By Joseph Lampel, Ajay Bhalla & Pushkar P. Jha

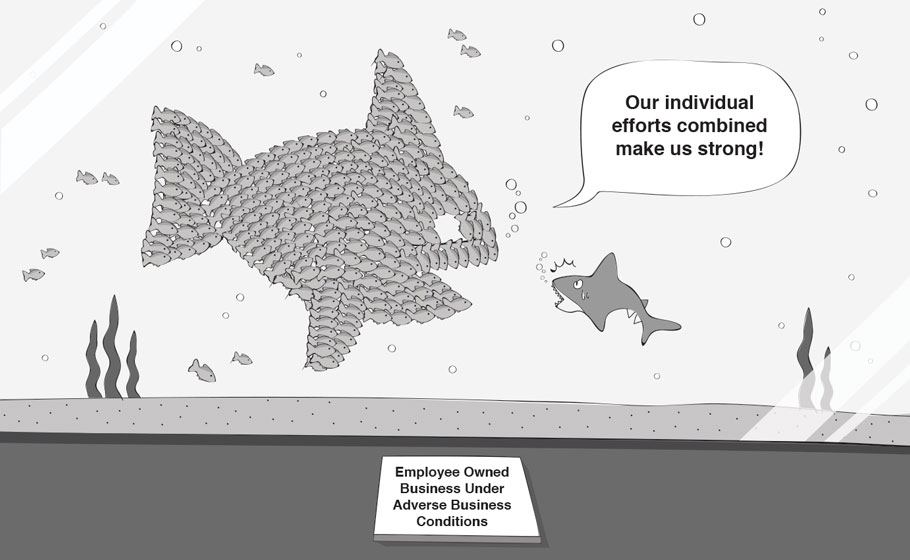

Criticism of modern corporate capitalism in the wake of the current economic crisis is reawakening interest in alternative ownership and governance models such as employee owned businesses (EOBs). EOBs are well suited for knowledge intensive firms where their combination of ownership and employee participation in decision-making fosters initiative and commitment. However, the relationship between ownership and employee participation that is central to the EOB advantage is potentially undermined by growth and complexity. This article reports on the results of a survey and archival study on UK-based EOBs that examines this issue. Taking advantage of the economic crisis, the study also examines EOB performance under adverse business conditions. Analysis of the archival data shows that EOBs lose their performance advantage over non-EOBs as they grow larger. EOBs, however, performed better over the entire business cycle, including the onset of the current economic crisis, demonstrating resilience and business sustainability relative to non-EOBs.

1.Introduction

A stream of corporate scandals followed by a financial crisis has ignited a debate on the potential pitfalls of modern corporate capitalism.1,2 In wake of this debate, increasing attention is being paid to ownership and governance models that represent an alternative to the publicly listed corporation. One model in particular is attracting renewed interest: Employee Owned Businesses (EOBs). EOBs have been part of the economic landscape since the industrial revolution. Until recently, however, they were viewed as an interesting governance model with certain advantages, but also with intrinsic limitations when compared to the growth and dynamism of publicly listed corporations.

One clear limitation to the employee owned business is built into the basic assumption that underpins this model: Employee ownership works best when employees feel a direct link between their efforts and the performance of the company.3,4 Success, however, often leads to growth, and growth can undermine the very advantage that often makes EOBs successful: As firms get larger, EOBs face the challenge of maintaining the link between employee efforts and firm performance that motivates employees to set aside narrow self-interest for the greater good of the firm.

We set out to study this issue in late 2008, just as the current economic crisis was beginning to take hold. Our study which was sponsored by John Lewis Partnership, the largest employee owned business in the UK, with support from the Employee Ownership Association (EOA), originally intended to look at the problems that employee owned businesses confronted as they scaled up their operations.5 However, in light of the economic crisis, we decided to add another dimension to the study which we felt was central to the merits of employee ownership when compared to other ownership and governance models: How resilient are EOBs? How do they fare in adverse economic environments when compared to non-EOBs?

To address these questions we surveyed 41 EOBs that are officially members of the Employee Ownership Association, and 22 non-EOBs. Our sample comprised firms across three sectors: manufacturing and processing, technical services, and professional services. The survey instrument was designed to contrast firm policies and performance in two time periods. The first, 2004 to 2008, a period during which the economy performed well, and 2008-2009, a period during which severe recession and the prospects of further economic deterioration was expected to change firm decision-making. In addition to collecting data on 41 EOBs and 22 non-EOBs via the survey, we also obtained data from the FAME database on employee numbers, profitability, and sales turnover. The FAME data covered 48 EOBs (41 that participated in the survey, and another 7 EOBs that declined to participate); and 178 non-EOBs. The 178 non-EOBs in this sample included the 22 non-EOBs that participated in the survey, and 156 non-EOBs that were not surveyed directly.

This article reports on the results of our study, and discusses their implications. In the first section we examine the scaling problem that EOBs confront when compared to non-EOBs. The second section uses performance related secondary data to examine the performance of EOBs when compared to non-EOBs prior to and during the current economic crisis. We conclude by emphasising some fundamental factors that underpin the promise of greater resilience from employee ownership. We discuss key issues that should guide strategic thinking when contemplating a switch to the Employee Ownership form – both at the firm and at the policy level.

2.EOBs vs. non-EOBs: Does scale make a difference?

Employee owned businesses have always exercised fascination for policy makers, researchers, and on occasion, entrepreneurs. Early interest was primarily motivated by the belief that economic justice is better served by firms where employees can take most, if not all, of the profits. This interest has waned as wages and benefits that accrue to employees have risen substantially. More recently, interest in employee owned businesses has focused on the ‘motivation problem’ that firms confront when seeking to foster in their employees the initiative and commitment that is crucial for creating new products, and delivering superior service.6,7 In a knowledge-based economy, so the argument goes, initiative and commitment cannot be enforced through contracts. For this reason, firms use a variety of incentive schemes to encourage employees to go beyond a narrow interpretation of their job description. A commonly used scheme is granting employees a degree of ownership by conferring stock options.8 Employee owned businesses go much further, allowing not only for ownership, but also giving employees voice in the management of the enterprise. In these circumstances, ownership and empowerment can combine to create an environment in which employee initiative and commitment increase substantially.

Research suggests that the effect is strongest at the small business and team unit level where employees’ sense of ownership is reinforced by easily perceived links between participation and outcome.9 The question in the present context is whether this increase is independent of organizational size. Put differently, does the EOB advantage decrease as firms become larger and more complex?

We approached this question from several perspectives. We first looked at the relationship between size and performance using the secondary data derived from FAME. We divided our sample of EOBs and non-EOBs into three sub-groups: firms with fewer than 75 employees, firms with 75-200 employees, and firms with more than 200 employees. We used two measures of performance: Profit before Interest and Taxes (PBIT), and profit before Interest and Taxes per employee (PBIT/employee). Our analysis shows that EOBs with fewer than 75 employees perform significantly better than non-EOBs with the same number of employees – performance measured as firm. This holds for the financial year ending 2005 and the financial year ending 2008. On the other hand, there was no significant difference in performance for EOBs and non-EOBs above this size. This suggests that in general, and irrespective of the economic conditions, as EOBs grow larger the employee ownership advantage diminishes. As a consequence, EOBs increasingly become, all other things being equal, similar in their organizational dynamics to non-EOBs.

This raises the question: Do EOB managers take steps to try and retain the EOB advantage? To address this question we split our survey sample of 41 EOBs and 22 non-EOBs into two parts. The first sub-sample comprised firms with less than 120 employees (small/medium firms) and the second sub-sample comprised firms with more than 120 employees (relatively large firms). We used the survey data to compare EOBs and non-EOBs in both size categories. Our results show consistent differences in managerial practices between EOBs and non-EOBs. For instance, EOBs and non-EOBs had similar attitude to the role of rules and procedures. By contrast, large EOBs put far less emphasis on procedures and rules than large non-EOBs. This points to managers of EOBs relying less on formal controls than non-EOBs of similar size. The most likely interpretation is ‘light touch’ supervision that relies less on formal controls and more on the motivation and commitment of employee-owners.

As organizations grow larger, they confront another common problem: failure of customer interfacing employees to pass crucial information further up the organization. An associated problem is the decreasing openness of top managers to ideas from employees who are more closely involved with customers and suppliers. Our survey data shows that small/medium EOBs and small/medium non-EOBs were similar when it came to seeking ideas from frontline staff, but that large EOBs were far more active than large non-EOBs in encouraging this pattern of communication. The evidence allows us to conclude that EOBs try to retain advantages of a closer link with employees even when they scale up.

Finally, we were curious if this behaviour was a function of performance. In other words, are managers in EOBs where employee commitment and initiative delivers superior performance more inclined to encourage practices that are likely to improve performance even further? To examine this question, we divided our sample of EOBs and non-EOBs into two groups according to profitability per employee. The first group consisted of all firms with more than the median value for increase in PBIT/employee, and the second of firms with less than, or equal, increase in median PBIT/employee. Our analysis of this data corroborated the above-mentioned findings: High profitability per employee EOBs were more likely to seek innovative ideas from staff. What our analysis also showed is that EOBs with high profitability per employee allow employees greater control over decisions that impact their daily routines than high profitability per employee non-EOBs. In effect, EOBs with high profitability per employee are more decentralized and grant employees more autonomy – a key feature of the relationship between top management and employees that is usually associated with greater flexibility and innovation.

3.Coping with Economic Crises: EOB performance under Adverse Business Conditions

In the last section we showed that employee ownership delivers strong advantage for small firms, but that this advantage tends to diminish as EOBs become larger. We also demonstrated that EOBs, particularly those characterised by superior performance, make efforts to retain these advantages. The economic crisis that emerged while we were planning our survey allowed us to address another question: How well do EOBs cope with adverse economic conditions relative to non-EOBs?

There are several factors that would lead us to predict that EOBs are better positioned to deal with economic crises, especially ones that follow rapid growth and expansion. The first is that EOBs are more constrained when it comes to raising capital for expanding operations. Second, employee owned firms are generally more selective when it comes to hiring, and more reluctant when it comes to firing. This reduces the incentive to expand operations simply to take advantage of growth opportunities, which as a result makes EOBs less vulnerable to downturns. From a more ‘micro’ perspective, greater commitment to the organization in EOBs encourages greater flexibility. Arguably, this should improve the ability of EOBs to adjust in the face of adverse economic conditions – employees are more willing to change their job descriptions, and display greater initiative when it comes to finding ways of cutting costs and improving customer relations.

With this in mind, we contrasted EOB vs. non-EOB performance along key indicators such as increase in sales turnover, increase in employee numbers, and profitability in two time periods: The first period of strong economic growth between 2005-2008, and the severe economic crisis between 2008-2009 during which business uncertainty peaked.

Our analysis showed that during the period of strong economic growth, non-EOBs recorded a higher average increase in sales revenue (12%) relative to EOBs (10%). During the crisis, however, EOBs outperformed non-EOBs with an average increase of 11% in sales revenue relative to just 0.6% for non-EOBs. What is interesting about our results is that they show a relatively stable rate of increase in sales per annum for EOBs over the combined two periods i.e. from 2005-2009. We find that it is the non-EOBs that go from 12% increase in sales revenue per annum in the pre-crisis period to less than 1% increase during the crisis period, indicating relatively greater susceptibility of non-EOBs to be adversely affected by economic downturns.

Another response to economic conditions is the willingness of firms to hire new employees. The willingness to hire is to some extent a measure of business optimism, but it is also a reflection of confidence in the long-term viability of the firm’s business model. Our data show that on the whole, EOBs tend to recruit more employees (measured as a percentage of total number of employees) than non-EOBs during both good and bad economic conditions. The difference between EOBs and non-EOBs increased markedly during the crisis – from EOBs hiring nearly twice as much during economic growth, to over four times as much as non-EOBs during the recession. In part, this is due to non-EOBs reducing employment, while by contrast EOBs actually increasing recruitment with the onset of the recession. This increase may be due to the greater availability of skilled employees when non-EOBs retrench. But it is also due to EOBs’ greater willingness to plan beyond current economic conditions.

Digging further into the data, we were interested in how sales performance and employment levels panned out at the level of the individual employee. We took sales turnover per employee as a proxy for productivity. On comparing EOBs with non-EOBs on this measure, we found that EOBs were significantly better in terms of productivity during the crisis relative to non-EOBs. During the growth period of 2005-2008, the difference between EOBs and non-EOBs was not significant.

We next turned our attention to profitability per employee. The difference between profitability per employee was not significant between EOBs and non-EOBs during the recession. Our analysis shows that, overall, EOBs have higher wage costs relative to non-EOBs. On a closer categorised analysis our data show that EOBs with wage costs of over £40k (~€50k) did better on overall profitability than their non-EOB counterparts, indicating that the higher wage costs of EOBs in the knowledge-intensive professional services sector are more than offset by the employee contribution to firm performance.

4.Conclusions

The current economic crisis has reawakened interest in employee owned businesses. The interest is in part due to distrust in contemporary corporate governance, and in part reflects discontent with the disparity between top management remuneration and stagnating salaries in the rest of the economy. Our study was originally conceived as an attempt to understand the limits of employee owned businesses, rather than champion their advantages. The onset of the economic crises allowed us to examine EOBs’ ability to cope with adverse economic conditions. What we found out was that EOBs represent a governance model that may be more sustainable than firms that are investor owned or publicly listed.

At the same time, we also found that as EOBs grow larger and more complex they tend to lose the employee ownership advantage. In other words, the commitment and initiative taking of employees in EOBs becomes harder to maintain as the number of layers that separate first-line employees from top decision-makers increase. Enlightened management can work to counter this tendency by delegating greater decision-making powers, and by reducing formal controls to a minimum.

Even when EOB managers take steps to ensure that the employee ownership advantage is retained, the fact remains that employee ownership alone is not a guarantee of success. Employee ownership is only one part of a configuration that combines to deliver superior performance. Many other factors such as good strategic management, willingness to make tough product and market decisions, access to capital when it is needed, play an important role.

More to the point, it became apparent when talking to EOB managers that successfully managing EOBs requires awareness that many other aspects of management and decision-making have to fit together in this context for the EOB

advantage to become sustainable. The difficulty of achieving this fit, especially as EOBs grow bigger, may account for the fact that EOBs currently account for a relatively small percentage of economic activity. Our study, however, provides evidence that this percentage will likely grow as our economy becomes reliant on knowledge intensive firms where employee commitment and initiative is crucial for performance.

About the Authors

Joseph Lampel is Professor in Strategy and Innovation at Cass Business School. His current research explores (a) impact of ownership structure on strategic decision-making and performance in employee-owned business (b) how organizations boost creativity under constraints, and (c) how organizations learn through rare events. He is the author with Henry Mintzberg and Bruce Ahlstrand of the one of the best selling strategy books: “Strategy Safari“, Free Press, and has published in top journals such as Strategic Management Journal, Organization Science, Journal of Management, Journal of Management Studies and Sloan Management Review.

Ajay Bhalla is Professor of Global Innovation Management at Cass Business School. He has specific research interest in (a) How Ownership & Governance Structure influences strategic decision making, with specific focus on Employee Owned and Family Businesses, and (b) What makes firms innovate better and what are the implications of pursuing innovation across boundaries for firm configuration. He has published in journals such as Academy of Management Perspectives, Journal of Operations Management, and Journal of World Business.

Pushkar P. Jha is a lecturer in strategy at the Newcastle University Business School. He has contributed to leading journals like Academy of Management Perspectives and International Journal of Project Management. He has also published in practitioner-oriented books like the Project Management Handbook of Knowledge and the Evolution of Business Knowledge. He has a keen interest in the areas of project-based learning, innovation and employee ownership models. The interest stems from his work on design and monitoring studies on cooperatives and enterprise development in some major funding initiatives of the World Bank and the UNFPA.

References

1.Kruse, D., R .Freeman and J. Blasi (2010) Shared Capitalism at Work: Employee Ownership, Profit and Gain Sharing and Broad Based Stock Options, Chicago and Cambridge, MA: University of Chicago Press and National Bureau of Economic Research.

2.Gilbert, Ronald J, Dickson, Buxton, C, Bryan, Golden, J, and Paige, Ryan, A (2009). “Navigating through Tough Times with the Aid of Employee Ownership: How ESOPs and/or MSOPs Can Become Viable Economic Allies”. Journal of Financial Service Professionals. 63 (4): 57-66.

3.Kramer, Brent (2010). “Employee ownership and participation effects on outcomes in firms majority employee-owned through employee stock ownership plans in the US”. Economic & Industrial Democracy. 31 (4): 449-476.

4.Bartram, P. (2012). “What about the workers”. Financial Management, 26-30.

5.Lampel, Joseph, Ajay Bhalla and Pushkar Jha (2010)“Model Growth: Do Employee-Owned Businesses deliver sustainable performance?” www.employeeownership.co.uk/download/MTE3

6.Sauser, William (2009) “Sustaining Employee Owned Companies: Seven Recommendations”. Journal of Business Ethics, 84 (2): pp. 151-164.

7. Blasi, Jospeh. R., and Kruse, Douglas L. (2010). “Shared Capitalism at Work: Employee Ownership, Profit and Gain Sharing, and Broad-Based Stock Options”. Journal of Employee Ownership Law & Finance. 22 (3): 43-79.

8.Oyer, Paul and Scott Schaefer. 2005. “Why Do Some Firms Give Stock Options to All Employees? An Empirical Examination of Alternative Theories”. Journal of Financial Economics 76(1): 99-103.

9.Bayo-Moriones, Alberto and Martin Larraza-Kintana (2009). “Profit-sharing plans and affective commitment: Does the context matter?”. Human Resource Management, 48 (2), p207-226.

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-100x70.jpg)