By Paul F. Nunes and Larry Downes

Industry-disrupting products used to enter the market as inferior but more affordable versions of existing offerings, giving incumbents time to respond. Today’s disruptors are not just cheaper – they’re better. And not better over time but right from the start. To fight back, companies must first understand the four economic trends that are making these new disruptors possible.

New products and services increasingly enter the market from “out of nowhere,” or so many long-established businesses think. Startups now regularly blindside incumbents with offerings that are immediately successful because they are both better and cheaper right from the start.

This deadly combination is the distinguishing feature of Big Bang Disruption, as we described in our book of the same name (Penguin Portfolio, 2014). The outcome is rapid and often near-total devastation, not only for once-successful companies but for entire industries. Many industries long-protected from digital disruption, including manufacturing, transportation, and education, are now under attack.

Startups may seem to have a decided edge in this game, but established companies can play too – and win. To succeed, they must adopt a dramatically different approach to strategy and execution, one that few senior executives, in our experience, are well prepared to embrace.

As a first step, business leaders must understand the economic trends that are enabling the phenomenon of “better and cheaper.” Powerful as they already are, these trends are likely both to accelerate in pace and to expand in influence for at least the next decade.

Four Economic Trends Powering Big Bang Disruption

Our cross-industry research on this new form of disruption reveals several technologically enabled economic trends that are pushing the pace of change. These developments are powerful on their own, but even more so in the way they interact.

1. Price Deflation

Prices have been falling for many products for decades. Some of the decline stems from broad improvements in business operations, driven by the improvement and declining cost of technology. Moore’s Law – which predicts that computing and related costs will drop by 50% every 12 to 18 months – is at the root of lower costs for many products. But something radically new is now afoot.

Today, the costs of production and innovation are falling at the same time.

In everything from health-tracking devices to 3D printers and drones, the impact of Moore’s Law has only just begun to wreak its disruptive potential. Sensors, gyroscopes, accelerometers, radios, magnetometers, commodity processors and other micro-electro-mechanical systems (MEMS) can now be sourced globally at steeply falling prices, driven largely by the cooling of demand for the smartphones and tablets they were originally created for. Thanks to new levels of supply chain visibility and modularity, these components can be easily designed into new disruptors in industries that have, until now, been largely immune to the information revolution.

Deflation in the price of core technology components goes far beyond Moore’s Law, though. Thanks in part to improvements in information technologies generally, exponential improvements in price and performance are also now being seen in other commodity technologies, including lighting, materials, energy storage, nanotechnology, biotechnology, imaging and genetic sequencing.

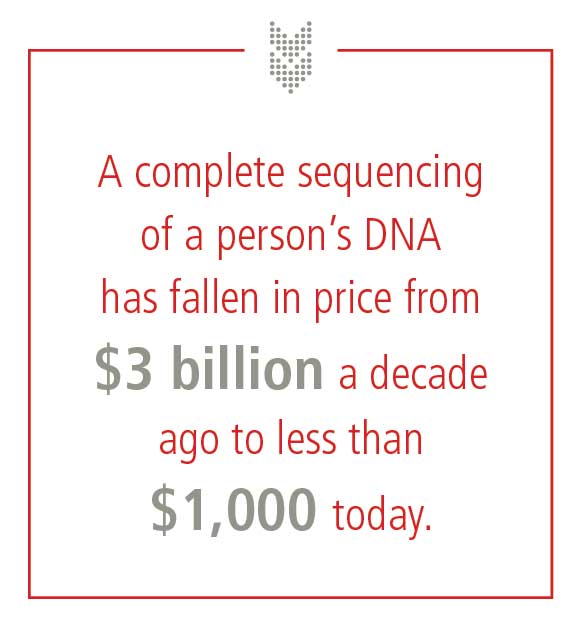

Graphene, a one-atom thick sheet of carbon that has exhibited profound conductivity and strength, is now being made in quantities large enough to begin serious experimentation. A complete sequencing of a person’s DNA has fallen in price from $3 billion a decade ago to less than $1,000 today. In displays, HD LED is being replaced by 4K OLED displays, which improve the number of pixels by another factor of four and makes possible curved displays. All the while, the price of displays predictably declines.

Graphene, a one-atom thick sheet of carbon that has exhibited profound conductivity and strength, is now being made in quantities large enough to begin serious experimentation. A complete sequencing of a person’s DNA has fallen in price from $3 billion a decade ago to less than $1,000 today. In displays, HD LED is being replaced by 4K OLED displays, which improve the number of pixels by another factor of four and makes possible curved displays. All the while, the price of displays predictably declines.

What do falling production and innovation costs mean for industries? Consider the automotive industry, where despite countless innovations the average real dollar selling price of a car has been declining for decades.

2. Platform Exploitation

A second important trend is the rise of technology platforms. Platforms allow businesses to develop, make and distribute new products and services at a fraction of the cost of traditional R&D and delivery.

Better-and-cheaper Big Bang Disruptors are being launched on robust hardware and software platforms featuring cloud-based computing and storage, mobile broadband networks and app-based tools. Apps that piggyback on existing cell phones, security camera networks, and the emerging Internet of Things, for example, can be sold at the cost of just the additional investment required to develop a new combination of existing components.

The value of using a platform built and paid for by others is obvious. Releasing new products on digital platforms not only lowers the cost of manufacturing and distribution, it also gives disruptors immediate access to millions (and soon billions) of users and devices. It also aids inactivating the social networks that can drive rapid product adoption for new offerings that consumers find compelling.

Many smartphone-based apps, for example, have rapidly made obsolete all manner of standalone electronics and analog products. The smartphone has become your boarding pass and train ticket, and will soon become your smart key at home and away. It may also replace much of what is still in your wallet, including cash and credit cards.

The fallout from this change can land on many an unintended victim. Consider the impact on alkaline battery manufacturers. Though still a multi-billion dollar business, battery sales fell four percent in 2014 alone, making batteries the worst performer among the top twenty-five categories of household products. Procter & Gamble, which owns Duracell, plans to spin off the division next year; Energizer Holdings is moving its vulnerable household-products into a separate business.

And it’s not just in consumer electronics that the impact is being felt. In agriculture, another kind of digital platform is emerging, as better and cheaper drone aircraft (whose parts largely come from mobile phone component producers) are giving rise to what is known as precision agriculture. This new platform is being built on autonomous tractors, GPS-based harvesters, wireless networks and sensors that report in real-time on soil condition, hydration, nutrients, weather conditions and pests.

In the energy market, the emerging platform is known as the “smart grid.” In Denmark, the government is pushing a smart grid strategy that will include deployment of smart meters, real-time monitoring of energy use and variable rates driven by high-volume data analysis. Eventually, the smart grid platform will balance demand and automatically create price incentives to encourage efficient energy use. And it will curb waste by identifying failing and inefficient devices.

3. Cross-Subsidisation

Goods and services can be sold cheap –and sometimes even given away for free – when their cost is being paid for, in part or in full, out of the revenues of a different business. Google can provide many of its services at no charge, for example, because the company can sell advertising and related marketing services through its core offering, online search.

The company’s search-based advertising revenues have in turn funded not just better search technology, but hundreds of subsidiary products including video hosting (YouTube), maps, photo management (Picasa), mobile device operating systems (Android), travel, office productivity tools, cloud storage, and much more.

In most of these examples, Google had no particular interest in disrupting or even competing with the travel agents, navigation device makers, and paid video and music providers that once sold those services. Google’s attention was instead focused on assembling world’s greatest collection of reusable information assets. Google’s strategy is being duplicated by many information-intensive disruptors, including most social networking companies such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Some companies are also succeeding with another form of cross-subsidisation: selling insights derived from large databases. Google draws on a massive number of customer interactions to improve its products, making, for example, its search and navigation databases and algorithms even better.

As the consumer experience improves, the user base continues to grow. Google can then refine its pricing model for advertisers, charging higher premiums for its larger base of customers and for its data-driven insights about those customers.

In effect, the cross-subsidised offering, like free Google Maps, becomes a kind of perpetual motion machine, driving further innovation and spreading the often unintended disruption of incumbents farther afield.

Still, it must be noted that subsidisation based big-data insights only works when the data comes from public sources of information, or from information that can be licensed for free or at very little cost.

Consider the problem faced by music services such as Pandora. Like Google, Pandora can increase its ad revenue and refine its music recommendation services by engaging more users, pushing the company to continue subsidising its core product. And as mobile broadband networks become better and cheaper, consumers are likely to increasingly prefer “renting” music from companies like Pandora, rather than owning it in the form of CDs or mp3s.

But at the heart of Pandora’s strategy is a ticking time bomb. The music it provides to consumers is licensed on a use-based model. Estimates are that for every million songs listened to by users, the company must pay licensing fees of about $1,500. That means the more consumers they sign up and the more each customer uses the service, the more fees Pandora pays.

Pandora makes nearly all of its revenue by advertising to listeners who sign up for the free service – so rising licensing fees for the music itself are causing the company to lose money. As things stand now, the more successful the company’s subsidisation strategy, the faster it goes into the red.

4. Marginal-Cost Elimination

Many goods and services cannot be exhausted through use or replication. This is true of most information goods. These might be thought of as the ultimate “sustainable” goods, in that heavier consumption does not require additional resources, nor does it exhaust supply. But it is not easy to make a profit on goods or services that cost nothing to make. Finding enough users willing to pay enough even to cover modest operating costs is challenging. And it puts incumbents holding debt for sunk costs in production assets at a distinct disadvantage.

Newspapers have been victims of this phenomenon, in some cases contributing to their own demise by offering digital versions of their content and allowing consumers to unbundle it, choosing the parts they like (the news) and ignoring the parts that paid the bills (the classifieds). While digital competitors with zero marginal costs experimented with alternate revenue models, the newspapers, with one foot still in the analog world, fell into a whirlpool of accelerating disruption.

The trend is now expanding to disrupt professional services, as the more mundane work of expensive human experts is being replaced by much cheaper digital alternatives. These new applications can perform increasingly sophisticated and repeatable tasks – reading X-rays, for example – at a marginal price at or close to zero.

In financial services, Intuit’s TurboTax software collects the same interview information as a human tax preparer, but then automatically generates the return. As the product’s users have grown into the millions, the company improves the product by observing the most frequent areas where customers rely on Intuit’s human backstop of tax advisors and then programs that knowledge into future releases. Software that learns can replace more functions currently assigned to human labour, erasing marginal cost as it moves up the evolutionary ladder toward true artificial intelligence.

A similar phenomenon is now beginning to transform the $200 billion market for legal services, stealing the low-end work done by lawyers and, at the same time, offering legal advice to many consumers who simply couldn’t afford the high-cost human alternative. Startups including LegalZoom, Shake, and Rocket Lawyer have already automated the easiest tasks, such as the creation of simple contracts and estate planning documents. Some of the services connect users to real lawyers for help preparing documents the software can’t do – yet.

* * *

• What is the trend for the real (inflation-adjusted) price of the goods and service you offer? What has it been in your industry?

• What physical production assets do your offerings rely on? Can they be replaced with digital alternatives? Or are they even necessary any longer in any form?

• At what point could your product or service become so cheap that others might simply give it away to support their own strategic aims?

• What do you sell that has little marginal cost, making it easy to sell again? Who else owns or invests in these information assets who might undercut your sales?

Today’s technology trends are conditioning buyers to look for greatly improved levels of value at prices even lower than they have paid in the past. Under these conditions, every company needs a strategy focused on offerings that are better and cheaper.

About the Authors

Paul F. Nunes is global managing director of the Accenture Institute for High Performance; he is based in Boston.

Larry Downes is Internet-industry analyst and a research fellow with the Institute; he is based in Berkeley, California.

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-100x70.jpg)