By Mike Cooray, Rikke Duus, Joanne Carmichael, and Marius Sylvestersen

It has never been more urgent for entrepreneurial, public, and private organisations to join forces to deliver innovative solutions that can create sustained societal value. Based on our research into how organisations design, develop, and launch innovative collaborative initiatives with societal impact across Europe, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East, we introduce the STRIDE framework. STRIDE consists of six components: Strategise, Team Up, Review, Integrate, Deliver, and Evolve. We explain how organisations can use this framework to plan and guide their own UN SDG-led innovation in a processual and collaborative manner. Upon introducing the STRIDE framework, we share two real-world examples of UN SDG-led innovation that are expected to create positive impact for citizens, enhance well-being, and accelerate the transformation of urban living.

“The world is in turmoil.” This is a bold statement to start any conversation. However, during the last three years alone, we have clearly witnessed the vulnerability of the planet and the rapid change it has undergone, from the global pandemic to the devastating impact of climate change, to a war on European soil for the first time since the Second World War. The most recent COP27 in Egypt demonstrated how challenging it is to agree on initiatives and actions that can limit global warming to 1.5°C above preindustrial levels despite the extreme urgency. Ecosystem-based collaboration and transformational innovation are critical to solving the world’s many complex challenges.

Over several years, we have undertaken research with public sector institutions, large corporates, and entrepreneurial ventures that all engage in ecosystem-based innovation to drive positive social impact. Our research has broadly focused on understanding how these organisations organise, plan, and execute complex innovation initiatives. Common to them all is that societal equity and sustainability are at the core of their innovation approach. Yet, many organisations still prioritise innovating to outcompete others and driving profits, with less concern for their wider societal and environmental contribution. Whilst this may still be a viable approach for many businesses, we wish to suggest an alternative framework to explore innovation, leading with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) as the foundation.

UN Sustainable Development Goals

The UN’s 17 SDGs of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development came into force on 1 January 2016. The SDGs focus on 17 thematic issues, including water, energy, climate, oceans, urbanisation, science, and technology. Each SDG has a set of defined targets and indicators. For example, for SDG 4 Quality Education, target 4.1 is “By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes.” One of the indicators for this target is 4.1.2: “Completion rate (primary education, lower secondary education, upper secondary education)”. With these terms of reference, organisations can align their innovation and development of new solutions to specific targets and use the indicators as measures of impact. Still, collaborative innovation projects of this scale and complexity are often held back by regulations that have yet to catch up, lack of clarity in revenue models, and challenges in operational processes.

We posit that UN SDG-led innovation that has the aim of delivering sustained value to society and helping to solve complex societal challenges possesses a particular set of characteristics. Typically, this type of innovation requires an ecosystem approach, which means the participation and engagement of diverse organisations, including universities, innovation hubs, public and private sector organisations, and entrepreneurial ventures. Innovation outcomes and solutions that are aligned to UN SDGs will also need to coexist and be integrated within existing systems, processes, and legacy solutions in ways that can still unlock the new innovation’s intended impact and positive contribution. When driving UN SDG-led innovation, there is also an emphasis on using “tech-for-good” and thinking carefully about how technology solutions can sometimes have unintended negative consequences that need to be minimised.

Introducing STRIDE

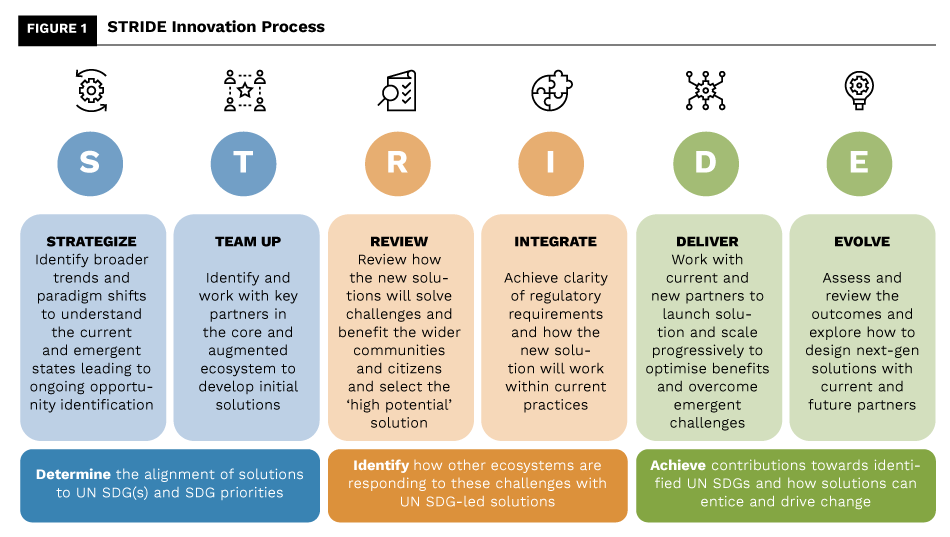

To assist private, public, and entrepreneurial organisations with their UN SDG-led innovation, we have developed a six-stage processual framework that we call “STRIDE” (see figure 1). STRIDE represents the six stages – Strategise, Team Up, Review, Integrate, Deliver, and Evolve – which make up this innovation process. The six stages are paired up according to an underpinning SDG focus. During the Strategise and Team Up stages, organisations seek to determine the alignment of solutions to UN SDGs and SDG priorities. During the Review and Integrate stages, organisations seek to identify how other ecosystems are responding to the identified challenges with UN SDG-led solutions. Finally, during the Deliver and Evolve stages, organisations seek to achieve contributions towards identified UN SDGs and understand how solutions can entice and accelerate change.

What makes STRIDE a useful process when planning for UN SDG-led innovation is that it takes an ecosystem-based approach to innovation, involving multiple partners and collaborators at the early stages of the innovation process. This kind of innovation will always require a collaborative approach and this is, partly, what makes it challenging. The STRIDE innovation process also encourages collaborators to consider the existing systems, practices, and solutions already in place to identify how the new solution can be effectively integrated into this environment. Often, this kind of complex and ecosystem-based innovation can fail if organisations have not sufficiently investigated the existing infrastructure and processes within which they hope the new solution can flourish

What makes STRIDE a useful process when planning for UN SDG-led innovation is that it takes an ecosystem-based approach to innovation, involving multiple partners and collaborators at the early stages of the innovation process. This kind of innovation will always require a collaborative approach and this is, partly, what makes it challenging. The STRIDE innovation process also encourages collaborators to consider the existing systems, practices, and solutions already in place to identify how the new solution can be effectively integrated into this environment. Often, this kind of complex and ecosystem-based innovation can fail if organisations have not sufficiently investigated the existing infrastructure and processes within which they hope the new solution can flourish

Strategise

The first stage of the STRIDE UN SDG-led innovation process is Strategise. We believe that to proactively engage in UN SDG-led innovation, organisations need to move away from a traditional strategic planning process, where a strategy is firmly set for several years and the organisation pledges to achieve these strategic goals. Instead, organisations will benefit from adopting a strategising approach; whilst there will typically be an overarching strategic vision, purpose and direction, the actions required to deliver on this are emergent, adaptable, and flexible. As part of strategising, organisations constantly scan the external environment to detect relevant changes in legislation, new technological developments, shifting industry priorities, new political shifts, emerging innovation clusters, and changes in citizen aspirations, to mention a few. Often, organisations will be interested in those changes that affect societies’ and citizens’ well-being and ability to prosper. Being alert to these multiple external shifts gives in-depth insight into the current state of play and will often end up redirecting the strategic vision towards unanticipated changes and related opportunities. By being alert to macroenvironmental shifts and flexible in their approach, organisations can laser-focus their efforts on specific SDG-led innovation discussions, projects, and initiatives that meet relevant needs and have a realistic chance of successful implementation. To better enable this, it is critical that teams be familiarised with the UN SDGs and, specifically, the relevant SDG targets and indicators.

By taking a strategising approach, it enables an internal alignment of the development of skills, competences and systems, and engagement with external networks that can help the organisation to adapt faster, be ready to respond to emerging needs, and participate in innovation ecosystems. To strategise in practice, organisations need to assemble teams of individuals who are accustomed to rapid change, driven to challenge the status quo, and comfortable with high levels of uncertainty. Organisations that can use a flatter structure with diverse and cross-functional teams who work on designated projects are often able to innovate at speed.

Team Up

Once organisations engage in strategising, new SDG-led innovation opportunities can become visible and the kinds of expertise, technologies, competences, and other resources that may be required to design viable and rapid solutions will also become clearer. Therefore, the second stage of the STRIDE UN SDG-led innovation process is Team Up. At this stage, the focus should be on identifying the core and augmented partners with whom to orchestrate an innovation ecosystem. This partner-based ecosystem should be built on transparency, honesty, and open agendas amongst partners and operate with a view to achieving mutual interests and generating positive societal impact. In our research, we have observed how complex and large-scale innovation projects can fail when there is friction amongst collaborators, priorities are misaligned, and there is a lack of transparency amongst ecosystem partners, which can significantly delay, derail, or even destroy the collaborative work.

The key actions at the Team Up stage are to identify relevant external partners who can come onboard to explore and investigate new possible solutions. The choice of partners will depend on what resources, skills, competences, and technologies are required to create solutions that deliver on identified UN SDGs, targets, and indicators. We recommend assembling an ecosystem of core and augmented partners who already engage with UN SDGs and therefore are actively seeking to develop solutions to societal challenges. When initially identifying potential partners, it is beneficial to invite a wide range of partners, which will help to generate interdisciplinary and cross-sector insight and understanding2. This is critical to designing solutions to complex societal challenges. Having multiple voices, perspectives, and experiences present can accelerate the process of moving from an initial idea to a scalable concept that creates mutual value for all partners involved as well as identified end users. In addition to delivery-oriented partners, we also recommend including expert individuals, research labs, or academic institutions that can contribute with in-depth understanding related to legislation, technology, data usage, and other issues that need to be considered.

It is critical to centre ecosystem partners around a joint vision and societal challenge informed by UN SDG priorities and targets. Therefore, the orchestrating ecosystem organisation needs to be able to allow diversity of thought, while also gaining some level of alignment amongst members, for new solutions to be generated at this stage.

Review

With the new potential solutions that have emerged from the coming together of the ecosystem partners, the focus is then on reviewing and evaluating which solutions to take forward. We recommend prioritising solutions that contribute positively towards SDG goals and targets and posses the following characteristics: use “tech-for-good”, can be implemented within a reasonable timescale, will clearly benefit wider communities and citizens, and will sustain partners’ interest in continued collaboration. Depending on the specific context, ecosystem partners should develop further criteria to use as part of the review process and may also undertake further research with potential end-users and other decision-makers to ascertain how the proposed solutions may respond to their needs and requirements.

The partner ecosystem may also wish to include pre-launch audits, simulations, operational testing, and/or consumer/citizen trials as part of the review process in addition to evaluating financial viability, partner contribution, and estimated cost of launch and operations. Understanding these aspects will be critical to deciding which solution possesses the greatest potential and can therefore be taken forward.

Integrate

A significant challenge facing SDG-led innovation initiatives is to integrate the new solutions into existing practices, systems, and processes. Adoption of a new solution can become stifled, not because the solution is unable to provide the intended benefits, but due to inherent restrictions that exist within the environment that the solution is brought into. These restrictions can come from existing processes, policies and regulations, and access to technology, as well as a lack of human competencies that prevent the solution from being fully integrated and utilised. Integrating new solutions into existing settings is often a challenge in highly regulated environments such as healthcare, education, and urban development, where many restrictions exist.

For partner ecosystems that seek to launch new solutions in these areas, it is important that all partners obtain a clear understanding of the current processes and systems in place. In many instances, the adoption of the new solution will depend on the time it takes to build new competencies amongst those who are intended to use the solution and the structural changes that will be required to ensure the delivery of benefits.

Deliver

Once the innovation partners have gained clarity concerning how the new solution can be integrated into current systems and processes, working with current and new partners to launch the solution at scale will be the next step in the STRIDE SDG-led innovation process. If a smaller-scale trial has already been actioned, the ecosystem partners can learn from this initial test and seek to overcome challenges encountered at this stage. From our research, we have seen that it is not unusual for organisations to struggle to successfully scale up from a pilot study to a full-scale solution implementation. The initial trial will generate useful feedback and insight, which may help to mitigate some unforeseen realities and expedite the delivery of the scaled solution. However, new challenges that did not become visible during the trial are likely to emerge when the solution is scaled up.

Partners should also seek to ensure that the supply chain and distribution infrastructure is in place to meet emergent demand, as any such delays can significantly damage the planned adoption of the new solution and the trust in the delivery ecosystem.

Evolve

It is critical that organisations and wider ecosystem partners evolve their interaction and do not bring the process of SDG-led innovation to a halt even when current solutions successfully deliver value to end-users and other stakeholders. Continuous evolution requires an open and transparent structure of collaboration, allowing new entrepreneurial ventures, innovation hubs, funding bodies, and other potential partners to get involved to participate in responding to societal challenges with new solutions. In sectors such as education, healthcare, and transportation, there are continuous opportunities to design and deliver transformative solutions, and ecosystem partners should build on successful projects, while also challenging the status quo. This will create an ecosystem that propels forward, made up of individuals and interdisciplinary organisations that are alert to the macroenvironmental changes and new possibilities created by the advancement of technology. The SDG targets and indicators can continue to create a unifying theme for collaborators and assist in focusing efforts and deliverables.

Case Example: NATO Centre for Quantum Technologies at Copenhagen University, Denmark

The following case example highlights the importance of working in collaborative ecosystems, driven by grand visions to transform society through the application of emerging technology. It is a “man on the moon” kind of project with a long lead time, yet seeking to harvest groundbreaking solutions from the get-go.

In 2022, Copenhagen University’s famous Niels Bohr Institute was selected to host a new NATO Centre for Quantum Technologies. Receiving the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1922, Niels Bohr was a groundbreaking Danish physicist who created the atomic model. This laid the foundation for how we understand atomic structure and quantum mechanics, which have had a profound impact on technological development. The Niels Bohr Institute was established in 1921 to support his pioneering work.

The grand vision is to build on the core technology, knowledge, and expertise that research scientists at Copenhagen University and the Danish Technical University already possess and then strategise to find new opportunities to apply quantum technology in areas beyond computing to drive large-scale innovation that can help solve complex societal challenges. In fact, the hope is that the work coming out of the Centre will become as memorable to the world as the original work of Niels Bohr.

To facilitate the development of new quantum technology-led solutions, the Centre is built on collaborative partnerships and actively builds ecosystems across sector domains and organisational types. Multiple large organisations across private and public sectors, including the Danish Meteorological Institute (public-private partnership), Novo Nordisk (knowledge partner), and the Danish Technical University (university partner), alongside researchers at Copenhagen University, have already come together to explore how to apply quantum technology in the healthcare sector. By teaming up, the objective is to develop new medicine and drive new-to-the-world research into epidemiology, genomes, and neuroscience, amongst other areas that support citizens’ quality of life and well-being (SDG 3). This research is supported with a grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation of DKK1.5 billion and the programme will run for 12 years. The first seven years of the programme will be spent building quantum computing platforms.

Alongside large organisations, the Centre for Quantum Technologies is also building on the energy of start-ups, tech innovators, and researchers who will collaborate through built-in test centres and accelerators to review and commercialise new solutions and drive spin-out companies. The combination of a test centre, designed to test and develop ideas, and an accelerator with the purpose of maturing solutions is a unique feature of this initiative. This is to ensure that the knowledge that is generated within the Centre “gets out of the lab” and into commercial solutions that can deliver benefits to society. This approach is critical to take from the start so that there is an understanding of how to integrate these into existing systems and processes or completely overhaul traditional solutions.

It is the expectation that the Centre will continue to evolve and grow as new collaborative partners join the initiative across societal domains and share knowledge towards delivering groundbreaking solutions that can transform our societies.

Case Example: Davao City High-Priority Bus System, the Philippines

Davao City is experiencing rapid urbanisation and has become the third-largest city by population in the Philippines, with about 1.8 million residents. Invariably, one of the major challenges for this growth is to meet the public transportation demands of citizens and communities. The current public transport needs are mostly met by “jeepneys”, which are public minibus-type vehicles, modified to meet local requirements.

Finding a solution to the transport infrastructure challenge requires strategising, not only to solve the problem, but also to ensure that the proposed new solution delivers human equity and positive environmental impact within the local context. Arup has taken on a lead role in supporting the Davao City Government in developing an SDG-led infrastructure design for implementation of a sustainable high-priority bus system (HPBS). Multiple partners have teamed up to design, plan, and launch this transport initiative, including Arup, the Asian Development Bank (ADB), Davao City Government, and the Department of Transport.

Finding a solution to the transport infrastructure challenge requires strategising, not only to solve the problem, but also to ensure that the proposed new solution delivers human equity and positive environmental impact within the local context. Arup has taken on a lead role in supporting the Davao City Government in developing an SDG-led infrastructure design for implementation of a sustainable high-priority bus system (HPBS). Multiple partners have teamed up to design, plan, and launch this transport initiative, including Arup, the Asian Development Bank (ADB), Davao City Government, and the Department of Transport.

The HPBS introduces a modern bus system with more than 1,000 buses on 29 new routes covering the city centre and surrounding areas. Reviewing how to further enhance the environmental impact of the new solution, Arup and ADB suggested including over 380 battery-powered electric buses to reduce climate- and air-pollution emissions. The HPBS also integrates five depots, three terminals, over 1,000 bus stops, and transit-priority elements including bus lanes and signal priority.

The project is a fast-paced, high-priority initiative that was developed during COVID-19. Delivering this project requires tapping into innovations in transport planning, including the use of geographic information systems (GIS) utilised for designing 600 km of bus routes and accessible bus stops to local communities.

Arup also devised a comprehensive electric-bus planning tool to simulate e-bus operations and to estimate fleet requirements and manage power demand.

This project is driven by future sustainability and connecting local communities, helping Davao City to establish an electric bus network with over 1,000 bus stops that improves daily commutes, passenger safety, and the environment. The project is aligned with national infrastructure development and international climate commitments, including the UN SDGs. Davao HPBS is undergoing tender, with full operations targeted for August 2024.

It is expected that the Davao City HPBS will accelerate and evolve the wider transport and community integration, taking a sustainable approach to providing solutions for future challenges.

About the Authors

Dr. Mike Cooray is a Professor of Strategy & Transformation at Ashridge Executive Education at Hult International Business School. Mike is an Academic Director on the MBA and Executive Masters Programmes and designs and delivers multiple digital transformation programmes. Prior to joining academia, Mike was employed with Carlsberg, Mercedes-Benz and Siemens, working across South East Asia, Europe and the UK. Mike’s research interests are in the areas of digital transformation, strategy and urban innovation. Dr Cooray frequently publishes his thought leadership and research in leading practitioner and global media outlets.

Dr. Mike Cooray is a Professor of Strategy & Transformation at Ashridge Executive Education at Hult International Business School. Mike is an Academic Director on the MBA and Executive Masters Programmes and designs and delivers multiple digital transformation programmes. Prior to joining academia, Mike was employed with Carlsberg, Mercedes-Benz and Siemens, working across South East Asia, Europe and the UK. Mike’s research interests are in the areas of digital transformation, strategy and urban innovation. Dr Cooray frequently publishes his thought leadership and research in leading practitioner and global media outlets.

Dr. Rikke Duus is Associate Professor at University College London School of Management and visiting faculty at ETH Zurich. She has a deep interest in how technology affects and influences the human experience and frequently presents her work at international conferences and events. Rikke is widely published in leading practitioner and global media outlets. She is interested in how digital technologies facilitate the emergence of inter- and intra-industry collaborative networks, how complex digital ecosystems require new types of mindsets, and the “darker” sides of data accumulation and surveillance.

Dr. Rikke Duus is Associate Professor at University College London School of Management and visiting faculty at ETH Zurich. She has a deep interest in how technology affects and influences the human experience and frequently presents her work at international conferences and events. Rikke is widely published in leading practitioner and global media outlets. She is interested in how digital technologies facilitate the emergence of inter- and intra-industry collaborative networks, how complex digital ecosystems require new types of mindsets, and the “darker” sides of data accumulation and surveillance.

Joanne Carmichael is a Chartered Engineer, a Fellow of the Institution of Highways and Transportation and Director for Arup in Cities, Planning and Design. She has held a board position with the Transport Planning Society in the UK and is currently the Global Skill Network Leader for Transport Planning for Arup. Over the last 25 years, she has worked in the UK, Middle East, Australia, and Southeast Asia on city-shaping, innovative projects, including the Master Planning of the Seychelles, Dubai Expo, the Surface Transport Masterplan for Abu Dhabi, and the Future Transport Strategy for Sydney.

Joanne Carmichael is a Chartered Engineer, a Fellow of the Institution of Highways and Transportation and Director for Arup in Cities, Planning and Design. She has held a board position with the Transport Planning Society in the UK and is currently the Global Skill Network Leader for Transport Planning for Arup. Over the last 25 years, she has worked in the UK, Middle East, Australia, and Southeast Asia on city-shaping, innovative projects, including the Master Planning of the Seychelles, Dubai Expo, the Surface Transport Masterplan for Abu Dhabi, and the Future Transport Strategy for Sydney.

Marius Sylvestersen is the Chief Innovation Officer at University of Copenhagen. He has been driving sustainable change at government and city level since Denmark hosted the UN Climate Change Conference in 2009. Marius is the former Director of Copenhagen Solutions Lab, where he was responsible for programme management, strategy development, and technology partnerships. Marius has a background in social science and is a thought leader on innovation, smart city, and the green economy.

Marius Sylvestersen is the Chief Innovation Officer at University of Copenhagen. He has been driving sustainable change at government and city level since Denmark hosted the UN Climate Change Conference in 2009. Marius is the former Director of Copenhagen Solutions Lab, where he was responsible for programme management, strategy development, and technology partnerships. Marius has a background in social science and is a thought leader on innovation, smart city, and the green economy.

References

- MacKay, B., Chia, R. and Nair, A.K. (2021). “Strategy-in-Practices: A process philosophical approach to understanding strategy emergence and organizational outcomes”, Human Relations, 74(9), 1337-69.

- Jacobides, M.G. (2022). “How to Compete When Industries Digitize and Collide: An Ecosystem Development Framework”, California Management Review, 64(3), 99-123.

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-100x70.jpg)