A large number of businesses have a gap between the espoused strategy and what actually happens day by day. So much so that it even has its own phrase in the consultancy world – “the rift between the rhetoric and the reality”. In this article, John Sutherland discusses how to bridge the gap between the operational and the policy cycle and to achieve brilliant senior team work in organisations.

Dave was the fifth CEO in the business in as many years. Would he last? They had written his name on his office door in chalk so he was not off to the best start. But Dave was resilient and up for a challenge. Just as well, as it turned out.

Taking Stock

Dave did the sensible thing and took two months to understand the business he had taken on. Understandably, his pressing question was why had the previous four CEOs been asked to step down? The Board told him they were not “up to it” but what “it” was had never been specified to his satisfaction. Something was off and he smelt a rat. He asked me to help him flush out the problem and fix it at source. The clock was ticking for his first six-month review.

The problem, it turned out, was two fold. Firstly, there was a senior person on the team, Barry, who had been the first CEO, who was the technical “grandfather” of their process. He did not want a boss and did his own thing, regardless of decisions made by the senior team. Secondly, senior team work was dire and was failing to provide the leadership the business needed to pick itself up and come out of the downturn, sunny-side up.

A Business Cannot Have Two Heads

First things first. A business can not thrive with two heads. It never works well. You have to be able to achieve an agreement as the senior team and hold the line. Disagreeing strongly behind closed doors is fine, but once the doors open there has to be agreement, coherence and compliance. Barry had informal networks that by-passed the formal management controls and confused people in the engineering shed. Who should they listen to? But, because he was the technology founder, the previous three CEOs had felt unable to remove him, for fear of missing a critical technology input, going forward. Dave’s understanding was that they needed to maximise the commercial value of their current technology, not develop more, and drive to an exit for their investors, not continue their history of R&D spend. So Barry left and a major handbrake on progress was released.

Senior Team Focus

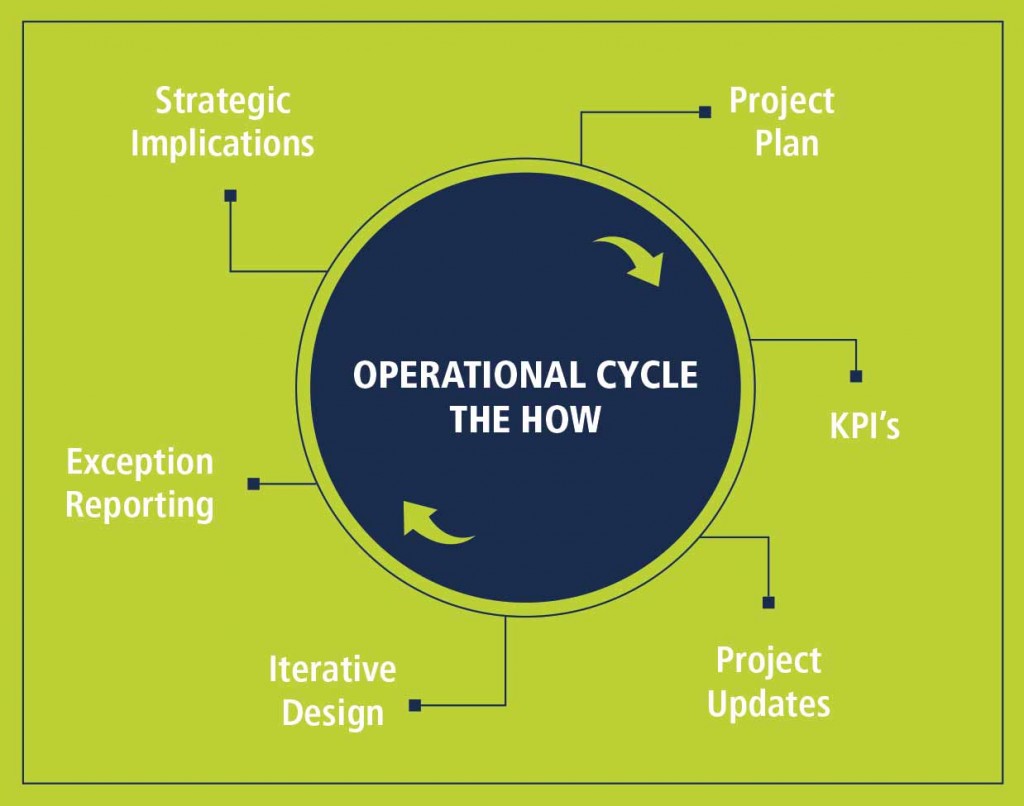

The second problem proved to be more tricky to fix. The meetings had become mired in operational detail and were viewed by all as not adding value. They were also incredibly boring. At the first meeting I attended there were 10 people sitting round a large table taking turns to give an update on progress (or lack of progress) on their monthly objectives. Death by PowerPoint was rampant, so we drew breath. They were in the operational cycle of the strategic process map. (see operational cycle model) Let’s be clear. They knew what their strategic objective was – it was to make the current technology commercially successful and head towards an exit from their investors in three years. But in the room you could be forgiven for thinking that the main focus of the business was to talk about the lack of progress against the plan on 27 highly tactical objectives, each in massive detail.

The Operational Cycle

After twenty-five years in consultancy work the biggest surprise to me is still the degree to which senior teams (around the world) spend a disproportionate amount of time in the operational cycle. This is the phase where we are focussed on putting into action the plans and objectives that were set by the CEO/Board/Senior Team. It is the “doing” phase of the business cycle where we work in the business, not on the business. And there is nothing wrong with that. We all need to expose our strategy to the risk of being successful by taking intelligent action with the resources available. But by itself it is not enough. There has to be a balance between doing what we said we would and keeping half an eye on refining our approach and our aspirations for the future, aka the Policy Cycle.

Some businesses get stuck in an operational loop. Marc’s was a case in point. Every quarter they heroically managed to just about hit their forecast, patting themselves on the back for their efforts. Better then not hitting the numbers, as we know, but they were dismayed when I pointed out to them that fighting their way out of a revenue gap at the end of every three months was not the same thing as leadership. They were in constant catch-up mode. Yes, they were “on plan” (after a fashion) but the medium-term future looked like more of the same – a frantic rush towards a number that always seemed to be impossible to hit.

Marc’s division was a striking case but take a moment to check on your own team work focus. What percentage of your meeting time is given over to project updates and operational reporting by individual directors/managers? For many businesses it is over 75%. And in these businesses, when we ask where the Policy Cycle work is, they point to items on the agenda that reference future facing themes. The problem is that they never quite seem to find the time to get to these items because the urgent supersedes the important, time after time, and the future facing item is yet again deferred for a few more meetings, before dropping off the agenda altogether a few months later. Marc’s team meetings got caught in a common pattern of hacking through the jungle of operational undergrowth. From time to time we need to climb a nearby tree to check that we are still heading in the right direction. “Wrong jungle” is not the cry you want to hear when you are working all the hours possible and your family is complaining that you are more like a lodger then a parent.

The Policy Cycle

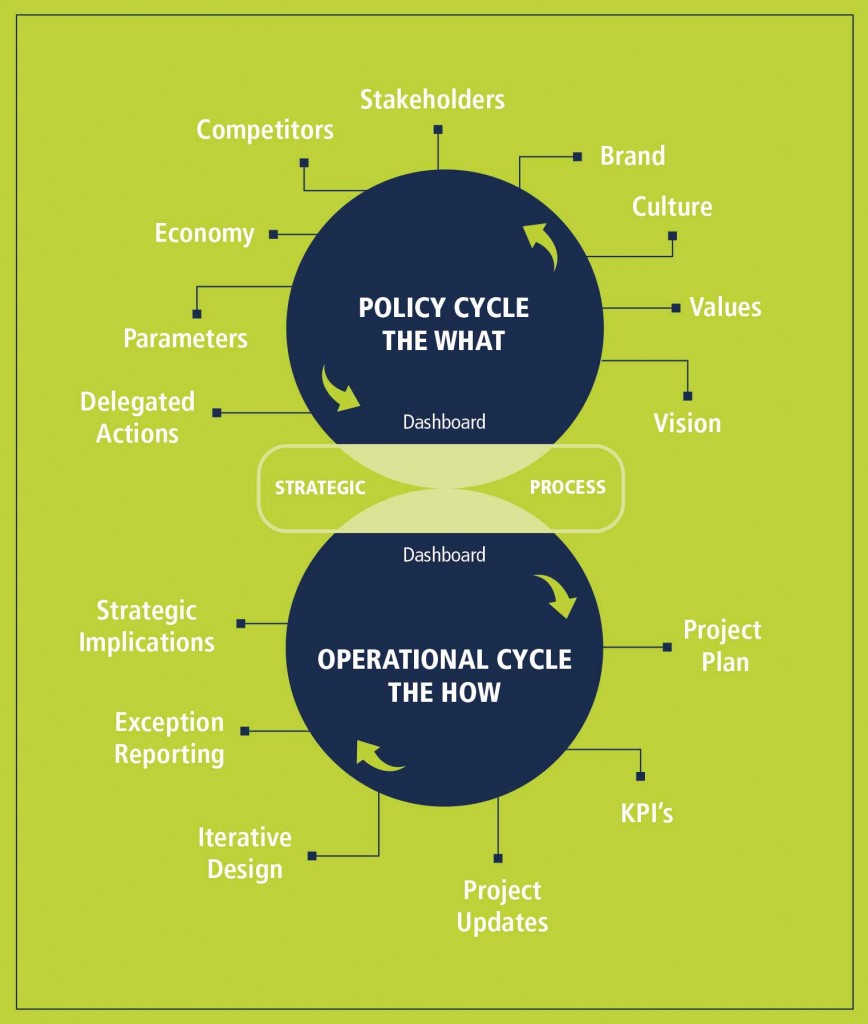

At this stage it is all too easy for a senior team to make a classic mistake, one that Dave was keen to avoid. An off-site is called to re-set strategic direction and the senior team disappear to their favourite hotel for a couple of days of perspective setting and business planning. Nothing wrong with that, in and of itself. The problem comes in the disconnection that often follows the off-site. In Dave’s organisation they had become used to the senior team going off-site. They did it twice a year and had done so for the previous three years. The problem was that it was as if there were two different worlds. One world, at the hotel, where pristine business thinking took place, considering the vision (a statement of a desired future some 3-5 years out with an objective outcome measure so we know if we are making progress) and the emerging strategy (an unfolding plan on how best to achieve the vision with the resources available and in our market context). There were some beautiful ideas discussed and agreed in those previous years but they were disconnected from the real world of the business, where work carried on as usual. The senior team would come back, gleaming with delight and clarity, but quickly became frustrated by the lack of real change that followed. A few months later and, once again, the operational urgent had displaced the strategic important and the next off-site was planned to re-set the focus. Net result: no actual change in the business. And that was the second challenge Dave had inherited. (see separated operational and policy cycle diagram)

Dave is not alone. A large number of businesses have a gap between the espoused strategy and what actually happens day by day. So much so that it even has its own phrase in the consultancy world – “the rift between the rhetoric and the reality”. All talk and no action, in other words. Frustrating all round. The senior team are annoyed that the rest of the business is failing to catch up. The rest of the business is frustrated that the senior team appear to live in their own fluffy cloud, floating above the real world of the daily grind. A match made in hades.

The Double-loop Model

It was Chris Argyris who first introduced the world to the idea of joining these two worlds together in an intentional learning loop, back in the 1970s. Sometimes old ideas are the best. His first notion was the most compelling and straightforward. We know that putting a plan into action is going to bump into problems. It does not work to simply to hatch a plan; you have to adapt as you learn what works. So Argyris suggested we focus on these deviations from the plan as a process of intentional learning. Each time we fail we learn a little more. Every cycle of learning helps us refine our approach until, eventually, we gain mastery in the delivery of our strategy. Like all revolutionary ideas it is at once elegant and profound. Take the very problems that frustrated senior teams in the past and convert them into a continuous improvement loop. Brilliant. (see double loop model)

Armed with this novel idea senior teams could come back from their off-sites with coherent direction, knowing full well there would be a steep learning curve on how to make this work in practice, and then set about ensuring their organisation was agile enough to carry on adapting itself until the path forward became credible, practical and actionable. Having set delegated actions for the organisation they were alert to feedback from the operational cycle on how to achieve their objectives in the most time-effective way. You have to go round the whole figure of eight policy and operational cycles many times, before the way forward becomes clear.

As Dave told his team, we know we need to drive the commercialisation of our current technology but we have yet to discover how to do this really well, so our primary task is to learn. Yes we want to make sales but the highest priority is rapid learning. And that was when the organisation tilted on its axis. We all felt it. Thereafter, his senior team meetings were buzzing with debate about what was working and, equally importantly, what was not working. Rather than get lost in the operational detail of each project, as they had before, they trained themselves to stay in the shaded area between the policy and operational cycles, where they held the tension between their high level vision and their current reality. And that takes some practice to achieve. Many teams “fall asleep” and confuse intentional rapid learning with merely completing a set objective. The former always sharpens your ability to elegantly achieve your vision. The later merely ticks off another task on the to-do list. Just another busy fool day brewing. Staying in the shaded area is strategic process; the unfolding dance between the future we are creating and the current reality we are dealing with; and that, when achieved, is brilliant senior team work.

As for Dave he has settled into the CEO role and now has the full backing of his Board. The business has transformed under his leadership and they are on course for their exit within 18 months. The day he replaced his name in chalk with a proper printed sign he called me. That was a fun call.

About the Author

John Sutherland is the Director of Strategic Resource, which assesses and develops senior teams in order to support them achieving their business plan. He is also the Director of the Leadership Initiative, which provides bespoke in-house programmes focussed on the specific skills required for each unique organisation.

John Sutherland is the Director of Strategic Resource, which assesses and develops senior teams in order to support them achieving their business plan. He is also the Director of the Leadership Initiative, which provides bespoke in-house programmes focussed on the specific skills required for each unique organisation.

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-100x70.jpg)