You cannot teach a man anything. You can only help him discover it within himself. — Galileo Galilee

The organizations we admire, and the places where most people would like to work, are known for having a special environment or corporate culture in which people feel, and perform, at their best. I have called these types of organizations, authentizotic. This term is derived from two Greek words: authenteekos and zoteekos. As a workplace label, authenticity implies that the organization has a compelling connective quality for its employees in its vision, mission, culture, and structure. The term zoteekos means “vital to life.” In the organizational context, it describes the way in which people are invigorated by their work. The zoteekos element of this type of organization allows for self-assertion in the workplace and produces a sense of effectiveness and competency, of autonomy, initiative, creativity, entrepreneurship, and industry.

These authentizotic organizations have meta-values that give organizational participants a sense of purpose and self-determination. In addition, people feel competent, experience a sense of belonging, have voice and impact on the organization, and they derive meaning and enjoyment from their work. Organizations with authentizotic cultures are not only benchmarks for health and psychological well being in the workplace, but they are very often profitable, sustainable enterprises as well.

What makes these types of organizations such great places to work is that its employees recognize the advantage of having well-functioning teams. Competitive advantage now lies with organizations that bring together their specialists in research, manufacturing, logistics, talent management, marketing, customer service, and sales with speed and efficiency to get their products and services to market. Organizations in social services, education, health care, and government also operate in complex environments that face similar issues and require a high degree of collaborative action. Across a wide range of organizations, teamwork can provide the competitive edge that translates opportunities into successes.

So why is it that, although authentizotic organizations seem so desirable when seen from the exterior, and so pleasant when experienced as an employee, ultimately so few organizations can claim to have this kind of organizational culture? Why is it that working relationships are so often dysfunctional? Why are so many executive teams ineffectual? Some answers may lie in our own human nature: our ability to trust one another just so far, and perhaps not far enough; and our inability to see past our own needs to understand that richer benefits, both psychological and material, may be easier to obtain through the collective efforts of a group rather than as individuals. But that is not so easy for us to accept, let alone change.

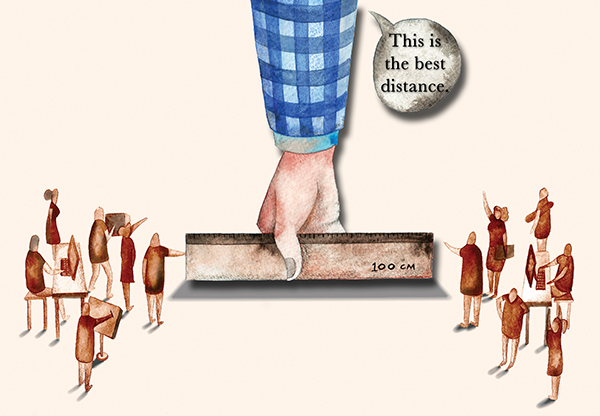

Arthur Schopenhauer, in a series of essays, called Parerga und Paralipomena, included a tale about the dilemmas faced by hedgehogs during winter. The animals tried to get close to one another when it grew cold, to share their body heat. However, once they did so, they hurt each other with their spines. So they moved away from each other to be more comfortable. The cold, however, drove them together again, and the same thing happened. At last, after a great deal of uncomfortable huddling and chilly dispersing, the hedgehogs discovered they were best off remaining at a little distance from one another.

Schopenhauer’s hedgehog’s dilemma was quoted by Sigmund Freud referring to the “sediment of feelings of aversion and hostility” in long-term relationships. In his essay, Freud asks a number of rhetorical questions about intimacy, the need for which is one of our most common, natural, human needs. How much intimacy can we really endure? And how much intimacy do we need to survive in this world? The hedgehogs’ quandary is also our own.

Almost every long-term emotional relationship between two people or more contains this “sediment” of negative feelings, which escapes perception because of the mechanism of repression. As the hedgehogs’ dilemma suggests, human relationships have a substantial degree of ambivalence, requiring us to contain contradictory feelings for the other person. Thus we can see Schopenhauer’s parable as a metaphor for the challenges of human intimacy. Are we destined to behave like these fabled hedgehogs—forever jostling for a balance between painful entanglement and loveless isolation? Will we always struggle with the fear of engulfment and the fear of loneliness?

Societal needs drive human hedgehogs together, but we are often mutually repelled by the many prickly and disagreeable qualities of others. We all have a simultaneous need for and fear of intimacy, creating a dilemma for commonsense living. The distance that Schopenhauer’s hedgehogs at last discovered to be the only tolerable condition of mutual interface represents our common code of conduct. A certain amount of distance is part of the human condition. Although our mutual need for warmth is only moderately satisfied by this arrangement, we are less likely to get hurt. We will not prick others—and others will not prick us.

We also see the hedgehogs’ dilemma within teams. To create authentizotic organizational cultures, how much closeness is too much? How much can we open up to others? What can we disclose about ourselves? What degree of intimacy is enough? And when is it necessary to set boundaries? Opening up too much can lead to an exposure of our weaknesses and make us vulnerable to shame and guilt reactions. This conundrum—our simultaneous need for closeness and distance—is a fundamental reason why people often find it so difficult to work successfully in groups and teams.

If we look closely at the organizational context, we can see how this dilemma plays out subtly, yet forcefully, in daily interactions. Teamwork is a crucial element of the effectiveness of organizations—in creating these authentizotic organizations—not the least because team alignment and goal orientation facilitates dealing with current crises and designing long-term strategies. The ability to work well in teams—to accept a certain degree of closeness—is undeniably essential in present-day organizations. Yet we too easily over-look the reality that for most teams, it can be very difficult to find the right balance between loose, inefficient connections at one extreme, and stifling interconnections at the other.

In addition, it is equally clear that many organizational leaders are ambivalent about teams. Too many of them have no idea how to put together well functioning teams. Their fear of delegating—losing control—reinforces the stereotype of the heroic leader who will do it all. For many, teams represent a hassle, a burden, or a necessary evil. This often becomes, not surprisingly, a self-fulfilling prophecy. Although many teams do generate remarkable synergy and excellent outcomes, some become mired in endlessly unproductive sessions, and are rife with conflict. As many of us have discovered to our despair, the price tag of dysfunctional teams can be staggering.

Paradoxically, the use of teams in the workplace is both a response to complexity and a further element of complexity. Ineffective teamwork can mean very high coordination costs and little gain in productivity. In some corporations and governments, the formation of teams, task forces, and committees is a defensive act that gives the illusion of real work while disguising unproductive attempts to preserve the status quo. At best, this does little harm because fundamentally it does nothing; at worst, team building becomes a ritualistic technique blocking important actions that might enhance constructive change. Dismantling a dysfunctional team might even require a kind of Gordian knot solution, which could lead to damaging outcomes both in economic and human terms.

More than meets the eye

Why do so many teams fail to live up to their promise? The answer lies in the obstinate belief that human beings are rational entities. Many team designers forget to take into account, however, the subtle, out-of-awareness behavior patterns that are part and parcel of the human condition. Although teams are created as a forum for achieving specific goals, the personality quirks and emotional lives of the various team members can cause deviations from the specified task. Indeed, there is often a degree of naivety among an organization’s leadership, who fail to realize that a group dynamic can derail a scheduled direction, so that the team’s real goals can deviate widely from its stated goals. Many people in positions of leadership fail to appreciate the real complexity of teamwork. They don’t pay heed to the hedgehogs’ dilemma.

Organizational designers need to accept that below the surface of human rationality lie many subtle psychological forces that can sabotage the way teams operate. But irrational as these behavioral patterns may be, there is a rationale to them, if we know how to disentangle the patterns. Meaningful teamwork entails numerous real risks for individuals, because of fear, anxiety, and uncertainty about the exercise of influence and power. If these concerns are not addressed, the anxiety generated by the risks involved in team working becomes too great and cannot be contained through leadership actions or facilitating structures: individuals will mobilize social defenses to protect themselves. These defenses, expressed through rituals, processes, or basic assumptions, displace, mitigate, or even neutralize anxiety but also prevent real work from being done. The result is preoccupation with dysfunctional processes and inhibiting structures that reinforce vicious circles preserving the status quo.

Executives need to realize that, when they create teams, there is more going on than meets the eye. Teams are forums in which sensitive organizational and interpersonal issues are dealt with discretely (and often indiscreetly). If people are to function non-defensively in the face of performance pressures in the workplace, they need leadership and supporting conditions that convert risk and anxiety into productive work. Unfortunately, team designers are largely unaware of concepts from psychodynamic psychology and systems theory, and the rational-structural point of view usually dominates.

I argue that a purely cognitive, rational-structural perspective on teamwork will be incomplete if it fails to acknowledge the unconscious dynamics that affect human behavior. In too many instances, organizations are treated as rational, rule-governed systems, perpetuating the illusion of the economic man as an optimizing machine of pleasures and pains, and ignoring the multifarious peculiarities that come with being human. Like it or not, there is no such thing as a Holy Grail of rational management. The rational-structural view of organizations has not delivered the promised goods. It has only created economic chaos and grief. Organizational designers need to pay attention to the conscious and unconscious dynamics that are inherent in organizational life. They need to become familiar with the language of psychodynamics—although I realize that this could be uncomfortable and disturbing for those who come from a traditional background in management or economics.

Creating and maintaining effective team-based work environments necessitates a dedicated focus on both the structural and the human aspects of organizational life. Innovative work arrangements can provide a structure and platform for team organizations, but these are not enough. The leaders of the organization must also instill, through their own example and through well-communicated codes of conduct, an internal, interactive coaching culture in which participants can engage in candid, respectful conversations, unrestricted by reporting relationships, or fear of retribution. It means establishing, and perhaps even enforcing, core values of trust, commitment, enthusiasm, and enjoyment. This can be a daunting challenge. It takes openness throughout an organization, and a willingness to change from a mindset of “me first” to “what’s best for the team?” But given the complexity of the new world of organizations, where those that master the multiplicity of lateral relationships will lead the pack, there is not much of a choice.

Creating the best places to work

The question is, how can organizations and their leaders initiate and perpetuate the kind of change in thinking and environment that supports an authentizotic culture based on thinking about the common good? One way of getting there may be through leadership group coaching. Coaching, which most commonly takes the form of one-on-one interactions between an executive and a coach, has changed the way many progressive organizations view professional and personal growth and development. One-on-one leadership coaching is an investment in future service potential, through building the talent pool in the organization, and helping people adapt to change.

One-on-one coaching certainly has its benefits, but personal experience has taught me that leadership group (or team) coaching—in essence, an experiential training ground for learning to function as a high performing team—is a great antidote to organizational silo formation and thinking, and a very effective way to help leaders become more adept at sensing the hidden psychodynamic undercurrents that influence team behavior. In leadership group coaching sessions, people who come from previously existing working groups, or in mixed-function groups, can experiment with the hedgehog dilemma—they can test degrees of closeness—metaphorically speaking, under the guidance of a trained facilitator. They can experiment with openness and trust in a safe setting, and see the advantages of better understanding the strengths and weaknesses of each individual. Knowledge transfer among group members becomes a natural activity, rather than something to be controlled. Essentially, people come to see the importance of effective group cohesion by experiencing it in the group coaching session.

Learning and unlearning

One of the prime functions when embarking on a change process using group coaching is to deepen the connections among executives and between executives and their organizations. The aim of the group coaching intervention technique is to liberate people from the hidden intrapsychic forces that prevent them from changing and from assuming a meaningful, authentic life in the organization.

Leadership group coaching not only helps team members acquire greater understanding of their own behavior (and how they are perceived by others) but also helps them to make sense of what happens in the team-as-a-whole, that is, the interpersonal and transpersonal processes that occur within a team. It encourages the members of the team to recognize, examine, and comprehend the prevailing group dynamics. It helps them to understand team members’ preoccupations in the here-and- now—mostly conscious but sometimes unconscious. At the level of hidden or meta-communication, it will enable them to decipher unconscious communications—that is, what is really going on between people, the “snakes under the carpet” that are generally avoided in ordinary discourse. Group coaching will encourage the participants to examine themselves, study their own dialogues, and their relationships to others, over- come their inner resistances to change, and apply and integrate their learning into concrete behavioral changes.

To create best places to work, it is important that the members of the teams that make up the organization are familiar with the mystery that is themselves. Only by studying human motivation from the inside (facilitated by a group coaching process), will they be able to truly understand what is happening on the outside. We all need to know our own strengths and weaknesses before we can be helpful to others. If this kind of understanding occurs, however, team members are more likely to create alignment between the goals of the individuals and those of the organization, creating greater commitment, accountability, and higher rates of constructive conflict resolution.

Furthermore, effective leadership group coaching interventions not only helps develop the coaching skills of each team member (through the process of peer coaching); it also accelerates an organization’s progress by providing a greater appreciation of organizational strengths and weaknesses, which will lead to better decision making. It fosters teamwork based on trust; in turn, the culture itself is nurtured as people become used to creating teams in which people feel comfortable and productive. When they work well, team-oriented coaching cultures are like networked webs in the organization, connecting people laterally in the same departments, across departments, between teams, and up and down the hierarchy.

To sum up, in creating the kinds of high performance teams that are part and parcel of authentizotic organizations, we need to pay heed not only to the structures and processes that facilitate team working but also to the more messy aspects of team dynamics. We need to go beyond what is happening on the surface, to become more aware of what lies beneath, including our ability to navigate our own unconscious world. As organizational participants, in order to get the best out of teams, we need to be comfortable with the worlds of fantasy and illusion that each of us carries within us. We should never forget that the world of humankind would not be what is without human fantasy as fantasy transforms reality.

*Adapted from “The Hedgehog Effect: The Secrets of Building High Performance Teams” by Manfred Kets de Vries, John Wiley & Sons (2011)

About the Author

Manfred Kets de Vries holds the Raoul de Vitry d’Avaucourt Chair of Leadership Development at INSEAD. He is also the Distinguished Visiting Professor of Leadership Development Research at the European Institute of Management and Technology in Berlin. He has held professorships at McGill University, the Ecole des Hautes Etudes Commerciales, Montreal, and the Harvard Business School. He is the author, co-author, or editor of 35 books and more than 350 articles, and has been the recipient of the International Leadership Association Lifetime Achievement Award for his contributions to leadership research and development. The Financial Times, Le Capital, Wirtschaftswoche, and The Economist have judged Manfred Kets de Vries one of the leading thinkers on management. (e-mail: [email protected])