By Vadim Grigorian and Francine Espinoza Petersen

In luxury brand management, experiences are essential. However, most of what we know about designing customer experiences originates from work developed with and/or for mass brands. Luxury brands are conceptually different and require a specific approach to brand management. This article offers a framework to guide you through the design of building a luxury experience.

We are living the experience economy. Experiences engage customers and in creating memorable events connect them emotionally to the company or the brand.1 An increasing number of organizations are placing experiences at the core of their marketing strategy2 and, in luxury brand management, experiences are essential.3,4 However, most of what we know about how to design customer experiences originates from work developed with and/or for mass brands.5,6 Luxury brands are conceptually different and require a specific approach to brand management.7

Through our research we discovered that the holistic brand experience that high-end brands (e.g., premium and luxury brands) offer goes beyond the recommendations of traditional branding frameworks. The luxury experience is different from “simply” offering the highest possible level of quality in each of the brand touch-points with the consumer and, consequently, should be designed and managed differently. We developed a framework that can help managers design a luxury experience. Although high-end brands would benefit the most from applying the principles of the framework, virtually any brand can apply (at least some of) the principles to offer a differentiated customer experience and strengthen its brand.

Experience Design and Luxury Experience

Experiences occur when customers interact with one or more elements of the brand context and, as a result, extract sensations, emotions, or cognitions that will connect them to the brand in a personal, memorable way.8,9 Specific aspects of the brand context, such as store atmosphere or human elements,10 influence customer experience. However, customer experience is holistic.11 A company should orchestrate an integrated series of “clues” that will, collectively, determine how customers experience the brand.12,13

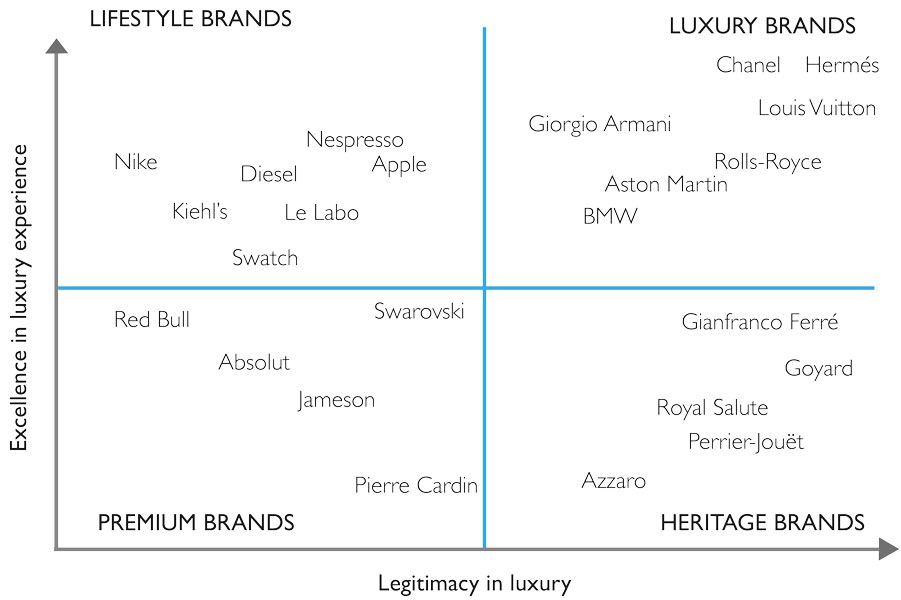

To design a luxury experience, it is important to first define what a luxury brand is. We agree with the perspective that luxury brands are conceptually distinct from brands with extreme levels of premiumness.14 We advocate that owning “legitimacy in luxury” is a necessary, though not sufficient, condition for a brand to be or become a luxury brand. Legitimacy in luxury includes an exceptional production process (often based on craftsmanship, uniqueness, and exclusivity), a product of the highest quality (often design-based, instigating consumers’ emotions and self-expressive motivations), and a tradition or history associated with the brand. Another condition for a brand to become a luxury brand is excellence in experience. Consider, for example, the brand Azzaro (apparel and perfume), which was at its peak in the 1970s–1980s. Today this brand has lost much of its luxury appeal despite owning legitimacy in luxury. Luxury experience provides the symbolic value and emotional connection that luxury brands need to keep the “dream component” of luxury brands alive.17

What is luxury experience? Conventional wisdom suggests that luxury experience is achieved by offering the highest quality in any of the elements that mass brands also offer. For example, the product offered should be of exceptional quality like the luxurious stairlifts. The service added to the offering should be delivered impeccably. We believe this is not enough to design luxury experience. This is because we believe that luxury experience goes beyond extreme premiumness.

The luxury industry is idiosyncratic. Luxury is more than the material offering (even if the offering is a service). Luxury is a differentiated offering that delivers symbolic and experiential value besides functionality.18 At times, ironically, offering symbolic and experiential value requires luxury brands to not offer “impeccable quality”19. For example, while many could think of a Ferrari’s noise and wasted potential as product “flaws”, from a luxury experience perspective these are part of the brand’s philosophy: In luxury, passion and dreaming are as important as functionality. We learned through our research (see the appendix on the web edition for our methods) that to achieve excellence in luxury experience, a similar approach applies: Brands must go beyond what traditional branding frameworks recommend to create luxury experience.

1. Beyond brand values, beliefs

Luxury brands should advocate beliefs to their customers. Beliefs can be seen as the brand’s philosophy, apparent both at product and brand levels, and which becomes a guiding principle for those brands. Beliefs go beyond brand values because beliefs are more specific (though subjective) and consequently more segmenting. Unlike mass brands, luxury brands should not strive to please everyone, but should attract those customers whose beliefs are similar to theirs. For example, Louis Vuitton, beyond the brand value of “travelling”, believes in practicality. Louis Vuitton initially embarked on innovation by substituting round suitcases with rectangular, flat-bottom models that could be stacked. While some consumers may dislike Louis Vuitton, those who identify themselves with the brand’s beliefs are likely to connect with the brand at deeper levels. Ferrari believes in performance and, as a consequence, it rarely advertises; however, it invests significant amounts in Formula 1 events. It focuses on actions related to its beliefs to reinforce those beliefs in consumers’ mind. Premium brands can apply this principle to create a customer experience that resembles a luxury experience. For example, La Martina applies this principle by defining itself not as a fashion brand, but as a polo brand (it sells apparel and accessories related to the polo lifestyle). La Martina reinforces this belief in several touch-points, such as the atmosphere of its stores, the design of its clothes, and by being constantly present at polo events.

2. Beyond a logo, a set of visual icons

When consumers think of a true luxury brand, they likely think of a whole set of visual icons that can include monograms, brand symbols, logos, colors, patterns, images, or even concepts. For example, leather goods from Bottega Veneta display no visible brand symbols, but many consumers recognize the weaved leather pattern for which the company is known. The stronger the brand, the broader the spectrum of icons can be. When one thinks of Chanel, for instance, the colors black and white, the intertwined c’s, the number five, a string of pearls, a camellia, and a little black dress might come to mind. Luxury brands should actively choose their symbols and iconize them through constant and consistent repetition. A good example is the black dress, which appears revisited in Chanel collections every year. Luxury brands can also repeat design elements across a product range: The face of the watch in Chanel’s Premiere Collection is the same shape as the stopper of the Chanel No. 5 perfume, which in turn takes its shape from the Place Vendome in Paris. Absolut Vodka is an example of a premium brand that has adopted the principle of luxury experience. In over two decades and more than 800 collaborations with artists, Absolut has iconized the shape of its bottle by consistently developing advertisements focusing on its interpretation.

Figure 1. The 7 Principles of Luxury Experience

3. Beyond a product, a unique ritual

True luxury brands cannot stop their offering at the product. Luxury brands should go beyond that and offer unique services or rituals. This can start with attentive salespeople and prompt customer service, but it should go beyond that to offer a differentiated, unique buying and consumption “ritual” that exceeds expectations. A powerful example of moving beyond products and offering a unique ritual is the perfume brand Le Labo. Using the premise that the quality of perfume deteriorates over time, it revolutionized the consumer buying experience by offering a personalized and special experience: each Le Labo perfume is hand-blended and individually prepared in front of the customer at the moment of purchase. The glass decanter is then dated and the customer’s name is printed on the label. After taking the package home, the customer needs to let the perfume marinate in the fridge for one week before wearing it. It becomes a personal, exclusive, and unique choice of fragrance.

4. Beyond a point of sale, a temple

Luxury brands must pay special attention to the way they sell and innovate at the point of purchase. Where before luxury brands used brick-and-mortar stores mainly to sell products, they now aim at designing multifunctional, controlled spaces to create brand experiences and communicate brand beliefs through events, exhibitions, and collaborations. These stores function almost like religious temples for discerning consumers. For example, Prada embarked on a unique project in combination with AMO, a research studio based in Rotterdam, and the renowned architect Rem Koolhaas. The result was a wide-ranging project that included special “Epicenters”: stores designed to provide a working laboratory for experimental shopping experiences. The project also included a plan for an extended web presence, the development of specialized, site-specific shopping tools, the application of emerging technology, and innovative programming ideas such as exhibitions, film screenings, concerts, and other public events. BMW World in Munich is another example of a temple-like showroom where consumers can experience the brand. The initiative entertains, engages, educates, and interacts with consumers in an environment that materializes the BMW brand. Brands like Apple and Nike have similarly transformed their stores into temples in their respective “Apple Store” and “Nike Town”. The temple is the opportunity that the brand has to physically connect with the customer. The “Red Bull Station” in São Paulo was designed to “give wings” to young artists by providing them with music studios, artist residencies, and exhibition spaces. Importantly, creating a temple does not necessarily require high investment. Kiehl’s uses its small stores to offer customers a consistent and attentive experience that is unique in the cosmetics industry. Used in this way, the store-turned-temple is a brand’s best opportunity to connect with consumers.

5. Beyond segmentation, access to a parish

Mass brands define groups or segments of consumers and push products towards them. For luxury brands the roles are reversed: consumers are pulled towards the brand with the promise of belonging to the exclusive community. Many consumers want access to this special group, but, similar to what happens with many religions, only a select number who share the brand’s beliefs may truly belong. In addition to using pricing or distribution to naturally segment customers, luxury brands create other artificial barriers or initiation rituals to select which consumers gain admittance. They may even deny access to customers with the means to purchase. For example, Hermés customers have to form a long-term, intimate relationship with the store before they are given the opportunity to buy one of the brand’s “it” bags. Rather than putting off customers, this behavior creates a sense of belonging to a special group. Customers who are admitted then stay for a long time and are rewarded for their loyalty. For example, Aston Martin extends invitations to events and maintains one-on-one relationships even with customers who bought their cars fifteen years ago.

6. Beyond communicating value, myth-telling

Mass brands aim to communicate their value or advantages over other brands, but luxury brands don’t push consumers to buy products. Rather, they communicate the legends associated with the brand. Myths should be conveyed indirectly and should be consistent in every point of delivery, including products, stores, or marketing actions. Myth-telling is a subtle narration of the story and heritage of the brand. Luxury brands often do this by inducing a certain degree of mystery, or by making a connection with art to tell the myths in an elevated way.20 For example, Rolls Royce invites a few selected customers to visit its manufacturing facilities to see and experience its storied production process in person. Yet, there are no direct messages, no pushing a customer to buy something.

7. Beyond a category, a way of life

The final element of the framework suggests that luxury brands should move beyond the mental limits of a product category and offer a “way of life”. At some point, strong luxury brands will sever their association with the product category in which they are rooted and push the brand to the ultimate level of intangibility. In other words, they sell a pure aesthetic principle and offer consumers a certain way of life. One way to offer a way of life is through horizontal brand extensions. For example, Giorgio Armani created a homogeneous and consistent world across a wide range of categories (e.g., clothing, accessories, cosmetics, home furnishings) for customers embracing the brand’s signature minimalist style. Ultimately, by extending its “Stay with Armani” philosophy to the Armani Hotel, where the brand’s style is woven into each of the guest rooms and suites, Armani makes it possible for customers to live both with and within the brand. Another way to offer a way of life is to collaborate with other brands. An interesting illustration is a collaboration between the Porsche Design Group and Poggenpohl, a luxury kitchen brand, to create a high-design kitchen for men.

Figure 2. Excellence in Luxury Experience and Legitimacy in Luxury Define True Luxury Brands

We believe that offering a way of life is the ultimate behavior of a true luxury brand, because it requires the brand to possess other strong attributes that can be communicated subtly. For example, Armani’s strategy would not make sense if Armani’s icons and beliefs were not strongly present in the mind of consumers. Offering a way of life must be based in authenticity and must be consistent with what the brand represents.

Implications

Although creating a strong luxury experience is crucial for high-end brands, virtually any brand can benefit from applying at least some luxury experience principles. While luxury brands can apply the principles to create, recreate, or reinforce a luxury world, any brand can achieve excellence in luxury experience to then become, or at least resemble, a luxury brand. Figure 2 depicts how excellence in luxury experience can help brands to enhance their position.

Brands that do not own legitimacy in luxury can apply the principles of the framework to become lifestyle brands, premium brands that offer an enhanced experience. Although these brands cannot become true luxury brands unless they acquire legitimacy in luxury, they can adopt luxury experience principles to increase their brands’ desirability. In other words, the framework offers a roadmap for brand managers to follow a “trading-up strategy”21

Brands that have enjoyed a true luxury status in the past and have lost ground may apply the principles of luxury experience to regain their status. For example, Royal Salute whisky is improving its positioning as a luxury brand by applying some of the luxury experience principles. Created in 1953 to celebrate the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, the brand is emphasizing its “royal beliefs”. By working closely with polo enthusiasts (e.g., providing support for global polo events, using polo player Facundo Pieres as a brand ambassador), Royal Salute affiliates itself with the “parish” that holds the same beliefs. It also has an ephemeral “temple” in the Tower of London, where it holds special events for customers to taste and savour the whisky and experience the brand while helping support the Tower of London.

Brands with legitimacy in luxury that fail to follow the principles of luxury experience do not achieve the status of true luxury brands. We call these “heritage brands” because they have what it takes to be a luxury brand but fail to offer an excellent luxury experience.

Finally, brands with legitimacy in luxury can achieve excellence in luxury experience and thereby reach the status of a true luxury brand. These brands can monitor their behavior to maintain or enhance their privileged positions. Louis Vuitton, for example, has moved towards greater popularization. Recently, however, the brand increased the price of its products to reduce their accessibility. In addition, it created a new handbag that was released in small batches, generating a long waiting list.22 These monitoring and protective measures help the company to maintain its position as a true luxury brand.

About the Authors

Vadim Grigorian is Marketing Director of Luxury and Creativity at Pernod Ricard. He consults key hi-end brands of the company on their luxury development, such as Martell, Royal Salute and Perrier-Jouët. He also implemented art world engagement strategy for Absolut. Previously he was Marketing Director of Russia and Eastern Europe at Pernod Ricard. Vadim holds an MBA from INSEAD and is author of several award winning business cases.

Francine E. Petersen is Associate Professor of Marketing at the European School of Management and Technology (ESMT). Her research focuses on consumer emotions and luxury consumption. She holds a PhD from the University of Maryland, was Visiting Professor at Columbia Business School, and has experience as a marketing manager and marketing research consultant. She teaches seminars related to branding, consumer behaviour, and luxury at MBA, Executive MBA and executive education levels.

Appendix 1. Research Method

The data collection process included visits to stores, sites, and plants across the world, and more than 50 key decision makers such as CEOs, executive board members, directors, designers, and brand or product managers working in the luxury industry. The geography of the interviews is diverse, with focus on the main cities in France, the United Kingdom, China, Korea, Japan, Hong Kong, United States, Russia, and Brazil. Markets included perfumery, jewelry, watches, drinks, fashion, services (hotels), leather goods, and cars. We have also drawn from our practical and academic experiences in the management of luxury brands and conducted an extensive literature review of managerial, research, and press articles and books.

Our research followed a grounded theory approach to develop the framework. Grounded theory is an inductive method used to generate theory through the systematic and simultaneous process of data collection and analysis.[i],[ii] Our analysis was based on continuous comparisons between data collected via interviews, field observations, and analysis of these data through practical and theoretical lenses.

The executives were recruited from our personal network or using a snowball technique (convenience sample). The initial interview guide was organized around the theme of “defining a luxury brand” and contained some fixed questions that every interviewee had to answer (e.g., “what are the pre-requisites for luxury in your opinion?” “what differentiates a luxury brand from a premium brand?”) as well as some questions that were adapted to a specific industry or a particular business. Following the grounded theory approach, and as the core categories were emerging, we adapted the questions to gather more specific data. The interviews were set in an informal atmosphere and lasted from one to three hours.

We visited stores, sites, and plants (e.g., Rolls Royce, Ferrari, Martell, Perrier-Jouët, among others) in Europe, America, and Asia to observe how luxury brands present themselves. These visits were accompanied by the senior management of the respective brands (e.g., Hermés in Tokyo was accompanied by the general manager of Hermés Japan). During the visits, we systematically observed the point of sale in detail, noting how the brand presents itself, the associations with the brand (e.g., art), how customers are treated, whether and how the story of the brand is told, the presence and consistency of visual icons, and whether additional physical brand experiences were offered. These observations aided the analysis of the interviews and provided examples described in this article.

The data analysis followed a three-step approach.[iii] In the first stage of data analysis (open coding), we obtained core categories – or themes – related to luxury experience. The relevant categories that emerged include aspects of customer experience previously recorded in the literature but they also included brand-related aspects that, to the best of our knowledge, have not been previously examined as part of the “context” influencing customer experience. In the second stage of data analysis (axial coding), we categorized examples and passages of the interviews according to the identified core categories. At this stage we were able to better understand each of the identified themes. In the third stage of data analysis (selective coding), we organized the conceptual relationships between the identified categories and named them. Our analysis is built upon comparisons between the data collected through these different means.[iv] As a result, we were able to draw a parallel between the elements of brand management that create customer experience in mass markets and the elements of brand management that create a luxury experience.

References

1. Pine, B. J. and Gilmore, J. H. (1998) “Welcome to the Experience Economy,” Harvard Business Review, 76/4 (July/August): 97-105.

2. Frow, P. and Payne, A. (2007) “Towards the ‘Perfect’ Customer Experience,” Journal of Brand Management, 15/2 (November): 89-101.

3. Atwal, G. and Williams, A. (2009) “Luxury Brand Marketing – The Experience is Everything!” Journal of Brand Management, 16/5 (February): 338-346.

4. Berthon, P. R., Pitt, L. F., Parent, M. and Berthon, J.P. (2009) “Aesthetics and Ephemerality: Observing and Preserving the Luxury Brand,” California Management Review, 52/4 (Fall): 45-66.

5. Verhoef, P. C., Lemon, K. M., Parasuraman, A., Roggeveen, A., Tsiros, M. and Schlesinger, L.A. (2009) “Customer Experience Creation: Determinants, Dynamics and Management Strategies,” Journal of Retailing, 85/1 (March): 31-41.

6. Pullman, M. E. and Gross, M. A. (2004) “Ability of Experience Design Elements to Elicit Emotions and Loyalty Behaviors,” Decisions Sciences, 35/3 (August): 551-578.

7. Kapferer, J.N. and Bastien, V. (2009) “The Specificity of Luxury Management: Turning Marketing Upside Down,” Journal of Brand Management, 16/5-6 (March-May) : 311–322.

8. Gupta, S. and Vajic, M. (2000) “The Contextual and Dialectical Nature of Experiences,” in New Service Development-Creating Memorable Experiences, ed. James A. Fitzsimmons and Mona J. Fitzsimmons, 33-51 (Thousand Oaks: Sage).

9. Pine, B. J. and Gilmore, J. H. (1998) “Welcome to the Experience Economy,” Harvard Business Review, 76/4 (July/August): 97-105.

10. Baker, J., Parasuraman, A., Grewal, D. and Voss, G. B. (2002) “The Influence of Multiple Store Environment Cues on Perceived Merchandise Value and Patronage Intentions,” Journal of Marketing, 66/2 (April): 120-141.

11. Verhoef, P. C., Lemon, K. M., Parasuraman, A., Roggeveen, A., Tsiros, M. and Schlesinger, L.A. (2009) “Customer Experience Creation: Determinants, Dynamics and Management Strategies,” Journal of Retailing, 85/1 (March): 31-41.

12. Berry, L. L., Carbone, P. L. and Haeckel, S. H. (2002) “Managing the Total Customer Experience,” MIT Sloan Management Review, 43/3 (Spring): 85-89.

13. Meyer, C. and Schwager, A. (2007) “Understanding Customer Experience,” Harvard Business Review, 85/2 (February): 118.

14. Kapferer, J. N. and Bastien, V. (2008) The Luxury Strategy: Break the Rules of Marketing to Build Luxury Brands (London and Philadelphia: Kogan Page).

15. Vigneron, F. and Johnson, L. W. (2004) “Measuring Perceptions of Brand Luxury,” Journal of Brand Management, 11/6 (July): 484–506.

16. Patrick, V. and Hagtvedt, H. (2009) “Luxury Branding,” in Handbook of Brand Relationships, eds. Deborah J. MacInnis, Joseph W. Priester and Choong Whan Park: 267-280 (New York: Society for Consumer Psychology and M.E. Sharpe).

17. Dubois, B. and Paternault, C. (1995) “Understanding the World of International Luxury Brands: The ‘Dream Formula’,” Journal of Advertising Research, 35/4 (July-August): 69-76.

18. Berthon, P. R., Pitt, L. F., Parent, M. and Berthon, J.P. (2009) “Aesthetics and Ephemerality: Observing and Preserving the Luxury Brand,” California Management Review, 52/4 (Fall): 45-66.

19. Kapferer, J. N. and Bastien, V. (2008) The Luxury Strategy: Break the Rules of Marketing to Build Luxury Brands (London and Philadelphia: Kogan Page).

20. Hagtvedt, H. and Patrick, V. (2008) “Art Infusion: The Influence of Visual Art on the Perception and Evaluation of Consumer Products,” Journal of Marketing Research, 45/3 (June):379-389.

21. Silverstein, M.J. and Fiske, N. (2003) “Luxury for the Masses,” Harvard Business Review, 81/4: 48-57.

22. Davis, A. (2013) “Louis Vuitton Perfectly Engineers ‘It’ Bag Frenzy,” The Cut – New York Magazine (comment), September 16, 2013, http://nymag.com/thecut/2013/09/louis-vuitton-perfectly-engineers-it-bag-frenzy.html.

23. Glaser, B. G. and Strauss, A. L. (1967), Discovery of Grounded Theory-Strategies for Qualitative Research, (Chicago: Aldine).

24. Goulding, C. (2002), Grounded Theory. A Practical Guide for Management, Business and Market Researchers, (London: Sage).

25. Strauss, A. L. and Corbin, J. (1990), Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques (Newbury Park: Sage).

26. Hudson, L. A. and Ozanne, J. L. (1988), “Alternative Ways of Seeking Knowledge in Consumer Research”, Journal of consumer research, 14/4 (March): 508–521.

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-100x70.jpg)