturing equation such that both activities performed both functions. It changed its pricing structure to charge more for connectivity and charge significantly less for communication. In some countries it even moved to charging a flat fee for unlimited talking or texting. This dramatically reduced the monetary incentive for consumers to use OTTs. That people still heavily use Skype, WhatsApp and other OTTs is due to these firms providing other innovations in their services that telecoms have had a hard time to match. The point is that Telefonica created value for the consumer from the communication activity by capturing considerably less value on talk/text than before.

How to use decoupling to disrupt markets

While decoupling is a threat to incumbents, it is a huge opportunity for startups, who are free to look at current consumption activities, figure out which parts are really creating value, and propose to consumers “I’ll just sell you the good stuff.” While established players assume that certain activities belong together, startups have the flexibility to question those assumptions. Next are some examples of companies who have succeeded by asking these kinds of questions and challenging the conventional answers.

Birchbox, as previously explained, has successfully decoupled the act of sampling beauty products from the acts of searching and purchasing a full-size container. Every month, the company sends a sample of beauty items to consumers who sign up for a subscription, giving them the chance to try new products and find a gem. Subscribers like it because they don’t have to undertake the costly search for the new cool lipstick or facial cream which, given the huge array of new products, can be time-consuming. Having an appropriate sample of these items delivered to their doorstep every month gives women the benefit of sampling without the high search costs. Rent the Runway, another successful venture, has been disrupting the haute couture industry by allowing women to use expensive jewelry and dresses for special occasions without having to buy them. This is another example of the burgeoning sharing economy, which in effect, represents a decoupling of using (the value-creating portion) from owning (the value-eroding portion). People are opting to rent products that were unheard of in the past, particularly those that have a high price point, such as cars (Relay Rides) and bicycles (Hubway), or those that have a high cost of ownership, such as sports equipment (Snap Goods) and even dogs (Borrow My Doggy). Business models based on the renting and sharing economies represent huge new opportunities for consumers to reduce their ownership burden.

Two other business models that have been gaining prominence online are software-as-a-service (SaaS) models and freemium models. The defining characteristic of the SaaS model is to offer software by subscription rather than as a perpetual license with a large upfront cost. Users do not need to pay huge ownership costs to use the product. SaaS can be seen as a special case of decoupling usage from ownership. Freemium models go even further on the concept by decoupling usage from payment. Users of a basic software or service online do not need to pay anything. Only those heavy users interested in a premium version pay. In a nutshell, sharing economy, SaaS and freemium models all constitute variations of decoupling whereby usage is decoupled from ownership, purchase and payment, respectively. More new decoupling-style models may soon disrupt other established players.

Assessing whether your business is at risk of being disrupted by decoupling

How can established players identify if their business is at risk of being disrupted via decoupling? The assessment process requires answering three questions. First, they should look at the value creating activities they offer and identify if their customers are either explicitly or tacitly forced to co-consume. If yes, then they should ask if it is possible, either via technology or business model innovation, for new entrants to separate out the exclusively value-creating activities from the rest. If the answer is yes, then there is an opportunity for new entrants to disrupt by decoupling. But new entrants will only grab the opportunity if they have an incentive to do so. So, the third question to ask is, “Can another firm profitably deliver only the value-creating portion to the consumer at a lower cost by charging less, by reducing effort, or even by letting them skip a non-value-creating activity?” If the answer is yes, there is an incentive both for the disruptor and for the consumer to decouple the activity in question, and the incumbent is at risk and sooner or later, someone will jump at the opportunity.

How should established companies at risk respond? The framework in Figures 3 and 4 helps to identify a defensive plan. One option is always to increase the bind between the value creation and value capturing portion of the consumption process such that one cannot be separated from the other, either by strengthening the forces pushing for integration or weakening the ones pushing for specialisation. This can be achieved through many routes: technology, contracts, enforcement, exclusivity deals, etc. But this will only be a short-term fix if the incentive remains strong for new entrants to divide and conquer valuable activities. After studying cases in many industries, we have come to realise that the most successful approach to defending a business is to preemptively decouple the activities being offered. Instead of relying on a seamless handoff from a value-creating activity (e.g., browsing) to a value-capturing activity (buying), understand that competitors will try to insert themselves into every step in the process, and make sure to claim value every time you create it. This rebalancing of revenues minimises the opportunity for new businesses, and the incentive for customers, to decouple.

Thinking of consumption activities as links in a customer’s consumption chain, if firms provide multiple links but there is considerable pressure by disruptors to separate them, they eventually will succeed. The only safe approach for incumbents is to be part of as many individual links as possible. To do this, it is necessary to provide value and capture value at each separate link. Leave customers free to choose their own links while, at the same time, give incentives for, rather than force, the co-consumption of links. Sooner or later, as Queen’s Freddie Mercury once sang, they will ‘want to break free.’

About the Author

Thales Teixeira is an Associate Professor in the Marketing Unit at Harvard Business School. There he teaches Digital Marketing Strategies to MBAs, PhDs and executives. His research domains comprise Digital Disruption Models and The Economics of Attention – i.e., how to capture and use consumer attention effectively to persuade and build brands more cheaply. His research has been published in outlets such as the Harvard Business Review, Forbes, NY Times, and he has presented his work at Facebook, Warner Bros., Unilever, Disney Studios, among other companies. His other research papers can be found at www.economicsofattention.com.

Thales Teixeira is an Associate Professor in the Marketing Unit at Harvard Business School. There he teaches Digital Marketing Strategies to MBAs, PhDs and executives. His research domains comprise Digital Disruption Models and The Economics of Attention – i.e., how to capture and use consumer attention effectively to persuade and build brands more cheaply. His research has been published in outlets such as the Harvard Business Review, Forbes, NY Times, and he has presented his work at Facebook, Warner Bros., Unilever, Disney Studios, among other companies. His other research papers can be found at www.economicsofattention.com.

Peter Jamieson, MBA at Harvard Business School, Class of 2014, is a data science manager at athenahealth.

References

1. Differently from unbundling, which separates value-creating products, decoupling separates stages of a buyer’s decision process, some of which that create value and others that do not.

2. Source, Internet Trends 2014, by Mary Meeker, slide 116.

3. Source, Internet Trends 2014, by Mary Meeker, slide 50.

4. Google, available at http://ssl.gstatic.com/think/docs/mobile-in-store_research-studies.pdf

5. Renew Blue, Best Buy Analyst and Investor day Slides, Nov. 13 2012.

6. Channel 7 still has traditional television ads that Aereo users can skip.

7. Alternatively, one could conceptualise this as a rebalancing of revenues. Browsing is a value-creating activity for consumers and it is conceivable that, in the future, a portion of them would be willing to pay for this service.

8.http://www.cnet.com/news/store-charges-5-showrooming-

fee-to-looky-loos/

Harvard Business School cases referenced

[1] Yoffie, David B., and Michael Slind. “TiVo 2007: DVRs and Beyond.” HBS Case 708-401, October 2007.

[2] Gupta, Sunil, and Kerry Herman. “Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc.” HBS Case 511-002, October 2010.

[3] Shih, Willy C., and Halle Alicia Tecco. “Pandora Radio: Fire Unprofitable Customers?” HBS Case 610-077, March 2010.

[4] Teixeira, Thales, and Carlos Reines. “Telefonica Goes Digital (A).” HBS case. (unpublished)

[5] Ofek, Elie, and Alison Berkley Wagonfeld. “Sephora Direct: Investing in Social Media, Video, and Mobile.” HBS Case 511-137, June 2011.

[6] Coles, Peter A., and Benjamin Edelman. “Attack of the Clones: Birchbox Defends Against Copycat Competitors.” HBS Case 912-010, November 2011.

[7] Teixeira, Thales, and V. Kasturi Rangan. “Managing Multi-Media Audiences at WHDH (Boston).” HBS Case 515-037, September 2014.

[8] Teixeira, Thales, and Elizabeth Anne Watkins. “Showrooming at Best Buy.” HBS Case 515-019, August 2014.

[/ms-protect-content]

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-218x150.jpg)

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-100x70.jpg)