By Charleen R. Case and Jon K. Maner

Maximising your organisation’s effectiveness requires leaders who tailor their leadership approach based on the organisational culture, their team’s dynamics, and the specific task at hand. This article describes two distinct leadership approaches – dominance and prestige – each with their own advantages and drawbacks. To help your organisation reach its potential, select leaders who know how to leverage both.

Selecting people to help provide leadership is one of the most critical decisions an executive can make. When it comes to selecting an appropriate leader for a department, project, or any given team within your organisation, there are many factors you might consider. For instance, you probably will evaluate each candidate’s domains of expertise, level of experience, and the extent to which he or she is connected to key people and sources of information in your organisation and in the broader field or market. Indeed, these criteria are important to consider when evaluating whether a person has the knowledge, skill, and resources your team needs to achieve its goals. What these criteria fail to capture, however, is the extent to which a given candidate’s leadership approach is – or is not – congruent with the specific goals and nature of your team.

Recent research on leadership strategies1 and the motivations that underpin those strategies2,3 highlights the importance of looking beyond the knowledge, skill, and resources a potential leader possesses. Rather than focussing merely on what a person could offer your team as their leader, you also should consider why it is that that person wants to lead. What are the person’s underlying motivations for seeking the leadership role? In looking beyond candidates’ whats and focussing attention on their whys, you will be able to get a clearer sense of how they would behave as your team’s leader.

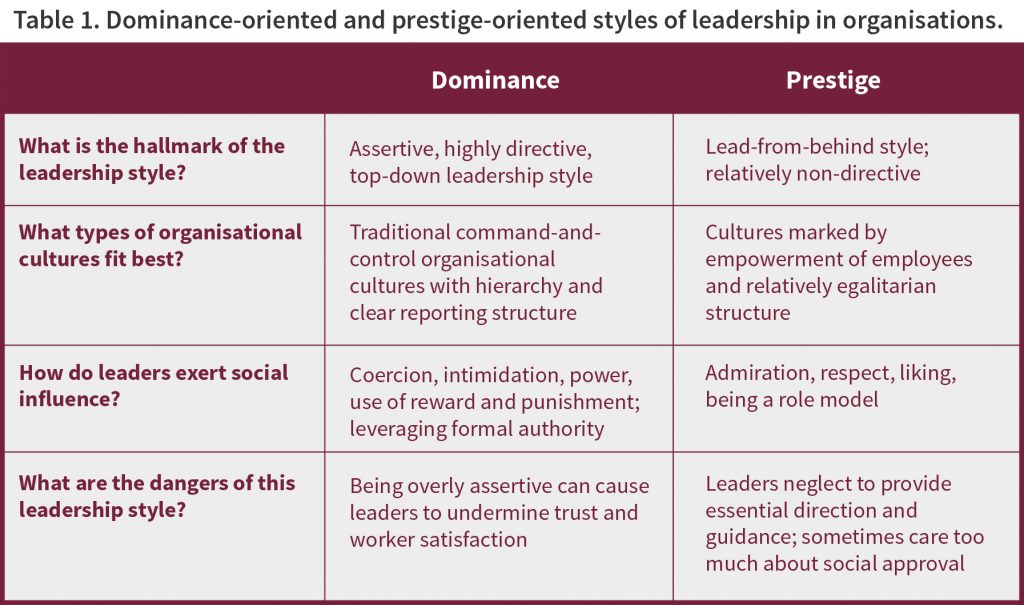

We and our colleagues have determined that, broadly speaking, there are two motivations that drive people to seek positions of leadership – dominance and prestige – and those motivations shape the strategies people use to lead others.4 On One hand, Dominance is characterised by a desire for the authority, control, and power that comes with formal positions of leadership. Prestige, on the other hand, is characterised by a desire for the admiration, respect, and elevated status often bestowed upon leaders. Although these two motivations are far from mutually exclusive – people can desire both formal authority and others’ admiration – the extent to which a person is more oriented toward dominance versus prestige has important implications for their leadership behaviour.

As leaders, dominance-oriented people enjoy making decisions for their team, giving orders, and getting things going. They are interpersonally assertive, sometimes overwhelmingly so. In meetings, they often do most of the talking and may even lower the pitch of their voice as a means to intimidate others.5 Dominance-oriented leaders often leverage their power and positions of formal authority to coerce people into doing what they want them to do. For instance, managers who are highly dominance-oriented tend to incentivise their employees with bonuses and promotions and coerce them with the threat of punishment. In essence, they are less concerned with fostering positive relationships with their team members than they are with getting things done – the way they see fit.

Prestige-oriented leaders behave quite differently. Because prestige-oriented people care deeply about their relationships with team members, they avoid using intimidation or coercion. Instead, they try to display signs of wisdom and expertise,6 so that they can be seen as a role model for their team. Unlike highly dominance-oriented leaders, leaders who are predominantly prestige-oriented are often able to influence their team because they are well-liked by their followers.7 Prestige-oriented leaders are not as assertive as dominance-oriented leaders, instead tending to lead from behind – providing guidance and direction but allowing their team the freedom to make some decisions on their own.

When it comes to selecting a leader whose approach is in line with your team’s goals, there is no “one size fits all” approach. Whether your team would benefit most from the kind of leadership strategies employed by someone who is predominantly dominance-oriented, predominantly prestige-oriented, or a mix of both largely depends on contextual factors. To determine which kind of leadership approach best suits your team, you should consider your team’s goals and the type of organisational culture you seek to cultivate.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]What Kind of Teams Benefit from Dominance-Oriented Leaders?

Dominance tends to function best when the organisation needs team members to get on board with a particular plan and to move forward with that plan via a highly coordinated and unified effort. Within such teams, it can be useful to have top-down leadership – someone who can call the shots and who expects his or her subordinates to fall into line. For example, in launching a new product in which the launch strategy is set and ready to go, a manufacturer may need the marketing team, sales teams, and product manager to work together to organise the launch. When each entity constitutes an essential piece of the puzzle, there is little room for independence. Each needs to do their part and that sometimes requires dominant leadership to provide clear direction.

Timing is another important factor. Imagine that the aforementioned manufacturer is facing a deadline for the product launch. When there is a tight deadline or insufficient time for out-of-the-box thinking, teams benefit from dominant leaders who are able to present a strong vision and make firm executive decisions. One benefit of dominance is that dominant leaders are in a position to provide structure and clear guidance to subordinates. Dominant leaders can cut through indecision to give subordinates concrete goals and benchmarks they need to meet. This approach can be effective when time is short, and you need everyone working quickly toward a desired outcome.

Dominance also works well in organisations that have a traditional command-and-control style culture. When people are used to following orders and adhering to a strict chain of command, dominant styles of leadership fit well with people’s expectations. Indeed, in contexts with a clear hierarchy, many subordinates prefer strong guidance and like to have mandates that help structure their operations.8 In such contexts, adopting a leadership approach that is too non-directive (i.e. prestige-oriented) can leave people feeling as though they lack the proper guidance and structure needed to do their job well.

When Prestige Works Best

Prestige, on the other hand, works well for teams that prioritise innovation, creativity, and out-of-the-box thinking. An advertising group that is looking to create a new ad campaign, for example, can benefit from leadership that lays out the goals of the campaign but places few constraints on the means to get there. This approach empowers team members to think creatively and pursue potentially novel solutions and sometimes surprising strategies that may promote success of the campaign. In such contexts, prestige-oriented leaders are not necessarily hands-off – they do provide essential input into the development process – but they avoid being overly directive or assertive. Rather than articulating a clear vision to the team, a prestige-oriented leader will provide the necessary means to facilitate the team’s vision. And at the end of the day, if needed, that leader can help distill team members’ individual contributions into a coherent strategy.

The prestige-oriented leadership approach works best when the team consists of people who possess the expertise and motivation to provide opinions, ideas, and self-direction. This leadership approach also is most effective when the team has the time necessary to arrive at a solution in a non-linear way. That is, because prestige-oriented leaders tend not to herd their subordinates into a decision, devising new strategies and solutions under this leadership approach can take time and multiple rounds of back-and-forth revision. Although decisions might take longer to finalise under this leadership approach, the end-result can often be highly innovative.

Prestige works best for organisations seeking to foster cultures of empowerment, in which workers are free to take chances and think outside the box. Prestige resonates with organisational cultures marked by relatively egalitarian relationships among coworkers, in which people at all levels of the organisation are accustomed to sharing their viewpoints having those viewpoints heard and respected.

Putting it All Together

Both dominance and prestige provide valuable approaches to organisational leadership. Different tasks and organisational cultures lend themselves to one leadership approach versus the other. The best leaders are able to leverage both approaches, tailoring their strategy to the specifics of the situation at hand. For example, in the initial stages of designing a new product, the organisation might want individual team-members to generate innovative ideas for exactly how the product might function. And at that stage, prestige-oriented leadership can empower individuals within the team to generate a creative end-solution. However, once the plan is set, and the job is to get a range of people within the organisation working in a coordinated fashion to deliver on that vision, a more top-down dominant leadership approach could work best.

While both dominance and prestige have their advantages, both also have potential drawbacks. For example, although dominant leadership can provide important top-down operational structure, overly dominant leaders can come across as narcissistic and self-involved, and are often disliked by subordinates and colleagues. This can undermine worker satisfaction and, thus, the leader’s effectiveness. To help avoid this problem, dominant leaders should try to remain sensitive to the feelings of others in the organisation – to take their perspective so that they can avoid behaving in a way that leaves others feeling demoralised or exploited.

At the same time, being overly prestige-oriented can lead executives to fall short of providing others with proper guidance and direction. Indeed, highly prestige-oriented leaders sometimes can care too much about what others think of them, and worry too much about being negatively evaluated. This can lead prestige-oriented leaders to prioritise what others think of them over the performance outcomes of the organisation. To avoid these problems, prestige-oriented leaders should make sure they provide clear goals and expectations to team members, so that they can provide essential feedback and course corrections when needed. They should also work hard to build trust over time with coworkers and subordinates, so that when they do need to make unpopular decisions or provide others within negative feedback, they can do so while keeping their relationships intact.

Maximising your organisation’s effectiveness means selecting leaders who can leverage the advantages – and avoid the potential dangers – of each leadership approach. Both dominance and prestige have their time and place, and both can be quite effective at motivating others. Ultimately, the most effective leaders are those who are able to diagnose the organisation, the team, and the specific task and, based on that information, implement the leadership approach that will work best.

[/ms-protect-content]About the Authors

Charleen R. Case (left)is an Assistant Professor of Management and Organizations at the Stephen M. Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan. Her work explores how fundamental motives shape organisational behaviour in the context of leadership, social hierarchy, and coalitions. Jon K. Maner (right)is Professor of Psychology at Florida State University. His work applies an integration of social psychology and evolutionary psychology to research on social relationships, leadership, and social hierarchy.

Charleen R. Case (left)is an Assistant Professor of Management and Organizations at the Stephen M. Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan. Her work explores how fundamental motives shape organisational behaviour in the context of leadership, social hierarchy, and coalitions. Jon K. Maner (right)is Professor of Psychology at Florida State University. His work applies an integration of social psychology and evolutionary psychology to research on social relationships, leadership, and social hierarchy.

References

1. Cheng, J. T., & Tracy, J. L. (2014). Toward a unified science of hierarchy: Dominance and prestige are two fundamental pathways to human social rank. In J. T. Cheng, J. L. Tracy, C. Anderson (Eds.). The Psychology of Social Status (pp. 3-27). Springer New York.

2. Case, C.R., & Maner, J.K. (2015). When and why power corrupts: An evolutionary perspective. In J. H. Turner, R. Machalek, and A. Maryanski (Eds.). Handbook on evolution and society: Toward an evolutionary social science(pp. 460-473). Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

3. Maner, J. K., & Case, C. R. (2016). Dominance and Prestige: Dual Strategies for Navigating Social Hierarchies. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 54, 129-180.

4. Ibid.

5. Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., Ho, S., & Henrich, J. (2016). Listen, follow me: Dynamic vocal signals of dominance predict emergent social rank in humans. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General,145(5), 536-547.

6. Henrich, J., & Gil-White, F. J. (2001). The evolution of prestige: Freely conferred deference as a mechanism for enhancing the benefits of cultural transmission. Evolution and Human Behavior, 22(3), 165-196.

7. Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., Foulsham, T., Kingstone, A., & Henrich, J. (2013). Two ways to the top: Evidence that dominance and prestige are distinct yet viable avenues to social rank and influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(1), 103-125.

8. Tiedens, L. Z., Unzueta, M. M., & Young, M. J. (2007). An unconscious desire for hierarchy? The motivated perception of dominance complementarity in task partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(3), 402-414.

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-100x70.jpg)