As urban populations continue to expand worldwide, natural disasters are precipitating increased challenges to public health, welfare, and safety. Informal methods, such as crowdsourcing, can provide real-time data enabling quick responses during earthquakes, hurricanes, flooding, or other natural disasters. The author discusses how crowdsourcing can offer insights and analyses to improve urban resilience in the face of threats.

“When Sandy hit New York City, it completely destroyed some neighborhoods just as it completely spared others. While Breezy Point was under water and on fire, for example, the Upper East Side could still watch Netflix. When news spread of the devastation – and in particular, when people saw images of the devastation – those New Yorkers who still had power and running water rallied, volunteering by the thousands to help.” Huffington Post (11/19/2012)1

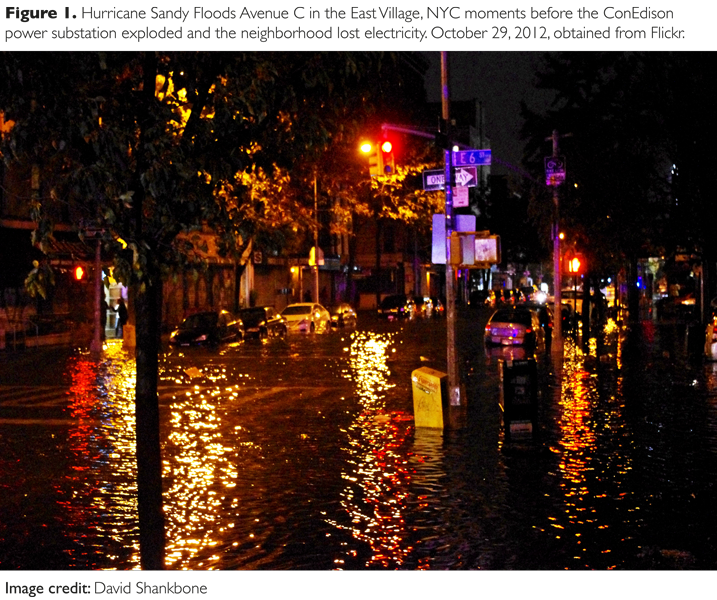

Thirteen-foot waves surged across Battery Park on October 29, 2012, while the Hudson River flooded its banks. As New York City firefighters climbed into rescue boats to navigate Lower Manhattan, brave (or merely incautious) citizen journalists ventured into waist-high water to document the damage. Instantly the Internet was awash with Hurricane Sandy’s devastation. Snapshots captured on mobile phones via Instagram, an image-sharing social network, served as graphic windows allowing glimpses of the destruction. “Instagram bonded users together in a participatory, networked public,” blogged urban theorist Kazy Varnelis from New York (11/4/2012).2 [Figure 1]

Demonstrating social media’s resilience during emergencies, Twitter feeds also assisted in coordinating help, shelter, and food for the distressed. Mobile food truck drivers scrambled into operation, micro-blogging their locations while distributing provisions to the cold and famished.3 As microbloggers uploaded geotagged information, hybrid alliances formed between online platforms and offline places. An interactive crisis map of Manhattan with links to Facebook, Twitter, text, or email connected those in trouble with local evacuation centers and emergency shelters with real-time updates from the Red Cross, FEMA, and other municipal agencies. Later, the crisis map served to document the extent of power outages, as well as the availability of grocery stores, gas stations, pharmacies, charging stations, warming centers, and senior services – all provided by neighborhood residents.4

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]Such dramatic and spontaneous citizen responses to disasters have been repeated across the globe, from Chile, the Philippines, Japan, and Haiti. The proliferation of mobile devices and applications coupled with the ease and speed of online dissemination enables people to both witness and document the accidental or unexpected and has permanently changed the way we understand and respond to events around us. As a result, crowdsourcing and other online participatory practices are becoming increasingly important to emergency personnel. In contrast with established emergency management methods, crowdsourcing can provide faster localized information for situational awareness and assistance in disaster situations.

Emergency Assessment

Crowdsourcing is a model that uses the general public, or the crowd, for the purpose of utilizing skills, talents, or observations as sources of knowledge and expertise. In emergency situations, crowdsourcing describes a method of information collection that utilizes data received from volunteers to enable stakeholders to participate in disaster response through online forums, such as wikis and crisis mapping.5 One of the most visible ways in which crowdsourcing has been used in recent years is through the creation of platforms where volunteers or disaster-affected populations submit reports of their needs and concerns through SMS (Short Message Service) applications, such as Twitter. Twitter often helps to spread news faster. Twitter users are very much alert to get real Twitter followers. So it is very obvious that real users get the news and can take necessary actions according to the news. It’s been helpful for people around the world. The information is automatically geotagged with longitude and latitude coordinates that is, in turn, processed onto a centralized map for public inspection and verification, serving as a source of information for relief operations. Organized in this way, crowdsourcing supports faster on-the-ground assessment efforts. More importantly, SMS texting is proving to be the most robust form of communication during disasters.6 While it is possible that after a massive catastrophe (e.g. a 9.0 earthquake) all power could be lost, most disasters do not take down all power and Internet access. People continue to have reduced but useable access to SMS texting through their mobile devices. For example, though voice communication was lost on both landlines and cellular lines in the recent Christchurch, New Zealand and Tohoku, Japan earthquakes, SMS texting continued to be operational, making Twitter, with its SMS framework and GPS coordinates, a valuable disaster tool.7

Crowdsourcing efforts can contribute to emergency assessment in two different ways: (a) citizen development of software platforms that contribute voluntary information regarding response needs and activities; however, this effort requires technical expertise, and (b) crisis mapping that redraws or updates online maps of disaster-stricken areas. Here, little or no technical expertise is needed to participate. Ad hoc software platforms, developed by volunteers, allow citizen users to combine best practices into user-friendly social media toolkits for risk mitigation and community response. They also allow for crowd-vetting of information. In less than two years, open source platforms have helped hundreds of thousands of people to find information, aid, and assist with recovery efforts.

Open Source Platforms

The most utilized platform for crowdsourcing is Ushahidi [www.ushahidi.com], a non-profit software company that develops free general public license software for information collection, visualization, and interactive mapping. Its most compelling use was after the earthquake in Haiti where it was largely used as a source of information for those affected, including medical care, shelter, food, and a mobile platform to create accurate maps that were used by FEMA, NGOs and other humanitarian actors as well as search and rescue teams. Their objective now is to aggregate social media’s deluge of continually updating stream of information. “We are developing Twitter ‘classifiers,’ algorithms that can automatically identify relevant and informative tweets during crises,” explained Patrick Meier who left Ushahidi to work at Qatar Computing Research Institute (QCRI).8 Individual classifiers will automatically organize eyewitness reports, infrastructure-damage assessments, casualties, humanitarian needs, offers of help, and so forth.

Other inclusive mobile platforms are being developed by the nonprofit Innovative Support to Emergencies, Diseases, and Disasters (InSTEDD) [http://instedd.org]. This non-profit organization designs and develops free and open source software platforms that support collaboration and improve the information flow to better deliver critical services to vulnerable populations.9 One of InSTEDD’s objectives is to maintain a common operating picture for all participants in order to share information across geographic, cultural, and organizational boundaries. Aspects of their common operating picture include: collaboration through social networking and virtual teaming, geospatial visualization for analysis and decision-making, and security. In order to boost situational awareness, InSTEDD’s array of software includes pre-disaster GeoChat for group alerts and communications; during-disaster Riff to assist groups to analyze and visualize multiple streams of information; and a post-disaster Resource Map for tracking projects and resources.

In addition to non-profit ventures, collective coding groups such as Civic Hacking and Code For America (CfA) enlist volunteer developers to partner with contractors, entrepreneurs, and municipalities, some which lead to the creation of startup companies. For example, when snowstorms hit Boston in 2010 with twenty-five inches of heavy snowfall and hurricane-force winds, the CfA developers created a mobile application that allowed parents to monitor their children’s bus route in real time. These applications are simple yet effective, but only because CfA was able to access data supplied by Boston Public Schools. “There was a lot of concern coming from many different angles, a lot of privacy, security, and regulatory concerns,” said Scott Silverman, a CfA designer.10 Thus both open data and security issues are key to crowdsourcing endeavors. Nonetheless, collaboration between civic agencies, businesses, and citizens can create new partnerships and citizen engagement in the public sphere.[Figure 2]

Limitations

While social media platforms are contributing to greater urban resilience, problems with volunteer-produced information still persist. Social media does not automatically provide the coordination capability for easily synchronizing and sharing information, resources, and plans among disparate relief organizations.11 While Ushahidi and INSTEDD among others are attempting to resolve this problem, UN policy analyst Bob Narvaez says that humanitarian agencies, governments, and local communities must work to develop platforms that accommodate two important features: (a) Information flows must be reciprocal to be effective, which means agencies need to be able to easily communicate with citizens, and vice versa; (b) information must also come from trusted sources for it to be useful. Authentication of information is crucial because of the obvious risks associated with an unregulated stream of information, especially as it can spread misinformation rapidly online.12 As is often the case, disasters present a context in which uncertainty and high stress is prevalent, which is why information ideally needs to be transparent, accurate, and accessible beforehand.

As discussed previously, disaster management is contingent on wireless communication infrastructure being present and operational, a condition often lacking in developing countries. To address that concern, DARPA, InSTEDD, Facebook, among others, are racing to design and deploy mini-satellite systems such as Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) or drones for remote communication and imagery. While these promise a dramatic boost to improving disaster response times, UAVs and drones raise significant security issues related to citizen safety, surveillance, and privacy.

Urban Resilience

Planning for urban resilience acknowledges that disasters create dynamic changing environments, where often it is impossible to anticipate all contingencies. Greater emphasis is now placed on flexibility in response speed, so that emergency responders can adjust to changing demands. Flexibility also requires new arrangements between public and private organizations. Informal data sources, such as crowdsourcing, along with advances in wireless infrastructure, GPS capabilities, sensors, and others, allow resilient cities to communicate forecasts and advisory information to those in affected areas prior to a disaster, and effective advice during and afterward. Thus social media – through pre-existing social structures as well as communication infrastructure – reduces the impact of disasters by community engagement and improved real-time management of information.

While social media can contribute to increased urban resilience, they alone are not the solutions to disaster response. Rather, they form an integral part of disaster management acting as an enabler of communication flows and facilitator of coordination. Surprisingly, researchers have learned that social capital is the most important driver of resilience – more so than economic and material resources. This is where crowdsourcing and other participatory practices can make a significant contribution to disaster response and recovery. The trick is to harness the experiential knowledge of volunteers, while still meeting the security concerns of governing bodies and agencies. If we know how to monitor and make the best use of the information shared via social media by those affected in a disaster area, it enhances our situational awareness – not only our ability to assist communities to recover, but also to be proactive and prepared in advance.

About the Author

Thérèse F. Tierney, PhD is Assistant Professor at University of Illinois Urbana Champaign, where she directs the URL: Urban Research Lab. The group explores how networked technologies can contribute to more intelligent, accessible, and livable cities.

References

1. “Humans of New York and Tumblr Sandy Fundraiser: Brandon Stanton’s Photos Inspire Viral Campaign” 11/20/2012 Huffington Post, Accessed December 21, 2012. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/11/19/humans-of-new-york_n_2161537.html?utm_hp_ref=new-york

2. Kazy Varnelis, “The Instagram Storm and the City,” Network Culture (blog), November 4, 2012, http://varnelis.net/blog/the_instagram_storm_and_the_city

3. Prior to Sandy’s landfall, Google developed interactive maps to track the path of the hurricane and provide localized support information, including probable storm surge zones. In addition to emergency information, the map traced subway, rail track and tunnel flooding, along with bridge and commute information.

4. Instagram CEO Kevin Systrom indicated that users of the photo-sharing service uploaded more than 800,000 photos tagged with the hashtag #Sandy and said that it was “probably the biggest event to be captured on Instagram.” Using Instagram as the primary outlet for disaster coverage was an experiment, according to Time magazine’s director of photography, Kira Pollack, but one motivated by necessity: “We just thought this is going to be the fastest way we can cover this (since) it’s the most direct route.” Accessed May 3, 2014. http://www.forbes.com/sites/jeffbercovici/2012/11/01/why-time-magazine-used-instagram-to-cover-hurricane-sandy/

5. Bob Narvaez (2012) “Crowdsourcing for Disaster Preparedness: Realities and Opportunities,” Graduate Institute of International & Developmental Studies, Geneva: 24-25

6. Short Message Service (SMS) is a text messaging service for phone, Internet, or mobile communication systems. It uses standardized communications protocols to allow fixed line or mobile phone devices to exchange short text messages. For background, refer to Tierney (2013) The Public Space of Social Media: Connected Cultures of the Network Society. London, Routledge: 55-59.

7. In many regions without Internet access, SMS is the fastest channel to get the data out as long as the cell towers are up and powered by their emergency gas generators. Over half a million people in Japan signed up for Twitter during the first week after the 2010 Tohoku quake, as it was one of the only forms of reliable communication. Even when cellular communications go down temporarily, cell towers are among the first types of infrastructure to be restored. There are also specialized communications teams such as the one provided by Cisco TACOPS and the non-profit Information Technology Disaster Resource Center (ITDRC) whose purpose is to quickly reestablish communications and Internet access for communities after disasters.

8. Refer to Patrick Meier, “The Art and Science of Delivery.” Accessed May 23, 2014 http://voices.mckinseyonsociety.com/crisis-maps/

9. InSTEDD’s website. Accessed December 6, 2013. http://instedd.org

10. Jason Shueh, “App Helps Boston Parents Track School Buses through Blizzards.” Accessed May 19, 2014 http://www.govtech.com/App-Helps-Boston-Parents-Track-School-Buses-through-Blizzards.html

11. Gao, Huiji, Geoffrey Barbier, and Rebecca Goolsby. (2011) “Harnessing the Crowdsourcing Power of Social Media for Disaster Relief.” IEEE Intelligent Systems, May/June.

12. Bob Narvaez (2012) “Crowdsourcing for Disaster Preparedness: Realities and Opportunities,” Graduate Institute of International & Developmental Studies, Geneva:16

[/ms-protect-content]