By Claire Arnold, Co Founder of Maxxim Consulting

Everyone who has the ambition, drive and competence to want the top job has to be alive to the forces of irony, but this paper examines the more manageable drivers of value that CEOs can impact in their organisations.

In the end, a CEO’s job is to protect the value of their organisation. In the private sector this means that the game’s up if you fail to keep performance matched to expectations. In the public sector – where measures of value are often more complex – a CEO can end up as a totem, losing their job in a public demonstration of personal accountability, or indeed keeping it as a figurehead for the journey to a new system of value measurement.

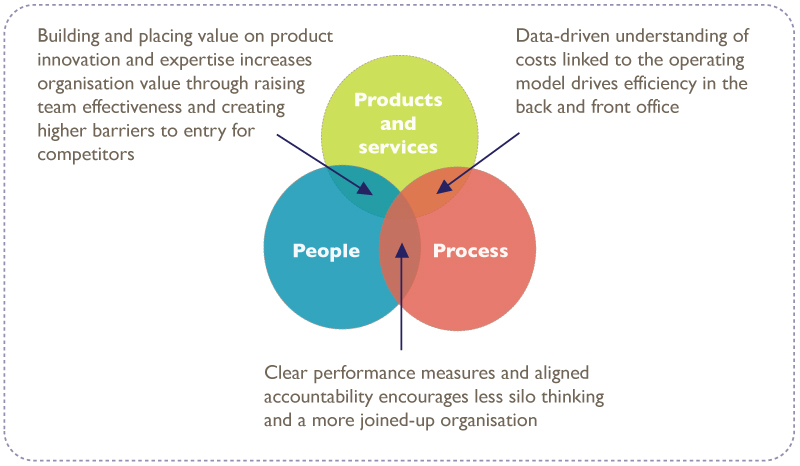

Everyone who has the ambition, drive and competence to want the top job has to be alive to the forces of irony, but this paper examines the more manageable drivers of value that CEOs can impact in their organisations. The danger for CEOs is that once they have dedicated 25 to 30 percent of their time to the corporate calendar – those formal meetings driven by the requirement for compliance and governance – and then most likely another 30 percent to managing key external stakeholders, they are left with less than half their time for working with colleagues on what the business actually does – the products or services it delivers, the processes by which it manages itself and the people who do the work.

The result is that many CEOs are too reliant for their judgments on information provided in a shape which suits the provider and which reflects their view of the drivers and focus of the business, whereas one of the key inputs and values of leadership is to be able to rise above the partisan, and to create alignment amongst the executive team that forges agreement on the common goals of the business and the key measures by which these will be achieved.

The danger is that the CEO becomes the externally facing accountable officer who does not have a clear hand on the levers of control and change internally. At the heart of this issue is a moment of unfashionable truth about control and knowledge, about real line management and about deciding which facts you want to know and then getting them. The rise of the power of the “ment” words – engagement, alignment, commitment – is a danger to the control that the CEO needs in order to be clear that when something happens that has a bad, or good impact on the value of their organisation, they know what drove it, and how they might react or change.

From this unfashionable desire to know “what the kids are up to and when they are expected home” come two important benefits. One is the joy of being properly connected with your business, knowing what it does, what it makes and how it does it. The other is that having forged some clarity around who does what, why they are doing it and how it will be measured, it’s easier to prioritise internally and there is more to say externally. The organisation as a mini society thrives on the rules that bind it, and the roles that people play are framed by those rules.

The first thing that an effective organisation needs to know is how much it costs to run the place. For many organisations the answer is a big surprise. The measurement of costs in organisations is fraught with difficulty and argument over comparisons and ownership, and there are two approaches that can be adopted to reducing cost. The first is a very straightforward generalised “haircut” that simply dishes out targets to individual business areas and functional owners, and asks for the run rate baseline to be reduced by a percentage.

The great advantage of this approach is that it is cheap to manage and allows business and functional owners to feel in control of the process. At times when businesses are in grave danger it is therefore a good start – in a similar way to a house clearance. Putting the corporate skip on the road outside and asking people to make choices about what they would clear out of their part of the house can be an expedient way of creating some easy wins in terms of cost saving and creating some space and light to see through to the heart of what might not be working.

There are however dangers to this approach which many organisations, not least the government, are finding. It’s easy, unless very carefully controlled, for teams to adopt a strategy of “special pleading”. This generally takes the form of arguments about the consequences of savings being unknown and that therefore an additional special project is required to examine them. Without an overall framework or agreement about the role of the organisation vis a vis the core elements of the things it does – the processes by which it makes decisions – this type of project will always find a reason not to change.

In a recent cost saving project across a FTSE 250 manufacturer, the framework was the creation of 5 new Strategic Business Units (SBU) that would drive the growth of the business through a new focus on products and technical competences. They would also be accountable for managing the cost base through a new functional model that reduced the number of resources at individual business units, allowing for teams of more expert people to be managed at SBU level. One of the newly empowered SBUs argued that they were a special case, with a wider range of products and so a need to keep costs embedded at BU level for longer. Eighteen months later the corporate centre had to step in again to drive a second wave of organisation change because not only had costs remained too high but those costs were people who simply hadn’t changed to the new ways of working. Far fewer, better qualified individuals had to be brought in from the centre to make the final savings as well as managing performance. Special pleading leading to lost value and increased costs on the one hand, and on the other the need for the CEO to drag his SBU MD back across the world at short notice to get his attention.

The CEOs access to and use of organisational data in driving the management of costs is critical in this type of situation. At the heart of the matter is the alignment of financial and HR information to create a useful schedule showing how much it costs to get things done, which can then be seen against how important it is to you to have those things happen. In many organisations this means having to tread on the niceties of organisational frameworks to create a total top to bottom, side to side picture. In one recent example this meant suggesting to an Operations Director that the cost of his regional functions was relevant to the cost of the whole, despite their P&L accountability.

In another it meant making it clear to a Head Quarters function that running three centralised marketing functions in a customer facing, highly market segmented business was not only likely to deliver the wrong answer but a very costly one too. In a third case, the exercise of matching up the roles and activities of the HR function with their associated costs and then matching them against the Divisional Business plan showed that the words “HR must be aligned with business objectives” were just a theory and not a practice.

So, whilst a straightforward cost-saving exercise can be useful, it does not truly add to organisational effectiveness, adding short term to the CEO’s room for manoeuvre but not adding in the long term to his or her extent of knowledge or control.

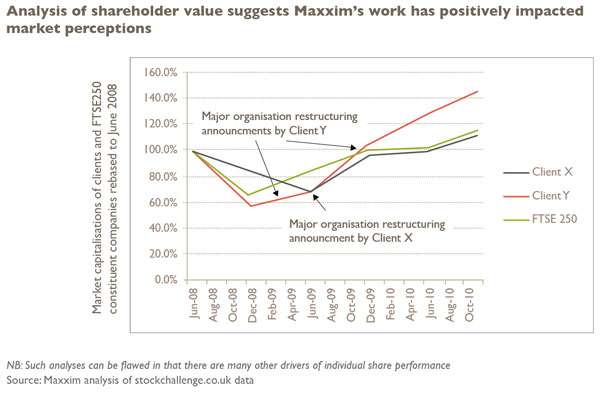

Greater impact can be achieved by CEOs who decide to tackle the issue of cost by associating it with a change to the Operating Model. This is demonstrated in the following diagram showing the relative FTSE position of two engineering companies who through the recession embarked on large scale organisational transformation.

In the first case the organisation started work by tackling the issue of the corporate centre, both in terms of scale and impact. An attempt had been made previously to cut corporate centre costs through the adoptions of the percentage methodology – this had been effective but characterised by the Groups chairman as an “exercise in arithmetic”. The second attempt was more targeted and aligned with a strategic change of direction that took the company from being an old fashioned conglomerate to a new world portfolio business with a more PE style corporate centre. The blunt effect in terms of money and people was that about 50 percent of the Group’s Corporate Centre team departed, saving around £9m.

But on a more fundamental level a complete function review was undertaken, framed by a new set of Guiding Principles for the role of the Centre compared with the role of the Divisions. These Guiding Principles were crucial on a number of levels. At one end of the spectrum they clearly defined the roles and responsibilities of the Group Executive team and allowed the CEO to see how close individuals were to his vision of the work they would do and how that work would be done. At the other they were the starting point of a detailed piece of work looking at the role of corporate functions at each level in the organisation. This work created the in-depth frameworks which allowed the centre to hand over much greater responsibility and control for the day to day running of their businesses to the Divisional MDs.

Indeed, to their surprise, in the main they got what they had asked for in terms of management of a complete P&L together with elements of their balance sheet. In doing so the CEO also gained because for the first time in this company, custom and practice – which had been labelled as freedom but which were in effect, a day to day fiefdom culture – was replaced by agreed, bespoke and clear controls. Divisions were freed up and were also, of course, made more accountable, so that the CEO was in fact better informed and more able to spend time acting as the coach and performance manager of his businesses. The Divisional MDs naturally felt the need to continue the tradition and set about a root and branch reform of their organisations, raising another saving of £42m.

In the second example, reform started at the Divisional level with the establishment of clear Divisional remits where none had previously existed at the same time as giving the Divisional MDs a stiff savings target. The thinking was that, in themselves, either one part of the programme would have been insufficient to make the impact required. SG&A levels needed to be reduced, but more than that the business, which had grown by acquisition, had enthusiastically adopted the “castle and moat” theory of organisational design that allows individual Business Unit MDs hegemony in order to be able to manage profitability at a micro level.

The problem with this model is that once some level of operational scale has been achieved, the teams in the castles cannot see opportunities beyond their own lands and tend to tool up for scale work won locally when a bigger opportunity exists in the neighbouring land – the CEO gets a series of figures based on the maximisation of the current, and nobody asks the clients what they want. In creating visibility the change programme was also creating a broader set of accountabilities and giving the CEO the chance to play an effective role in supporting customer development rather than just being the highest point for complaints.

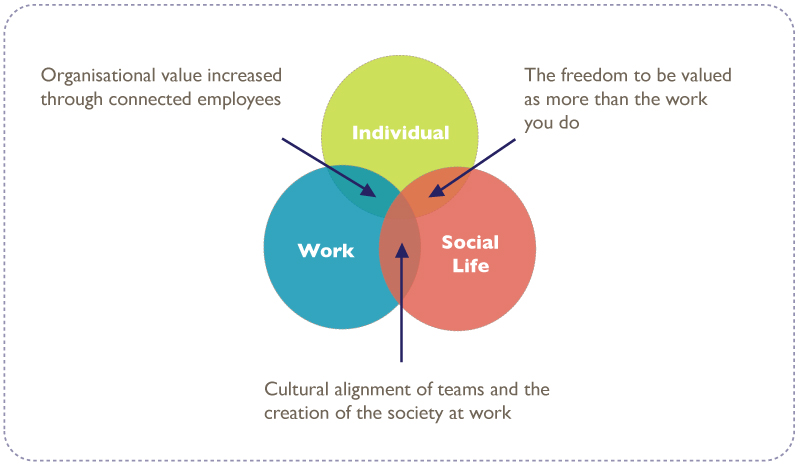

The value an organisation places on its people pays dividends when it comes to increasing organisation value.

Attempts at creating employee value propositions are often focussed on reward and recognition, specific HR policies such as flexible working, and prospects for individual career progression. These mechanisms may work on an individual level to get employees through the door, but are not necessarily linked to what’s most important for the organisation – the value created by its people.

When it comes to people, leaders reap what they sow, and too often the result is a workforce doing their jobs without understanding or committing to the wider cause. In society the question is ‘what does it mean to be British?’ For organisations it is just as important to build an understanding of ‘what it means to be a part of XYZ company’. Cost reduction and organisation alignment will not go all the way to building an effective organisation if the company culture is not setup to foster value-add behaviour.

In practical terms this means that leaders must be clear about what success looks like for the business and how teams and individuals contribute to this. Being able to link individual contribution to business value gives employees a clear sense of purpose – a key building block to encourage employees to go the extra mile. However this is just one side of the coin. Best intentions are quickly eroded without the right mechanisms in place to drive employee contribution with regular and consistent reinforcement of the desired beyond-the-call-of-duty behaviours. Performance reporting must be focussed on the things that matter to the organisation (e.g. innovation or business development), not just a way for business units to broadcast their achievements. Likewise individual performance management must be set up to capture and reward employee contribution that is beyond their job description and in line with the organisation’s proposition.

The challenge for CEOs therefore is to know at what point it is worth considering creating a more valuable organisation through a change to the organisation, rather than by continuing to press for performance out of the one you already have. Of all the factors to be considered the key ones internally are about the relationship between information and accountability.

In trying to create the right balance between the products, the people and the processes, CEO’s need to ask themselves whether the processes are there to support the people in what they want to do, or to develop and sustain the products and services on behalf of the customers. The main truth behind all of this is that when it comes down to it most of us would prefer to embark on a simple cost savings exercise or a process review without tackling the issues of accountability and agreement amongst the executive team – after all, a process doesn’t answer back.

The real enemy of organisational effectiveness is in this circumstance not lack of knowledge – though that doesn’t help – but a fear of getting the team into the room, hearing what they think, and having to forge an agreement with them. It’s hard work and involves facing up to both their view of you as a leader and their own talents and limits. Sometimes people don’t make it – both executives and CEOs – simply because they can’t stay focused and be decisive. In other circumstances of leadership – an unruly classroom, a battlefield, an operating theatre – there isn’t time for mulling things over. In too many businesses mulling leads to another strategy paper justifying the mulling until eventually only the shareholders can see the wood for the trees.

So CEOs look your people in the eye and ask, “Are we together and do I have the courage to lead you?” That’s effective.

Maxxim consulting works with CEOs and their leadership teams to connect their organisation with their strategy. This means at one end of the spectrum that structures and governance have to focus on the pillars of the strategy and support work in the markets they sell to. On a team or individual basis it means being clear about what needs to be done, who is going to do it and how best to achieve and behave. It is strategy made real and practical at all levels with a clear and undiluted link to value.

About the Author

Claire Arnold is a founding partner of Maxxim Consulting. She specialises in organisational strategy, change management and leadership development with significant experience in supporting leadership teams pre and post merger. Having been involved in a number of significant transformation projects in both public and private sectors, Claire has worked intensely with CEOs and their boards to develop and communicate business vision and strategy.

For further information, please visit: www.maxximconsulting.com