By Carlos Rey Peña and Joan E. Ricart

What is strategy? In this article, the authors view strategy as a discipline that harmonizes business model innovation with company principles and simultaneously meets the requirements of market demands. Their aim is to narrow the gap that currently exists between the theory and the practice of strategy.

Einstein said that everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler. Company strategy is one of those subjects that is often explained in a manner that is either exceedingly simple or overly complex. Some scholars, such as Porter1, view strategy as “the creation of a unique value proposition.” Others, including Hamel2, argue that strategy is the expression of ambition in the mission statement. For Rumelt3, strategy is a question of knowing how to develop key resources and then use those resources to generate and capture value; for Teece4, strategy is a dynamic method of combining and developing capabilities. For our purposes, strategy is defined as “the choice of a desired future for a company and the manner in which this future will be achieved.”5 This definition – simple to explain but difficult to implement – identifies the distinctive elements of a strategy. First, strategy is a choice. It encompasses choosing objectives, setting priorities, defining what we want to be and what we do not want to be. Second, strategy refers to the future; this clearly implies uncertainty and often means changing or departing from an established strategy. Finally, strategy is not only a desire, a goal, or a purpose; it is a path, a platform, and a specific indication about how we will achieve our desired future – which means that a strategy must also be realistic in terms of feasibility.

Despite the numerous efforts to define strategy, we are currently faced with a significant gap between the theory of strategy and its practice. The underlying problem is that the science of strategy endeavors to explain why some companies succeed and others fail – which is why there are so many perspectives and levels of analysis – whereas the practice of strategy seeks to identify courses of action that will solve problems and take advantage of opportunities. Put another way, the practice of strategy requires specific solutions for real-life situations.

An approximation to strategy that helps to close the gap between theory and practice is a concept called the logical method, i.e., the logical manner by which people make strategic choices. Because strategy is based on choices, we can distinguish three methods or types of strategic logic: analytical logic, institutional logic and systemic logic.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]The first, analytical logic, tries to understand the reality by focusing on its different elements or variables and establishing causal relations between them; e.g., “an increase in customer satisfaction of 10% leads to a 6% increase in market share.” The analytical logic uses empirical evidence or estimations of the behaviour of variables to reach conclusions. It tells us what we should do at (A) to lead to a determined consequence (B).

The second method, institutional logic, considers the characteristics of organizational identity; in other words, it tells us what we should do according to the principles and values of the company. Using this type of logic, the subject asks him or herself: “What should a company like ours do in such a situation?” The subject reaches a conclusion by connecting the situation to the values and beliefs that compose the identity of the organization and then acting accordingly6. It is commonly assumed that strategies are always developed based on analytical logic, but if we investigate what actually occurs in companies, we find that institutional logic is also very frequently employed7.

The third method, systemic logic, is also frequently employed, despite not always consciously. Systemic logic uses a mixture of experience and intuition to establish holistic explanations of the reality; for example, “the key to success in the automotive sector is having a strong brand.” Systemic logic goes beyond analytical and institutional logic by focusing on understanding the “whole reality” without being bound by the barriers of quantifiable data or by the characteristics of the organizational identity.

Strategic Perspectives: The SIA Model

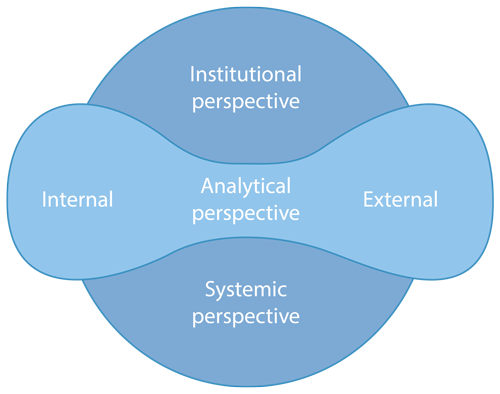

To understand strategy, we must recognize that it comprises three logics (analytical, institutional and systemic) and that each of these logics is also an independent source of strategy perspectives. Therefore, we can distinguish three strategic perspectives: analytical, institutional and systemic, which represent how the practice of strategy develops (see Figure 1).

Analytical perspective is based on explicit information that we receive from reality and is developed deliberately through the conscious analysis of the situation. The raw material for this perspective includes hard data, the trends of economic variables, market forces, efficiency curves, cost-benefit analyses, etc. The analytical “strategies” derived from this perspective are simple, specific, and presented in a prescriptive way. In general, analytical strategies view the company’s surroundings as an economic-competitive reality that can be analysed and predicted through models such as Porter’s forces, cost-benefit analyses, experience curves, decision trees, etc. Analysis is the key to this type of strategy, and development and implementation are usually viewed as separate and consecutive processes.

The analytical perspective has two basic dimensions: external and internal. The external dimension refers to an understanding of the company’s environment (sector, competition, markets, threats, opportunities, etc.) and the choice of where and how to compete. The internal dimension focuses on the company’s resources and capabilities, the processes and structures that promote their development, and the identification of internal strengths and weaknesses. The type of strategy derived from the analytical perspective is the business plan, which includes the two dimensions – external and internal – and establishes the course of action to be followed, with consecutive deployment of objectives, development of competences, process reengineering, or project planning.

Institutional perspective is generally expressed through “statements”, such as the company’s credo, mission, vision, values, purpose, etc., but this statement is only a symbolic representation of the institutional perspective’s true scope. It develops primarily at a subconscious level and is generated through socialization and the internalization of beliefs or modes of thinking regarding the general principles that should govern the company’s activities and stakeholder relationships. Put differently, institutional perspective can be understood as the company’s identity with respect to those parties with which it relates (clients, consumers, shareholders, employees, suppliers, society, etc.) The most complex aspect of this perspective is that it generates implicit strategies, but this is not to say that implicit strategies cannot be influential. Indeed, when no company strategy is explicitly defined (a phenomenon that occurs in companies more frequently than we think), the institutional perspective provides a default strategy. Because institutional strategy resides in people’s beliefs, its development and implementation are in fact the same process. The typical form of strategy derived from the institutional perspective is known as business principles, which are commonly represented metaphorically with slogans, declarations and symbols.

In addition, the institutional perspective motivates people to place the company’s interests ahead of their own and promotes a long-term outlook. If a company has no long-term institutional perspective, it risks the adoption of opportunistic short-term strategies characterized by changing and contradictory objectives, which damages the institutional health of the company and can destroy even successful businesses.

Systemic perspective: the systemic perspective is developed through a profound knowledge about reality that allows the establishment of valid hypotheses regarding the fundamental aspects of the market and the company itself. The raw material of the systemic perspective is a mixture of conscious and unconscious knowledge based on experience and intuition; it is developed through processes that may be called semi-deliberate, because they are not always controlled and planned. The systemic perspective is generated “in the mind” of the strategist, and is usually presented in a broad or non-specific manner in the form of ideas, models or reality maps. In this perspective, development and implementation are interconnected because implementation is a part of the development process. A typical format for strategies influenced by this perspective is the business model, which may be represented by canvases or graphics that explain reality8.

A business model establishes the general framework for a company’s actions. It describes what is truly important for the company and identifies the key aspects of company strategy. It should identify what differentiates the company from its competitors, how the company creates or destroys value and the main factors that contribute to company value. In fact, the business model reflects the strategy that has been conducted up to the present moment and thus incorporates all implicit knowledge not only about the company’s past choices and but also about their consequences9. If a company does not understand its business in a systemic way, it will be difficult to define successful strategies. As stated by Richard Branson, “the biggest risk any of us can take is to invest money in a business that we don’t know”.

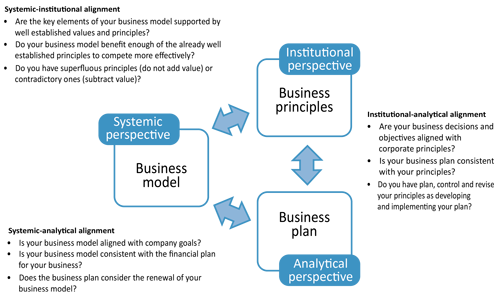

The integration of these three types of strategic logic – systemic, institutional and analytical – is represented in what we call the SIA model (see Figure 2). This model proposes a concurrent method for addressing the three types of strategic logic and establishes the internal alignment that should govern their integration. By addressing fundamental questions about the alignment of the three perspectives (as shown in the figure), the model reflects the relationship between them and illustrates the need to establish a common connection. Although each type of strategic logic achieves its fundamental function and is addressed in turns, together, they compose a single unit.

Competitive Advantage and Strategic Inconsistencies

However, a detailed analysis of successful companies shows that success is seldom achieved based on superior performance in only one of the three strategy types. For example, in the case of IKEA, its innovative business model – designing its own furniture, customer assembly, vertical integration into its own retail stores, and providing immediate delivery and low prices – has been accompanied by an ambitious business plan and solid institutional values, such as humility, courage and enthusiasm, based on the company’s stated mission, namely, creating “a better everyday life for the many people.” In our opinion, IKEA’s primary competitive advantage is not its business model, which other companies have copied without significant success, but the alignment and combined excellence of the three types of strategic logic—systemic, institutional and analytical — that has allowed IKEA to flourish for the past 50 years without any serious threats to its competitive position.

The alignment of and excellence in the three types of strategic logic can also be seen at Google and Johnson & Johnson. Like IKEA, each of these companies has a detailed business plan that tracks and promotes its growth; strong, deeply rooted institutional principles; and an innovative way of expressing its business model. These attributes have helped Google and Johnson & Johnson to beat incumbent businesses and/or to deter the entry of potential competitors. The lesson we have learned from these and other strategic success stories is that when analytical, institutional and systemic strategies are consistent and mutually support each other, a company’s ability to maintain and renew its competitive advantage is strengthened.

But if the internal support between strategic logics fails, the company suffers strategic inconsistencies. A strategic inconsistency occurs when a chosen strategy is logical and consistent within one type of strategic logic but inconsistent with one or both of the others. Examples of strategic inconsistencies can be a low-price strategy at a company with a premium business model; repeated layoffs at a company whose institutional strategy is based on trust; or a stated mission of “exceeding client expectations” at a firm with a low-cost business model. It is not a question of whether these business decisions are “correct” or “incorrect.” It may be that a company that has historically employed a premium business model must reduce its prices to survive, but in this case, the company should also adapt its business model to the new price strategy. A company based on a culture of trust may need to implement multiple layoffs, but if so, the company should also rethink its mission statement to maintain its institutional credibility. Strategic inconsistencies create problems for companies because they leave “negative footprints,”10 which ultimately lead to costlier, slower, and uncoordinated strategic decision-making, which damages the generation and sustainability of new competitive advantages.

Developing Strategy

Some time ago, we conducted a strategic reflection exercise by applying the SIA model to a divisional management team of a multinational energy company. Using a strategy canvas, we delineated the different elements of the company’s business model and the business models of its main competitors. Next, we then redefined the mission, vision and values, taking care to ensure that the company’s principles were truly aligned with its business model. Finally, we reviewed the company’s objectives and budgets and conducted scenario analyses that reflected the new strategic reality and its implications for the development of resources and capabilities. At the conclusion of this exercise, the managers were enthusiastic and demonstrated a common commitment to implement various changes in their respective areas of responsibility.

However, the most interesting revelation came in the months that followed. The speed and agility with which changes were implemented – even changes in organizational culture – greatly surprised the group of managers. An undertaking that previously would have entailed a two- or even three-year change management process was completed in just a few months. It is in this context that we learned that there are significant differences between defining a strategy and then coordinating it within the team and defining a strategy within the team that from the outset compiles and coordinates the various types of strategic logic and the contributions of each team member. The SIA model is the seed from which alignment between the various areas and functions of the company grows. As a result, company strategy is no longer a disjointed set of partial strategies derived separately by the HR, finance, production, marketing, and communication departments; instead it is a single, unified approach that includes and coordinates the relevant input from each department in a manner that generates a competitive advantage for the company.

In summary, whether in a team setting or individually, strategic thinking must always integrate the various types of strategic logic in a coherent manner. It is necessary to view strategy as a discipline that harmonizes business model innovation with company principles and simultaneously meets the requirements of market demands. In this way, we will acquire a better understanding of what strategy is and will be able to narrow the gap that currently exists between the theory and the practice of strategy.

Carlos Rey Peña is Professor of Strategic Management and Director of the Chair “Management by Missions and Corporate Governance” at Universitat Internacional de Catalunya (UIC). He is Business Strategy and Change Management consultant for companies such as Sony, Repsol or Bristol Myers Squib. He is co-author of Management by Missions, and other books and articles on strategy, leadership, and change management.

Carlos Rey Peña is Professor of Strategic Management and Director of the Chair “Management by Missions and Corporate Governance” at Universitat Internacional de Catalunya (UIC). He is Business Strategy and Change Management consultant for companies such as Sony, Repsol or Bristol Myers Squib. He is co-author of Management by Missions, and other books and articles on strategy, leadership, and change management. Joan E. Ricart is a Fellow of the SMS and EURAM, Joan E. Ricart is also the Carl Schrøder Professor of Strategic Management and Chairman of the Strategic Management Department at the IESE Business School, University of Navarra. He was the Founding president of the European Academy of Management (EURAM) and President of the Strategic Management Society (SMS). He has published several books and articles in leading journals as Strategic Management Journal, Harvard Business Review, Journal of International Business Studies, Econometrica or Quarterly Journal of Economics.

Joan E. Ricart is a Fellow of the SMS and EURAM, Joan E. Ricart is also the Carl Schrøder Professor of Strategic Management and Chairman of the Strategic Management Department at the IESE Business School, University of Navarra. He was the Founding president of the European Academy of Management (EURAM) and President of the Strategic Management Society (SMS). He has published several books and articles in leading journals as Strategic Management Journal, Harvard Business Review, Journal of International Business Studies, Econometrica or Quarterly Journal of Economics.

References

1. M. Porter, “What is Strategy?,” Harvard Business Review (November 1996).

2. G. Hamel, “What Matters Now,” (Jossey Bass, 2012).

3. R. P. Rumelt, “Good Strategy, Bad Strategy,” (Crown Business, New York, 2011).

4. D. Teece, “Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management: Organizing for Innovation and Growth” (Oxford University Press USA, 2009)

5. J. E. Ricart and J. Vilà, “Strategy and Levels of Strategy,” DGN 434-E, IESE Business School, 1991.

6. P. Cardona and C. Rey, “Management by Missions,” (Palgrave, New York, 2008).

7. I. Malbašić, C. Rey, V. Potočan. “Balanced Organizational Values: From Theory to Practice,” Journal of Business Ethics, June 2014.

8. R. Casadesus-Masanell and J. E. Ricart, “How to Design a Winning Business Model,” Harvard Business Review (January 2011), pp. 100-107.

9. R. Casadesus-Masanell and J. E. Ricart, “From Strategy to Business Models and Onto Tactics,” Long Range Planning, 43, 2-3 (2010), pp. 195-215.

10. R. Andreu, Huellas: Construyendo Valor desde la Empresa, Editorial Dau, Barcelona, 2014.