By Sean Culey

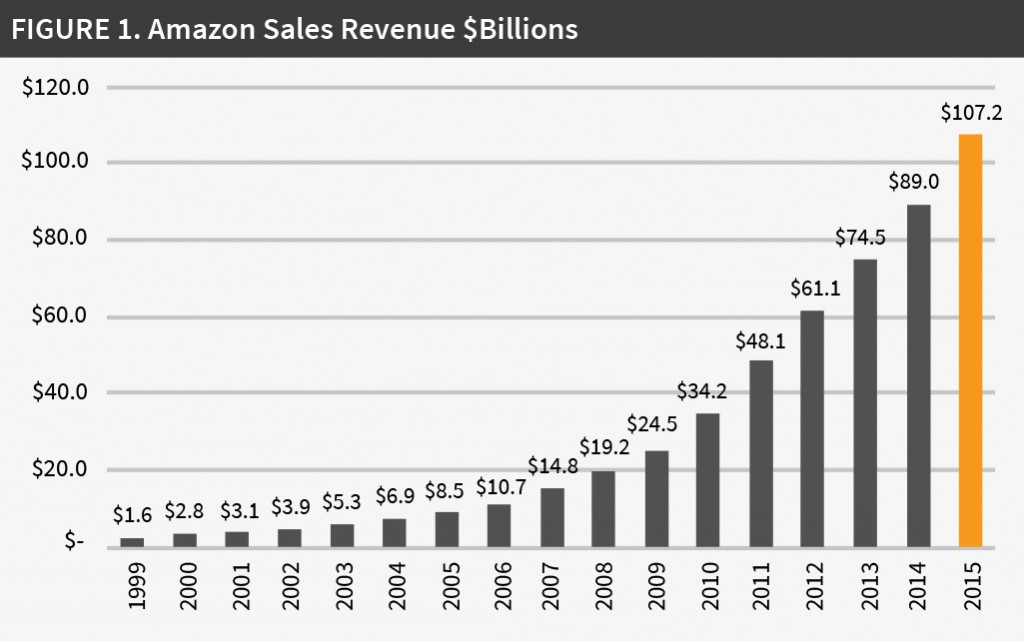

In just 20 years, Amazon has grown from an online startup focusing on selling books, to a devastating multi-platform, multi-industry technological disruptor, predicted to be worth $3 trillion by 2026. In his latest article, Sean Culey describes how the company is using its massive R&D fund to create a virtuous cycle of technological innovation that is outpacing Google, Facebook and Apple combined. Jeff Bezos’ goal of creating the “Everything Store” is nearing fruition, meaning that competitors – and nations – are now facing a relentless monopolistic giant, one that is aiming to control every aspect of the future global value chain.

On February 7, 2016, an average of 111.9 million people1 watched the televised coverage of the Denver Broncos’ 24-10 victory over the Carolina Panthers at Super Bowl 50, making it the third most-watched program in US television history. They would have also witnessed a world first; a Super Bowl advertisement by the online retailer Amazon, promoting its new voice-controlled home device called Echo.

Two weeks later, Amazon did something else surprising; they raised the minimum amount that non-Prime customers had to spend to qualify for free shipping by 40%, raising it from $35 to $49.2

These two actions were not unconnected, but well thought out strategic moves designed to realize Jeff Bezos’ grand vision of Amazon becoming the ‘Everything Store’. This article will explain how moves like these are swiftly moving Amazon into a checkmate position against not just other online retailers, but also logistics companies and suppliers worldwide.

Building The Everything Store

Back in 1994 during the early days of Internet, a job posting for Unix / C++ developers was issued on the Usenet group mi.jobs, looking for applicants to join a ‘well-capitalized Seattle start-up’. The poster was Jeff Bezos, and the start-up was Amazon. Bezos finished the posting with a quote attributed to Alan Kay; ‘It’s easier to invent the future than to predict it’.3

It’s a mantra Bezos has consistently followed. Amazon has already unleashed its creative destruction power against the publishing industry, completely redesigning the way people bought and read books. The incumbent booksellers and publishers were caught in the destructive side of the equation, creating casualties such as Borders, which went bust in 2011. To many, this is Amazon – an online retailer renowned for crushing suppliers, putting booksellers out of business and poor working conditions in its fulfilment centres.

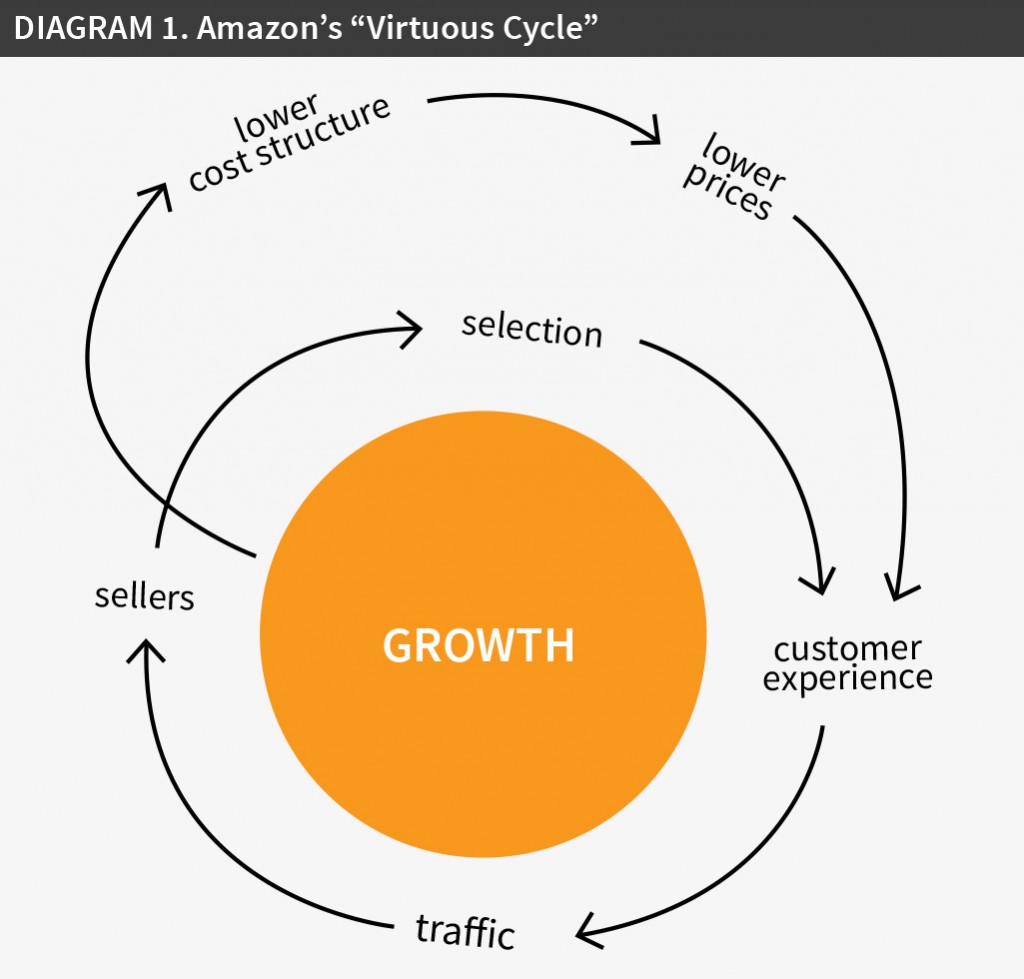

However there is much more to Bezos’ ambition than this, and those who are paying attention would have seen Amazon quietly introduce them, hiding in plain sight. The problem is, not many have noticed – and this may prove a fatal oversight. Bezos’ ultimate vision is to create ‘the Everything Store’, a retail destination where people can buy everything they want, when they want, at the price they want. However, visions are simply hallucinations unless they are backed up by action, and Bezos is a man of action. As Jim Collins detailed in his books,4 the great organisations are guided by an unchanging core principle while also developing a flywheel culture of continuous improvement and innovation focused on the customer. In Amazon, this flywheel is called the ‘virtuous cycle’, based on the three customer-centric components of price, selection and experience.

Diagram 1: Amazon’s ‘Virtuous Circle’

The circle works like this; Amazon initially attracts customers through the combination of low prices and convenient ordering. The lower the prices, the more customers are likely to visit their website. The better the customer experience, the more the customer is going to repeat that visit. More customers increase the volume of sales and attract more commission-paying third-party sellers to the site, further increasing choice while also allowing Amazon to get better utilisation out of fixed costs such as their fulfillment centers and website servers. This improvement in efficiency creates the opportunity to lower prices further, attracting more customer visits. As each component is improved, the synergistic effect causes the flywheel to turn faster.

Keeping the customer at the heart of the model and focusing only on those things that drive the flywheel forward has become the ‘unmoving principle’ at the heart of Amazon. As Bezos states; “I very frequently get the question: ‘what’s going to change in the next ten years?’ And that is a very interesting question; it’s a very common one. I almost never get the question: ‘what’s not going to change in the next ten years?’ And I submit to you that that second question is actually the more important of the two.

In our retail business, we know that customers want low prices, and I know that’s going to be true ten years from now. They want fast delivery; they want vast selection. It’s impossible to imagine a future ten years from now where a customer comes up and says, ‘Jeff I love Amazon, I just wish the prices were a little higher [or] I love Amazon, I just wish you’d deliver a little more slowly….And so the effort we put into those things, spinning those things up, we know the energy we put into it today will still be paying off dividends for our customers ten years from now.”5

Amazon actions therefore always support at least one aspect of this cycle. The decision to develop Amazon Marketplace and allow other retailers and suppliers to sell their wares through their website was questioned by the Amazon team, but not by Bezos. He realised that it would dramatically increase the number of sellers, increasing the choices available to consumers, which increases the number of visits, attracting more sellers, which again increases the choice. Meanwhile, Amazon ensures that it takes a percentage of every trade that takes place in this virtuous cycle of demand capture.

Locking in

E-commerce is fast approaching its tipping point, with US online sales increasing to $341.7 billion, an increase of 14.6% from 2014.6 However, that is still only 7.3% of total US sales, leaving a massive opportunity for those who can change the buying patterns of consumers from physical to online stores. It’s a challenge Amazon is taking on with gusto. The creation of a marketplace built around the virtuous circle principles of convenience, choice, and price have enabled it to overtake Walmart as the world’s most valuable retailer, with over 200 million items for sale on its website and the #1 choice for Americans to buy things online. A significant reason for Amazon’s continued growth is the level of strategic thinking applied to its supply chain strategy. One of the key components in this strategy is Amazon Prime.

In its Q4 2015 earnings report, Amazon announced that in 2015 paid Prime memberships increased by 51% globally, and 47% in the US – despite Amazon raising the cost of Prime in the US by $20 to $99 in March 2014. A January 2016 report by Consumer Intelligence Research Partners declared that 46% of the households in the US, now belongs to Amazon Prime. This number jumps significant for the upper middle classes, with 70% of households with annual income over $112,000 paying for Prime.7 Prime’s free shipping offer has been a major draw for consumers, with 47 per cent claiming that this was the primary reason for them signing up.8 Amazon added more than 3 million new Amazon Prime members globally in just one week at the height of the 2015 holiday shopping season, mostly attracted by the lure of free shipping.9

Free shipping and added value services such as Prime Music, Prime Video and Cloud storage draw customers into Prime, where they justify their subscription by ordering as many things as possible through Amazon. For those remaining non-Prime shoppers, the decision to raise the minimum shipping amount needed to qualify for free shipping, and increasingly slower delivery times for non-Prime orders make the alternatives less attractive. Both approaches are part of Amazon’s strategy to expedite the transition of the remaining households over to Prime membership.

Why is this so important for Amazon? Because as well as providing $99 upfront, creating cash flow for future innovations, Prime members also spend almost double the amount per year than non-members do. The average Prime household accounts for approximately $1,100 in purchases while non-members spend about $600. Prime members also tend to be more loyal, with 95% renewing their membership after one year. Amazon understands that the first click is the most important, and if, through the benefits of free shipping, they can persuade shoppers to start their purchasing decisions with a visit to Amazon, this immediately takes away page views from competitors, creating a huge advantage. On the internet, where your competition is only a click away, ensuring that you own the first click is crucial.

Amazon’s retail sales in the last 12 months accounted for $82.8 billion of this, whereas its nearest online competitor, Walmart, made only $12.5 billion.10 However, the opportunity is still massive for Amazon, as 92.7% of US retail activity, notably food and apparel, still takes place in traditional bricks-and-mortar stores.

That may all be about to change. Amazon’s virtuous cycle is about to shift into top gear.

Virtuous Cycle Part 1: Dramatically increase consumer selection

In 2015, Jeff Bezos announced that his goal is for Amazon to grow sales to $200 billion. To achieve this, Amazon is looking to expand both its fashion and grocery efforts, two huge markets that it has yet to nail (in 2015, its market share of online food and beverage sales was around 22%). However, the amount of groceries purchased online in the US is relatively small, representing only $33 billion out of $795 billion. Amazon is doing all it can to expedite the shift from physical to online by directly attacking the major grocery retailers.

In 2013, after completing successful trials in Seattle, Amazon began expanding its grocery delivery service Amazon Fresh to other cities, delivering around 20,000 items, including fresh produce, from local shops. This service is also being rolled out to the UK using the name ‘Amazon Pantry’, offering consumers a selection of approximately 4,000 grocery and household items.

The strategy is working. Back in 2012, Walmart was the undisputed ruler of retail and the third-most valuable American company. Its $444 billion in revenue was 16 times the revenue of Amazon and was equal to 3% of the US economy. However, in July 2015, Amazon’s market capitalisation exceeded Walmart’s for the first time. Nine months later and this gap has increased dramatically, with Amazon’s valuation rising to $294 billion and Walmart’s falling to $217.21 billion.

Amazon’s global intentions in this market became apparent earlier this year when they signed an agreement with UK supermarket chain Morrisons. This agreement provides Morrisons, which was a late arrival to online shopping, with access to Amazons logistical capabilities, while Amazon immediately gets access to Morrisons grocery customer base. Morrisons has already supplied 800 separate product lines – all tinned and packaged groceries – to Amazon, with its CEO, David Potts, stating that the availability of all its ranges via the Amazon Pantry service is ‘imminent’.11

The market approved. Amazon’s deal with Morrisons caused an immediate 6% rise in its share price, but a 9% drop in the value of Ocado, the online food distributor who has a 25-year contract to deliver Morrisons’ online deliveries. As Amazon quickly uses its new partnership to learn the UK grocery business, many, such as Credit Suisse and Goldman Sachs,12 have already stated that Ocado should just give up and let Amazon acquire it. By acquiring Ocado’s trucks, automated warehouses and customers it would immediately possess the physical capabilities necessary for Amazon Pantry to rapidly expand and steal customers from the other major grocery retailers such as Tesco, Sainsbury’s and Asda.

Although traditional grocers may not see sales migrate to Amazon right away, that luxury won’t last. By growing its Amazon Fresh offering, Amazon is preparing for a long fight in grocery. Becoming a grocery supplier not only expands the choice available to consumers, bringing more sales, but it could also make its business much more profitable due to frequency and density of ordering. People tend to buy groceries at least weekly, so getting them hooked on delivery justifies sending trucks out more frequently. Also, the wide variety of choices Amazon has, plus its increasingly intelligent recommendations system, draws consumers into purchasing non-grocery items that get shipped at the same time, adding sales while optimising shipping costs. It is also planning to move from grocery supplier to manufacturer, announcing that by summer 2016 it will produce and sell private label brands ranging from diapers to perishables.13

In 2013 Amazon began expanding its grocery delivery service Amazon Fresh to other cities, delivering around 20,000 items, including fresh produce, from local shops through Amazon.

Amazon is also taking this ‘distributor to manufacturer’ strategy and using it to make inroads into the highly lucrative apparel market. It acquired shoe retailer Zappos for a reason – and it wasn’t just for selling more shoes. Amazon studies categories to learn the business and identify consumer-centric opportunities. They then skilfully bring suppliers into their marketplace to understand the emerging trends and figure out how to capitalise in this area by differentiating through speed, convenience, price, reliability and service. Amazon’s Fashion CMO Jennie Perry declared that; “We’re in it for the long haul. We’re really invested in this industry”14 and backed up that claim by introducing seven private clothing labels, including Franklin & Freeman men’s shoes and Society New York women’s dresses, and sponsoring New York’s first-ever men’s fashion week.

Amazon’s US apparel business, including sales by third parties, is now forecast to rise from $16 billion in 2015 to $52 billion in 2020 according to Cowen & Co. and is predicted to surpass Macy’s as the biggest apparel retailer in the US by 2017.15

Virtuous Cycle Part 2: Reinvent the Consumer Experience

Towards the end of 2014, when most retailers were still struggling with offering a reliable 48-hour delivery service, Amazon trialled a new one-hour delivery offering in Manhattan called Prime Now. Using a Prime Now app, Prime members could order from a range of 25,000 items and have them delivered within one hour for $7.99, or within two hours for free. The service was available between 8 am and midnight, 24/7, raising the bar well beyond what most people thought was realistic – but it worked.

Consumers lapped it up, and the Prime Now trial was an immediate success. Within six months, full page adverts in the UK press announced that this one-hour delivery service was now available in London, Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool and Newcastle. Since then it has expanded to other areas across the US and the UK – including wealthier areas such as Surrey – showing how quickly Amazon learns. As previously highlighted the adoption and usage of Prime in upper-income areas is high (70%), probably because they are more likely to be cash rich but time poor, making it logical that Prime Now would be a winner in a wealthy suburban area like Surrey. To expand the benefits of Prime Now, Amazon has also introduced a one-hour restaurant delivery service in the US, with the intention to roll this out soon in the UK. Of course, Amazon makes a percentage of every meal ordered. On May 1 2016 Amazon extended Prime Now from an app to a web destination, allowing Prime customers to select one or two-hour delivery slots on PrimeNow.com.16

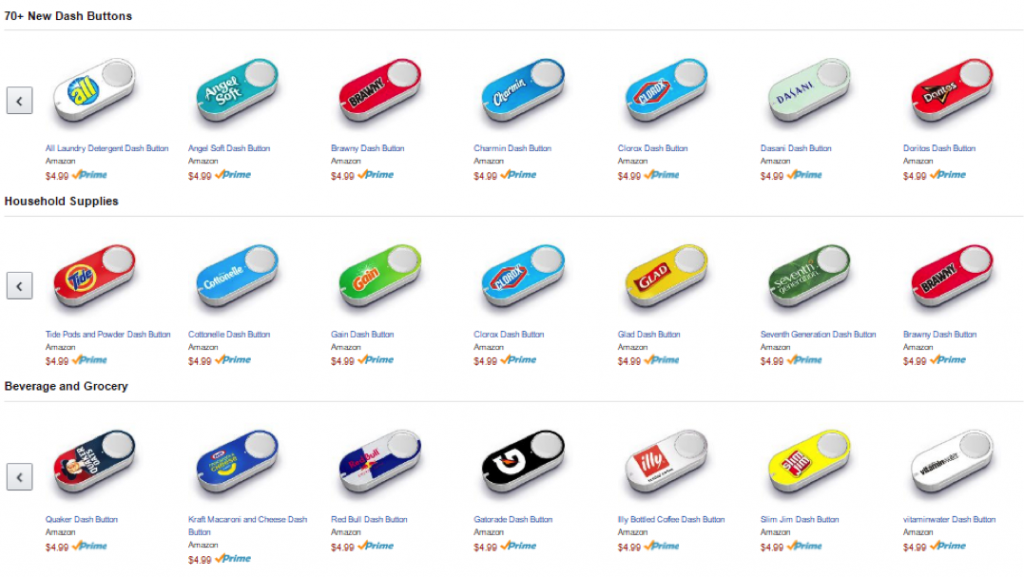

Back in 2014 Amazon also trialled two other innovative products with select US-based Prime customers – the Dash and the Dash Button. The Dash was a small handheld device that allowed you to order items by voice, which were then automatically added to your Amazon Prime account’s shopping basket. Not long after this, Amazon Dash buttons were launched, small branded Wi-Fi devices that you placed in your house and which allowed you to re-order essentials – such as toilet paper, coffee capsules and washing powder – simply by clicking each brand’s button.

There are now over 100 buttons for different items available, and in March 2016, Amazon announced a broadening of categories to include snacks, beverages, batteries, and more office products, including brands such as Charmin, Doritos, Energizer, Red Bull, Starbucks, Trojan, and Vitamin Water. Orders via the brand-specific Dash Buttons have grown by 75% over the first three months of 2016, and there’s now one taking place every minute.17 Dash Buttons cost $4.99 each, but they come with a $4.99 discount off your first Dash order, and so are essentially free.

Amazon Dash never went on sale – it was never intended to. It was an experiment designed to see whether people would accept the concept of ordering by voice (they did). Likewise, the purpose of the Dash button isn’t to sell Dash Buttons – it’s to establish whether people would appreciate the convenience of being able to ensure that they never run out of essentials by simply clicking a single button. The goal is to encourage more frequent and more regular retail purchases of essential goods from Amazon.

Then, in late 2015, Dash Replenishment Service (DRS) came online. DRS is the Dash Button without the button, introducing into the home the concept of connected, smart devices that replenish themselves. With as little as ten lines of code, manufacturers can embed automated purchasing capability into their devices.18 Currently, fifteen major manufacturers, including Samsung, Brita, GE, Whirlpool and Brother have installed ‘DRS’ capability into their devices, creating water filters that automatically reorder replacement filters, printers that reorder ink and washer dryers that reorder detergent.

The whole purpose of Prime, Dash buttons and DRS is to keep the consumer locked into ordering all of your frequently needed goods through Amazon’s shopping empire, erecting walls of convenience that prevent customers from even considering buying their coffee or condoms elsewhere. Which takes us back to Amazon’s killer move, and the Super Bowl advertisement of Echo.

Amazon Echo, Tap and Dot devices

Amazon Echo is an innovation emerging from Amazon’s Devices division, an outcome of their continuous experimentation to develop the ultimate consumer platform. At the heart of Echo is Alexa, a cloud-based AI system similar to Apple’s Siri. It can play music, reads the news, answer questions, and – critically – order stuff through Amazon Prime. Echo can also control lights, switches, and thermostats with compatible smart home devices, for example, Nest, WeMo, Philips Hue and Samsung SmartThings.

David Limp, SVP of Devices at Amazon, stated at a press event for Echo that; “What we’re trying to do is to build a computer in the cloud that’s completely controlled by your voice.” It’s found a market. In less than a year, Echo has become the best selling device on Amazon over $100, and Amazon doesn’t miss a beat, making Echo-compatible light bulbs, thermostats and electrical outlets recommended items when you select Echo on Amazon.com.

A Whole New Platform

Bezos’ understanding of the power of platforms is proving pivotal. Whereas the Kindle was a platform designed to expedite the transition from physical books to eBooks, the Echo is designed to transition people from ordering goods using the PC and smartphone, to just their voice. However, people would not be interested in a device from a retailer that just allowed them verbally buy things, and therefore Echo needed to be much more than just a consumption portal – it had to become the centrepiece of your home. Conversing with Alexa had to become a natural part of their daily activities; one they couldn’t do without. One where other companies would pay to have access to that platform. One that meant it became the ‘one device’ that ran their homes – claiming a huge ‘first mover’ advantage preventing any other devices from encroaching on this space.

Amazon, therefore, needed the right ‘hook’ to get consumers to buy it – and that hook was music. Data from beta testing uncovered that the most common activity people used Echo for was playing music. This finding encouraged the devices team to make this a more prominent feature, creating a reason for people to increase their frequency of engagement with Alexa. Amazon improved Echo’s speaker quality and song selection, enabling Echo to rapidly command 26% of the online speaker market, outselling established brands such as Sonos, Bose and Sony combined.19

Amazon has also understood that closed systems provide closed opportunities. The attractiveness of a platform depends on the number of things people can do with it, as the more benefits and applications a device has, the more likely people are to buy it. The more people who buy it, the more app developers and suppliers would want to work with it. Another virtuous cycle.

Amazon has therefore made Echo and DRS into open platforms. Manufacturers can easily make their devices DRS compatible by adding either a physical button into their hardware that when pressed reorders the consumables or by measuring usage and automatically reordering on behalf of the consumer through Amazon Prime. With Echo, Amazon has allowed developers to create ‘Skills’ (apps) that people can purchase to expand the capabilities of Echo, enabling it to interface with other devices with Echo or other platforms. There are currently more than 300 listed Skills available, from ordering pizza to 7-minute workouts. Spotify, Dominoes, Uber, FitBit and Capital One are just a few companies that have created Skills, and even car companies like Ford are planning to integrate their products with this new platform. Hence the Super Bowl advertisement campaign. As VP of Amazon Devices, Neil Lindsay, explained; “We’re showing Echo in this Super Bowl campaign because we think being able to control your lights, order a pizza, or listen to music with only your voice is magical, and we wanted to show that in action.”20

In April 2016, Amazon expanded its smart home reach even further with the release of Echo Dot and Amazon Tap. Dot is an extension of the original Echo, allowing users to have multiple access points to speak to Alexa in their home, and Tap is a portable speaker you can take with you that connects to a Wi-Fi connection or smartphone to play music on the go. Amazon Tap and Echo Dot extend Amazon’s smart home capability, providing a simple, easy way to connect devices and issue voice commands.

Echo, DRS and Dash are strategic masterstrokes; final building blocks in Bezos’ ‘Everything Store’ vision. They are also about to disrupt the retail industry in a way that their competitors probably do not yet understand or appreciate. Dash and DRS provide a way for a household’s regular needs to be replenished automatically, while Echo creates the ability for people just to verbalise their wants – and Prime Now provides a sub two-hour delivery service to both. In effect, consumers no longer need to shop anywhere other than Amazon for almost all of their commodity purchases.

To the vast majority of consumers and Amazon’s competitors, Echo is just a cool voice-controlled speaker. In reality, Echo has enabled Amazon to intertwine itself with the running of consumers lives, creating a continuous relationship with them rather than just a transactional one. Now they are focusing on dramatically increasing the number and variety number of these relationships, locking consumers into continually using it and in doing so creating in effect the ultimate convenience device. A platform that is constantly getting smarter and adding more functionality, one that allows the consumer to merely verbalise their needs – music, takeaway food, groceries, transportation – and for it to arrive as if by magic. A platform that has a hundred different ways to embed Amazon into your life – and of course a hundred new ways to make them money.

The first mover advantages this provides are enormous. As a website, where the competition is only a click away, Amazon is always at risk that the consumer may look elsewhere. Echo provides a way to secure consumer demand before they even go online, effectively making Amazon the first choice retail channel for the entire household. The genius behind Amazon’s platform model is that once the consumers are hooked on the ease of use of Echo, Prime itself becomes more valuable, securing its automatic renewal. Another virtuous cycle of creativity for Amazon, and a vicious circle of destruction for its competitors.

Amazon has therefore already won the Internet of Things (IoT) race while others are still talking about it. It’s a winner takes all model as people won’t want ‘two’ devices running their household. By becoming the ‘one device’ that runs the home Amazon has created more than just a new way to engage with customers – it has created a whole new platform that people are queuing up to use. A platform that also captures an enormous amount of data.

The Power of Data

In a 2014 New Yorker article on Amazon one line stands out; “Before Google, and long before Facebook, Bezos had realized that the greatest value of an online company lay in the consumer data it collected.”21

Echo’s Alexa is a cloud-based AI device that learns through use, collecting data as it goes; your data. Amazon has long used purchase data to drive replenishment strategies, offer recommendations and set prices – but with Alexa, it is about to capture more data than any other company combined. Using Echo and Alexa allows Amazon to capture data on what you buy, when you buy it, what music you like, what films and TV programs you watch, where you go, what pizza toppings you like – everything they need to drive their virtuous cycle of convenience. This data has enormous direct and indirect value to Amazon. Amazon already hinted at how much data Alexa captured when they reported the top Christmas songs people played through Echo and how often they used the timer function to help with cooking Christmas dinner.

Amazon is making a Faustian bargain with the general population; the sale of your privacy for convenience, choice & price. You want free music, free videos, TV programmes, free delivery, convenience and low price. Amazon wants to know everything about you and to be your sole retailer. It has therefore created the platform where you get what you want, but you have to sign up to what they want – for Amazon to capture enough data to become your personal ‘everything store.’ It is a bargain most are willing to make.

To process all of this data, Amazon has also used one of their other platforms, Amazon Web Services (AWS), to allow developers to use their Cloud based servers to build machine learning solutions that improve the quality of their predictive analytics. It’s proving advantageous. Amazon filed a patent in early 2014 for algorithms able to know what people wanted before they placed an order.22 With Echo and AWS, Amazon has both a robust audience, a ready-made data collection device and a flurry of developers rushing to put their services on its platform. Running Amazon’s website and servers is expensive, but they turn this overhead into a money making opportunity by offering third parties access to their spare capacity, creating another revenue stream for the company. It’s a profitable business. In 2015, Amazon Web Services generated $7.9 billion, with an operating income of $6B.

Virtuous Cycle Part 3: Dramatically reduce prices

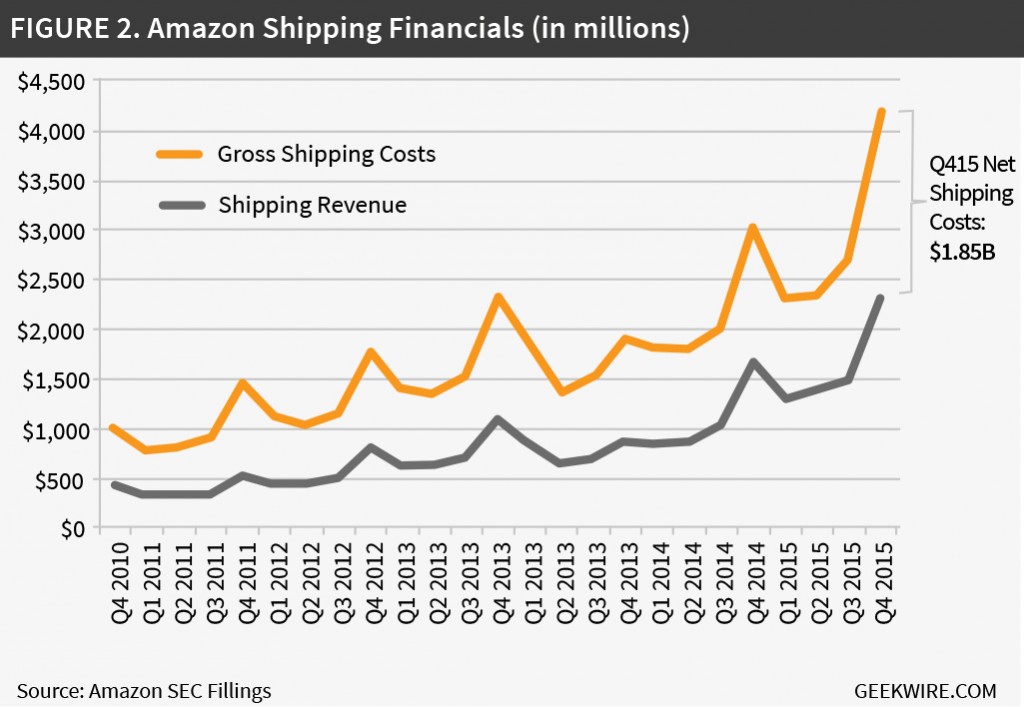

Amazons strategy of responsive supply has come at a major logistical cost. Amazon’s net shipping costs reached an all-time high of $1.85 billion during the fourth quarter of 2015, driven mostly by an extremely busy Black Friday and Christmas period, which meant that the 2015 costs surpassed $5 billion, a 19% increase on 2014.23

Amazon had taken actions to address the rising costs by raising the annual subscription cost of Prime from $79 to $99 in 2014, but it also knew that passing on any more costs to the consumer worked against the ‘low price’ element of its virtuous cycle. Likewise, if it squeezed the sellers and further it would limit the attractiveness of using Amazon as a marketplace, reducing the ‘choice’ element of the cycle. If Amazon was going to become the ‘Everything Store’, able to deliver items within one hour to its customers, it was therefore going to have to radically rethink its supply chain strategy. Here’s how it is planning to do it:

1. Get Control. In 2013, Amazon quietly announced FBA – Fulfillment by Amazon. With FBA, Amazon offered picking, packing, storage and shipping services for retailers selling on Amazon’s platform. It was a killer move. In one sweep Amazon set the agenda by making only FBA items available for Prime and Prime Now delivery, immediately making those items significantly more attractive to consumers and more profitable for Amazon. FBA was a key ingredient in making Prime a robust and successful offering; by only offering it on items they were in control of, they reduced the incidence of a supplier’s poor performance compromising their brand. Suppliers soon realised that Prime delivery items were much more desirable to consumers than non-Prime, and therefore were left with a choice to either join FBA or accept reduced sales. In addition to helping to sell profitable Prime relationships, FBA generated significantly more volume through Amazon’s systems, which lowered Amazon’s costs while generating revenue from competitors that were selling through Amazon’s marketplace.

2. Automate. For Prime, Prime Now and FBA to work, Amazon had to develop perhaps the world’s most advanced supply chain. It had to reduce the cost per item shipped while also dramatically improving the level of responsiveness and reliability. Enter the Kiva bots. Plagued by bad press about the working conditions in its fulfilment centres, Amazon needed a way to improve picking speed and accuracy, at lower cost. After acquiring Zappos.com and seeing how they used a fully automated robotics logistics picking system, in 2012 they purchased the company behind it, Kiva Robotics, for $775 million in cash. For two years it seemed like nothing was happening, but then before Black Friday 2014 Amazon announced that it rolled out 15,000 Kiva bots across its primary fulfilment centres in the US. The following year this had doubled to 30,000. Kiva robots are quicker, more accurate and allow Amazon to store 50% more inventory in each Kiva fulfilment centre because humans don’t have to walk the aisles. They also save Amazon a fortune. Each item costs Amazon $0.448 to pick using humans, but by using Kiva, this falls 47.6% to $0.213 per item. Amazon has now developed its own division, Amazon Robotics, to continually develop new and innovative ways to fulfil customer orders faster and more efficiently.

3. Go local. To achieve one-hour deliveries, Amazon had to localise their supply chain. Amazon needed to create a series of smaller fulfilment hubs in urban locations, able to hold enough inventory to meet the needs of the local Prime Now customers. It also needed to dramatically improve the level of algorithmic assistance it obtained to understand projected consumer demand, as getting it wrong meant that it would both fail its delivery promise, and quickly fill the urban fulfilment centres with inventory.

4. Create flexible alternatives. For Prime Now to work, Amazon needed to be able to deliver orders individually, rather than the usual next day approach of combining multiple orders in a shipment route. Buying this level of responsiveness from 3PL’s (who were already struggling) would be incredibly expensive. So what to do? Amazon firstly recruited cycle couriers to deliver non-bulky Prime Now orders in urban areas. Then it hit on a new way to expand its delivery force – Amazon Flex. Utilizing the gig economy model, Amazon now allows approved private individuals to become ‘delivery drivers for hire’, paying them $18-25 per hour to deliver Prime packages using their cars. Similar to Uber, drivers use an app to sign up for shifts to pick up packages from Amazon’s metropolitan warehouses and deliver them to customers’ doors. The drivers even developed and used additional software as a flex grabber to get them more deliveries and help them earn more profit at the end of their shifts. Amazon Flex is a great project overall, with the high number of jobs it will create for young adults trying to be diligent. The program is currently available in 14 cities across the US. This has also presented Bezos with an Uber-beating opportunity. Uber is basically just an app plus customer support, but one that is valued at more than GM24. However, its start-up costs ran into the billions. Amazon’s creation of the Flex platform could allow it to dramatically reduce both the start-up and driver incentive costs by combining ride-sharing with its package delivery service, providing Amazon with a powerful – and sustainable – competitive advantage.

5. Own your own trucks. Over the 2015 holiday period, it was clear that the 3PLs that delivers Amazon’s packages could not cope, expediting Amazon’s decision to take measures into its hands. Something Amazon is not even trying to hide anymore if this recent job posting is anything to go by; “Amazon is growing at a faster speed than UPS and FedEx, who are responsible for shipping the majority of our packages. At this rate, Amazon cannot continue to rely solely on the solutions provided through traditional logistics providers. To do so will limit our growth, increase costs and impede innovation in delivery capabilities. Last Mile is the solution to this. It is a program which is going to revolutionize how shipments are delivered to millions of customers.” Then, in December 2015, Amazon announced that it had purchased thousands of truck trailers to ship merchandise between its primary fulfilment centers and its more local warehouses. Amazon Fresh’s grocery service is a big driver behind this move, with Amazon purchasing a fleet of grocery delivery trucks to support this sector. By owning its own trucks, Amazon can ensure constant replenishment of the smaller Prime Now locations, able to travel in the middle of the night when the roads are less busy or during holidays – all things for which a 3PL would typically charge a premium.

6. Rethink the last mile. Cycle couriers and Amazon Flex are all temporary measures until legislation catches up with Amazon’s level of innovation, allowing them to automate the last mile with drones and autonomous vehicles. Amazon aims to dramatically reduce its shipping costs by using human-free methods, and has already been advertising Prime Air drone deliveries on US national television, highlighting that they have the technology ready and waiting. Delivering items at the cost of electricity would allow Amazon to offer lower prices than competitors using traditional delivery methods, creating more momentum for its virtuous cycle.

7. Control the whole international supply chain. Amazon doesn’t just want to be a last-mile deliverer; it wants to run it all. The real scope of Amazon’s intentions became apparent recently when leaked documents appeared that contained details about Amazon’s secret project ‘Dragon Boat’.25 The documents describe Dragon Boat as a “revolutionary system that will automate the entire international supply chain and eliminate much of the legacy waste associated with document handling and freight booking.” Dragon Boat is about to be officially launched as “Global Supply Chain by Amazon”; an aggressive expansion of its Fulfilment by Amazon services designed to create a global delivery network that removes the cross-border barriers for small merchants. It will put Amazon at the centre of a logistics industry that involves not just shippers like FedEx and UPS, but also legions of middlemen who handle cargo and paperwork associated with international trade.

This move means that as well as doing the outbound shipping, Amazon will also move goods directly from the supplier’s factories – which may be in China or India – to the fulfilment centre, effectively controlling, and making a profit from, the whole end-to-end logistics process. This direct ‘factory to consumer’ model will allow Amazon to bypass these brokers, amassing inventory from thousands of merchants around the world and then buying space on trucks, planes, and ships at reduced rates. Merchants will be able to book cargo space online or via mobile devices, creating what Amazon described as a “one click-ship for seamless international trade and shipping.” The transformation of FBA into ‘Global Supply Chain by Amazon’ creates a huge honey pot of a platform, attracting sellers to use this end-to-end offering, trapping them into selling through Amazon’s marketplace and devices. This not only lowers costs but more importantly, it gives Amazon direct control over the layers of the value chain, potentially transforming them into not just the world’s biggest retailer, but also the world’s largest distribution company. If successfully executed, it is estimated that this would create an entirely new $400 billion26 business model for Amazon – one that would be tough and costly to compete against.

In its latest 10-K, Amazon even changed its company description to a “transportation service provider”27 and is currently leasing 20 Boeing 767 freight planes to boost shipping speeds and increase capacity with the intention to increase this to 60.28 It has also received a license to expand into ocean freight and is reportedly in talks to purchase loss-making airport Frankfurt-Hahn, which is for sale, in order to create an inbound hub to aid with its plans to offer Prime Now one-hour delivery across several cities in Germany.29

In the short term, Amazon would continue to need companies like FedEx and UPS while they take their first baby steps along this path, which could create a false sense of security for those businesses caught in the cross-hairs, allowing them to remain in denial of what is happening. Even if they pick up on the threat, this may benefit Amazon as they could use it as leverage to renegotiate more preferential short-term shipping contracts, playing on the 3PL’s desire to make whatever money they can off Amazon before it runs everything.

Playing the Long Game

One of Bezos biggest achievements has been his relentless ability to stick to his vision and not capitulate to the lure of short term gains. The ability to go decades without turning a profit but still convince his shareholders to persevere with him and understand the long game. Once, when asked about Amazon’s revenue growth, Bezos couldn’t even remember the exact growth percentage. When asked why he didn’t know, he said: “I’m thinking a few years out. I’ve already forgotten those numbers.” As Bezos himself declared; “if you’re long-term oriented, customer interests and shareholder interests are aligned.” Amazon’s numbers back this up. Its Q1 2016 earnings report beat all estimates, recording its fourth profitable quarter in a row with $517 million in net income, compared to a $57 million loss it recorded in Q1 2015. Its year-on-year Q1 results saw operating cash flow rise 44% and revenue rise 28% to a staggering $29.1 billion.30 As a result of these numbers, Amazon’s stock price rose 12%, proving Bezos’ point.

A Kiva robot moves a rack of merchandise at an Amazon fulfilment center in Tracy, California.

Amazon’s retail virtuous cycle generated over $20 billion of this, growing 31% YoY compared to just 1.75% growth for the retail sector at-large (online and offline). The Q1 2016 earnings report also highlighted that the demand for Echo is so great that Amazon is struggling to keep up. Watching Amazon move its virtuous cycle into top gear in the US gives an indication of what its competitors in its other primary markets can expect in the future. It’s why Chamath Palihapitiya, founder and CEO of Social Capital, stated publicly at the Sohn Conference on May 4 2016 that he believes Amazon.com will be worth $3 trillion in 10 years.31

Bezos is exactly the type of entrepreneur that Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter was referring to when he described them and their innovations as the architects of the process of Creative Destruction. He has created a culture where people are continually experimenting, constantly trying to find new ways to drive its virtuous cycle, then quickly going big when something makes economic sense. Currently, it has a patent out to enable drones to use your phone’s GPS address to ‘follow you home’, a patent for 3D printing on an autonomous truck – effectively producing your goods while delivering them, and most interestingly, a move into physical stores – only ones that are human free. These stores use facial recognition cameras, sensors, and scanners to know when a person entered the store, when they removed something from a shelf and when they left with an item in her hand – capturing even greater levels of data for Amazon to process, analyse and use to rule the world.

The process of technological innovation involves complex relations among a set of key variables: inventions, innovations, diffusion paths and investment activities. Currently, Amazon is in control of all of these elements, being both responsible for the invention of new products and able to determine their marketability and reach a wide enough audience to convert into innovations. Then it can utilise its platforms to diffuse the innovation and plough money into their continued development without the short-term pressures that stifle other companies.

Aftershock! The Vicious Circle of Destruction

Amazon’s platform based business model is preparing to tighten its coils around its customers, sellers, competitors and partners. It is rapidly drawing more and more consumers onto Prime and Prime Now, either through its traditional marketplace or new platforms such as Echo, in turn forcing sellers to offer their wares to Amazon to fulfil, allowing Amazon to make a greater margin off every order sold. Competitors are now facing a monopolistic giant, able to control the supply chain and use its massive R&D fund to created new technological innovations that eliminate the humans, and their errors, from the equation. Likewise, as Amazon itself, and its sellers, choose to use Amazon’s global supply chain solutions, the ripple effect on the 3PL’s bottom line will significant. Finally, as Amazon increasingly moves into manufacturing, sellers will be forced to reduce their prices and innovate more simply to compete against their retail ‘partner’.

Amazon is becoming the ultimate gross margin killer. A company that, unlike traditional retailers like Walmart, doesn’t spend billions of dollars a year on share buybacks or offering dividends, instead choosing to invest in future growth. A company that continually challenges other retailers to try and remain competitive in a game where they keep changing the rules, forcing them to reduce their prices, knowing that it will drive their margins into the ground. They will then turn to their logistics partners, and ask them to reduce their costs to help, once again driving down the 3PL’s margins. They will challenge everyone to keep up, and they know very well that they can’t. Throughout all of this, Amazon continues to make money off every platform, from its cloud and web services through to its shipping services and online marketplace.

Amazon is changing the rules of the game, and for those that can’t keep up – or develop their own game changer – it’s game over. Not today. Not tomorrow. But soon. As Jeff Bezos himself declared “your margin is my opportunity”.

However, Amazon’s increasingly monopolistic position will raise some very big and important questions, and Amazon may find that its biggest challenge comes not from its competitors, but from national governments concerned at the wider social and economic impact of its plans. When Amazon negotiated agreements with several US states to delay the collection of sales tax in exchange for locating warehouses and providing jobs there, nobody presumably contemplated total warehouse automation. As companies start to fail and jobs are lost, how long will governments sit quietly by as Amazon acquires a monopolistic position, wiping out tax paying companies with tax paying employees, while it declares little taxable profit, choosing instead to reinvest in increasing levels of automation that feed its virtuous cycle of creative destruction?

About the Author

Sean Culey SCOR-P, FCILT, is a recognised strategic advisor, business transformation expert, keynote speaker and author focusing on helping companies develop compelling value propositions and strategies that get executed. Previously CEO of SEVEN, Sean has 25 years of global experience across numerous verticals, and is also CMO for an international software company and member of the European Leadership Team of the APICS Supply Chain Council. Sean will be delivering a series of workshops on the impact of disruptive innovations on business across the Asia Pacific region in August 2016, and his first book; Transition Point: Revolution, Evolution or Endgame? is due in 2017.

SCOR-P, FCILT, is a recognised strategic advisor, business transformation expert, keynote speaker and author focusing on helping companies develop compelling value propositions and strategies that get executed. Previously CEO of SEVEN, Sean has 25 years of global experience across numerous verticals, and is also CMO for an international software company and member of the European Leadership Team of the APICS Supply Chain Council. Sean will be delivering a series of workshops on the impact of disruptive innovations on business across the Asia Pacific region in August 2016, and his first book; Transition Point: Revolution, Evolution or Endgame? is due in 2017.

References

1. http://variety.com/2016/tv/news/super-bowl-50-ratings-cbs-third-largest-audience-on-record-1201699814/

2. http://www.cnbc.com/2016/02/22/amazon-raises-free-shipping-minimum-for-most-orders-to-49-dollars.html

3. http://techcrunch.com/2008/04/29/its-easier-to-invent-the-future-than-to-predict-it/

4. Jim Collins; ‘Built to Last: Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies’; 1994, ‘Good To Great: Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap…And Others Don’t’; 2001, ‘Greatby Choice: Great by Choice: Uncertainty, Chaos, and Luck–Why Some Thrive Despite Them All’; 2011

5. Amazon Web Services: 2012 Fireside chat with Amazon Founder & CEO Jeff Bezos and CTO Werner Vogels; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O4MtQGRIIuA#t=05m10s

6. https://www.census.gov/retail/mrts/www/data/pdf/ec_current.pdf

7. http://uk.businessinsider.com/amazon-prime-penetration-by-household-income-2016-4?r=US&IR=T

8. http://fortune.com/2016/02/22/amazon-shipping-non-prime/

9. http://www.geekwire.com/2015/amazon-adds-3m-new-prime-members-in-one-week-in-december/

10. http://fortune.com/2016/05/11/retailers-stocks/?xid=yahoo_fortune

11. http://www.retail-week.com/sectors/grocery/morrisons-to-start-selling-goods-through-amazon-imminently/7007266.article

12. http://uk.businessinsider.com/credit-suisse-ordered-a-box-of-goods-from-amazon-pantry-and-says-ocado-should-be-acquired-2015-11

13. http://www.wsj.com/articles/amazon-to-expand-private-label-offeringsfrom-food-to-diapers-1463346316?cb=logged0.29457892638318417

14. http://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/intelligence/amazon-fashion-playing-the-long-game

15. http://fortune.com/2015/07/20/amazon-macys-clothing/

16. http://recode.net/2016/05/02/amazon-prime-now-web-browser/

17. http://www.theverge.com/2016/3/31/11336362/amazon-dash-button-new-brands

18. https://www.amazon.com/oc/dash-replenishment-service

19. https://www.1010data.com/company/blog/detail/can-you-hear-me-now-the-surprising-success-of-the-amazon-echo

20. http://www.digitaltrends.com/cool-tech/amazon-first-super-bowl-ad-campaign/

21.http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/02/17/cheap-words

22. http://mashable.com/2014/01/21/amazon-anticipatory-shipping-patent/

23. http://www.geekwire.com/2016/amazons-net-shipping-costs-top-5b-for-first-time-fueling-push-to-build-out-its-own-delivery-network/

24. http://www.nasdaq.com/article/uber-is-higher-valued-than-gm-ford-and-most-of-the-sp-500-cm551162

25. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-02-09/amazon-is-building-global-delivery-business-to-take-on-alibaba-ikfhpyes

26. Comment from Robert W. Baird analyst Colin Sebastian

27.http://www.businessinsider.de/amazon-calls-itself-a-transportation-service-provider-2016-1?r=US&IR=T

28. http://theloadstar.co.uk/blow-express-carriers-amazon-leases-20-767fs-eyes-atsg-share-deal/

29. http://theloadstar.co.uk/dont-turn-back-amazon-eyeing-frankfurt-hahn-airport-buy/

30. http://www.techinsider.io/amazon-earnings-q1-2016-2016-4

31. http://www.cnbc.com/2016/05/04/hedgie-palihapitiya-sees-amazon-worth-3-trillion.html